TOGETHER ALONE

New Zealand’s silent Pasifika mental health crisis

What do you do if your culture treats mental illness like a curse? Bury it deep. Indira Stewart reports on why so many Pasifika people suffer psychological distress - and why so few seek help.

Warning: This story discusses suicide, sexual violence and family violence.

The carport where Naylar Uisa almost died is made from pieces of old wood nailed together, and a tarpaulin draped over the front. Tucked in between two state houses, it sits at the end of a long driveway in one of South Auckland’s poorest suburbs.

The bell at a nearby primary school rings and the sound of children laughing carries on the wind. A young boy on a bike does wheelies up and down the street and yells out “Otara hard!” as he passes by.

Naylar, 32, went to a tangi this morning so is dressed in black as she pads around the carport, her flat slip-on shoes making soft sounds on the concrete. She waves toward the state house to the right. “This is my foster home where a lot of my suicide attempts happened,” she says. She looks up at the rotting wood on the roof of the carport. “And this is the carport where I tried to commit suicide.”

She draws back the ripped tarpaulin, exposing a suede sofa, its brown fabric worn and faded. An armchair nearby has the foam padding ripped out of its arms. A pair of worn-out shoes lie on the concrete floor and a broken bike leans against a rickety table.

Naylar was 12 years old when a CYFS social worker walked her up the long driveway, and she looked up at the carport and adjoining house for the first time. She clutched a plastic supermarket bag that contained her only belongings - a jumper and a pair of trousers. She had been through more than 30 foster homes in the preceding three years, and had felt suicidal during much of it.

The day she tried to end her life in the breezy Otara carport was not the first or last time she would attempt suicide.

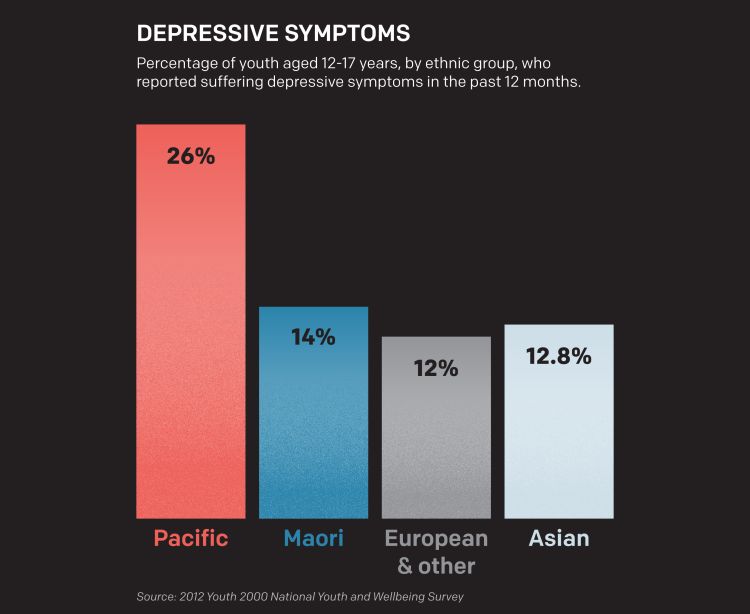

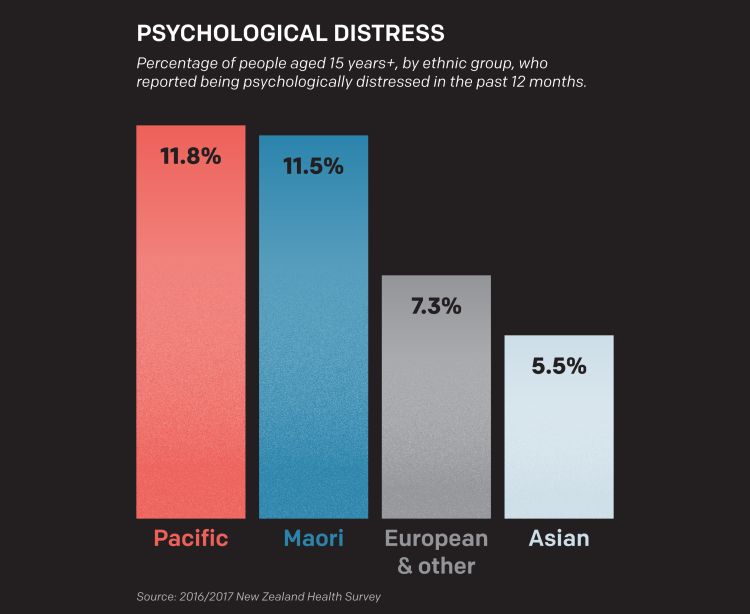

The depression Naylar experienced growing up is startlingly common among Pacific people living in New Zealand: they have higher rates of psychological distress than any other ethnic group in the country, Ministry of Health figures show.

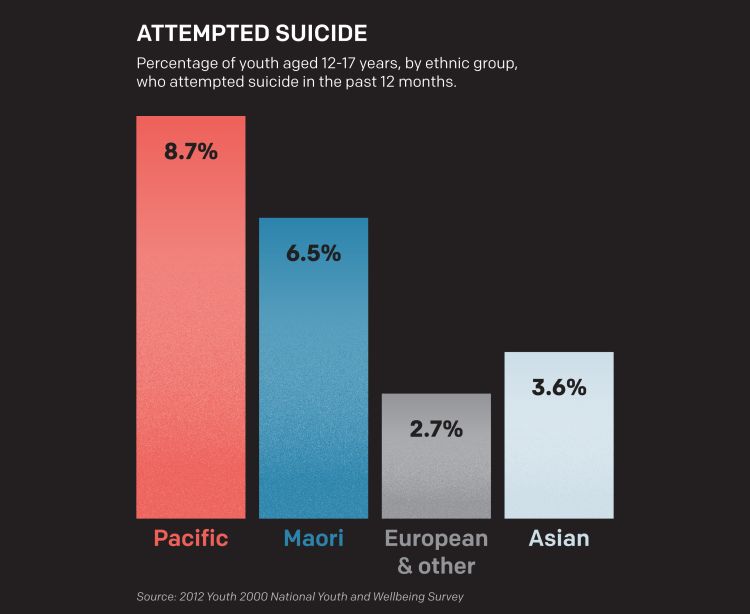

Delve into youth statistics and the picture becomes darker. The Youth ‘12 study of students in years 9 to 13 found Pacific youth reported higher rates of depressive symptoms and suicide attempts than any other ethnic group, and more than half of them had intentionally self-harmed in the past 12 months.

In New Zealand overall, suicide is most prevalent among people over 40, but for Pasifika, it’s most common in 15-24 years olds, a 2017 study showed. Pacific health and well-being organisation Le Va says suicide is the leading cause of death for Pacific teens.

But despite this, Pacific people access mental health services at much lower rates than other New Zealanders, according to government reports.

The statistics are confronting for Pasifika, and they immediately raise the question - why?

The New Zealand Mental Health Foundation says risk factors for mental disorder and suicide include physical and sexual abuse, socioeconomic deprivation,and ongoing conflict - including spiritual and cultural. Other factors are having experienced loss - including the loss of a relationship or a job, and being aged 16 to 24.

Line these factors up alongside statistics about Pacific people’s lives and answers to the high rates of psychological distress begin to emerge. About half the Pacific population is under the age of 25, and they have the highest unemployment figures and lowest household net worth of any other ethnic groups.

The Youth ‘12 study found 71 percent of Pacific youth lived in poor neighbourhoods, 20 percent lived in overcrowded housing, and 22 percent had experienced sexual abuse or coercion. A quarter said their parents worried about having enough food, and a third had witnessed physical abuse by adults towards children in their home. The rates were significantly higher than youth from other ethnic groups.

The statistics are disturbing, but the reality of what they represent far more so. Ask Naylar.

“I was a product of rape when my mother was only 16,” she says, pressing her hand against the wooden frame of the carport. “Because of that my grandparents raised me in Samoa. I grew up thinking that they were actually my parents.”

At 8, Naylar was flown to New Zealand to live with her “older sister” and her husband and their kids. “That’s when they told me she was actually my mother. It was a real shock for me as a child realising my parents were actually my grandparents, my brother was actually my uncle and my sister was actually my mother.”

“With Pacific families it’s quite hard to deal with someone that’s pregnant at a young age. So they shamed her. I just got the harsh part of it. So everyday with my birth mother she will say stuff like, ‘I should’ve killed you before you were born’, or, ‘I wish that you were never born because my life was miserable.’”

Naylar says she was strangled with a jug cord, held underwater in the bath, and sexually abused while living with her family. Her CYFS records contain notes about school staff reporting Naylar being covered in bruises. When questioned at school, Naylar says, she would lie to protect her family and her mother would remove her from the school and enroll her in a new one.

But her breaking point came when she was beaten by her uncle, who thought she’d taken a chocolate bar he had left in the fridge. She walked, her face covered in blood, to school and headed straight to the counsellor’s office to ask for help.

“I remember it was so embarrassing, because the bell had already gone and all the kids were walking home and they could see me all messed up with blood everywhere. But I was just desperate for help.”

CYFS removed her from her mother’s care.

But shifting from foster home to foster home did more damage: she was neglected and sexually abused. Her CYFS file contains notes made by social workers describing her as “distressed and anxious” and worrying she was suicidal.

“I was always anxious and I found it hard to be around people because, you know, I just didn’t know how to do connection. I just remember I felt sad all the time and even when you’re in a room full of other people, you feel so lonely.”

“At one house, me and the other foster kids were always made to eat outside while the family and their real kids would sit at the table and eat inside. It was always like that so you carry on with life feeling like you’re not wanted. Most of the time you cry at night because, you know, you still don’t feel like you belong to anybody.”

In her cluttered Auckland home, Dr Karlo Mila sits at an oak dining table flicking through paperwork. Reports are strewn across her frangipani-patterned table runner and a bookshelf nearby is packed with volumes celebrating the mana of Pacific people.

Dr Mila has worked in the area of Pacific health, research and policy for 15 years. She wrote the Pacific report for the government’s recent mental health inquiry.

“The state of play isn’t great and it’s very well evidenced that the New Zealand-born Pacific population carries the burden of poor mental health,” she says, pointing to Te Rau Hinengaro - a 2006 study that was one of the first to reveal Pacific people were most at risk of mental distress.

For her PhD, Dr Mila explored which factors were protective against suicide for young Pacific people. Among the 1000 New Zealand-born Pacific people she surveyed, those who didn’t feel accepted by their own community were most at risk of attempting suicide.

“What I also found was that less than half of our Pacific people born here in New Zealand actually did feel accepted by members of their own culture and by others, which is a little bit damning,” she says. “It kind of suggests that on some level it’s not exactly a super-positive environment to grow up in.”

What’s interesting, she adds, is that despite the high rate of suffering among Pacific people, the concept of depression was non-existent until recently. “It’s very new to have mental health symptoms institutionalised or medicalised, and we have a lack of comfort with all kinds of institutions here. I mean they’re very palangi structures.”

Back in Otara, sitting in front of a broken trampoline in the backyard of her old foster home, Naylar confirms she didn’t know what depression was. “I just didn't know it was an issue. I didn’t even know that there was like, a word for it, you know. I just thought it was normal and that I’m the dumb one that didn’t know how to deal with it. And so that’s why I just never really thought that it was something that I needed to get help for.”

‘Amanaki-Lelei Prescott, 29, pulls into the carpark on the summit of Mount Roskill, a place she often comes to when she needs to escape.

It’s not the view over to Mt Albert, with its flurry of trees, or the feeling of being up high that provides comfort but the act of sitting in her car.

“My car to me is my sanctuary, it’s my safe haven,” she says as she gets out to sit down on the grass beside it.

“I go through these times and I’m just so low, I feel so sad and it’s like heavy. And it makes me not want to do anything or be around anyone. I just know that no one will understand so I end up pushing people away - especially those who are important to me. So I hop into my car and lock the doors and just drive off.”

The wind tussles her long, straight hair as she describes how depression feels like being on a rollercoaster; some weeks she feels good, some weeks she feels low. Very low. “I’ve attempted suicide like…” She pauses and stares off into space like she’s trying to count, before giving up. “Oh, I don’t know how many times I’ve tried to see Jesus early!” She laughs but it’s an uncomfortable laugh.

She’s grabbed a Minnie Mouse soft toy from the backseat of her car and she clutches it tightly.

“The first time I attempted suicide, all I remember is that day, I didn’t go to school and I just lay on my bed and cried and cried hardout, like I couldn’t stop crying, I couldn’t control it.”

‘Amanaki’s experience is in line with the statistics on Pacific people and psychological distress: despite her illness becoming frequently life-threatening, she has never sought professional help. “I just don’t want to burden anyone,” she says.

But it’s more than that. She’s absorbed the message that she should stay silent, that she should keep her distress to herself.

When she first attempted suicide at the age of 15, one of her sisters helped save her life. Her sister has never spoken about it with her since, she says. Nor has anyone else in her family.

Years later, she was hospitalised following another suicide attempt. Her family visited and there was some discussion about how ‘Amanaki had been feeling and what had happened, she says. But after they left, she received a phone call from her brother. “He said that Mum and Dad had told him that I was just being silly and that I was too old to have thoughts like that. And you know, that just confirmed to me that I will never have this conversation with them. I will never talk to them about feeling depressed or suicidal. Because they just wouldn’t get it.”

‘As Pacific Islanders we’re always told, ‘You know what happens at home stays at home’. You don’t take your drama out, you don’t go talk about it. No one would want to communicate or express their feelings. Especially if you’re being mocked about it. Like, your feelings are your own feelings, you can’t help if you feel that way, but people just don’t get it and it’s such a joke to them. Especially Pacific Islanders. It’s because they don’t believe in mental health. They believe in getting hidings.”

‘Amanaki is frustrated now. She flicks back her hair impatiently. “At home, it’s religion and church, you have to be this, you have to do that. As Pacific Islanders we’re so like, ridden on religion...and religion!”

She, like many Pasifika people, has an unwavering Christian faith (“I always talk to God. I always ask him, you know - 'Am I ok?'”), but the church’s silence over the mental illness affecting so many Pacific Islanders angers her. “You see the minister stand in front of the church and talk about this and that. But no one ever talks about suicide. No one ever talks about depression. Why don’t they ever preach it from the pulpit?”

'AMANAKI

"The first time I heard the word faggot"

‘Amanaki-Lelei was born into a devoutly religious Tongan family, the fifth of 14 children in the house. Her childhood was difficult; she identified as a girl but her family initially struggled to accept her as one.

"The first time I heard the word faggot was when my brother called me it. I always thought it was just someone who was fat only because of the letter 'f’. And it wasn't until I started hearing it more frequently that I realised what that word meant. So I never thought I could talk to my brother and I just had no friends in primary that I could express myself around."

Her family tried to make her more masculine. "If I got up and walked out of the room, my dad or my uncle would say, 'Come back and do it again'. So I'd have to come back and repeat it and they would be like "Again… and again… again..." and I'd just have to keep on doing it until they were happy. This was like, every day - they were trying to fix me."

Transgender people are vulnerable to mental illness. The Youth ‘12 found about 40 percent of teenagers who identify as transgender have depression and nearly half of transgender respondents had self harmed in the previous 12 months, while 20 percent had attempted suicide.

Hormone therapy has helped ‘Amanaki feel better about herself as a woman, but it’s a double-edged sword: the treatment can exacerbate depression. Following a suicide attempt, medical staff told ‘Amanaki they would take her off the hormones."I just told the nurse, 'Please don't do this to me! You can't do this to me!,' I was desperate. It's like taking away everything I am. Taking it away will just make my depression worse.

“There are times when I know it's making me feel low so I'll hop off for a couple of weeks just to be safe. But after a while I can feel my body changing and it's disgusting and I can't handle it, so I hop back on."

As an award-winning performer, ‘Amanaki has found the freedom to be herself through theatre. “Theatre gave me the tools to be on stage, in front of people and get to finally tell them how I feel or the story of whatever I want to say.”

“It’s fun, and I think it really helps.”

In a quiet street on Auckland’s North Shore, the doors of an old wooden church are wide open and the amplified, booming voice of Reverend Tevita Finau can be heard by the palangi locals drinking coffee outside the cafe across the road. “Mau fakamālō mo fakafeta’i ki he ‘Otua ‘oku ne foaki mai mo’ui!” (“We give thanks and praise to God who has given us life!”)

The perimeters outside are decorated in fading Tongan flags, the pews inside are filled with Tongan methodists - the older among the congregation are focused on the Reverend, the younger seem uninterested. “‘I he taimi faingata’a, hanga hake ki he ‘Otua!” (“In hard times, look to God!”), Rev Finau continues.

It’s a timely sermon; there have been a number of suicides recently amongst the Tongan church community.

Rev Finau, the National Superintendent of the Tongan Methodist church, is one of very few Pacific church leaders who will talk openly about mental health. He says the suicides have been “challenging for the church”. “Some were not well prepared and congregations were struggling and also church leaders were struggling as well,” he says.

Pacific elders struggle to grasp the concept of depression; the communal village life they grew up in did not allow for people to be lonely or depressed, he says. “When I grew up in Tonga there were no talks of depression. There was talk of people exhausted, and fatigued. But there was no talk of depression that I could recall.”

“Most of the parents grew up overseas in Tonga… And some of them are struggling to make changes and to be able to listen more to the kids and to be able to recognise signs of when young people are unhappy. A lot of [our elders] are still learning and of course a lot will not unlearn what they’ve grown up with… but they need to learn more about depression and also being stressful here, being lonely.

He’s aware the language used to describe mental illness can stigmatise those experiencing it. “People use words like ‘vale’ or ‘fakasesēle’ (stupid, crazy, deranged). But also mainly they explain it as ‘puke fakatēvolo’ - devil sickness. That explains why people are struggling, because that’s how they are trying to give an explanation as to why someone is going through a mental health experience.”

The suicides have been a wake-up call, Rev Finau says. “It concerns us very much. It’s something that we are worrying about and not only praying for solutions but we are actually working on that.”

Some older church leaders and members of the congregation interpreted the suicides as inevitable. “Some of them thought it’s the will of God. But we had to work - God does not want anyone to take the life of anyone else or his or her own life, you know, to bring harm to himself or herself.”

His own words about suicide then veer into familiar Christian territory: “It’s not good and it’s very wrong - morally wrong,” he says. “It’s ungodly.”

While religion is strongly embedded in Pacific culture, using religious language to describe mental illness is problematic, says Dr Karlo Mila. She leans forward in her dining room chair and rests her forearms on the table. “Christianity has turned that (mental illness) into ‘Puke tēvolo’ or a curse. Actually, even just the idea of a curse is very unhelpful. So you rock up as a Tongan person and try and explain to the mental health practitioner that it’s a curse and they see that as incredibly unhelpful,” she says.

The relationship between church and mental health in the Pacific community is a very complicated one that needs a lot of unpacking, she says. “There aren’t consistent messages. We’ve all heard the stories about young people taking their lives in churches and you know, that’s devastating.”

JAY

"My family’s reaction was ‘Cover it up’”

Niuean Dad Jay Williams sits at a McDonald’s in West Auckland, enjoying a chicken wrap. He spent five years battling mental health problems, including drug-induced psychosis, after abusing painkillers and other medications.

“When I first reached out for help - my family’s reaction was ‘Cover it up’,” he says. He beat the odds by forging ahead and asking for professional help, but quickly figured out one reason why other Pacific people don’t: confidentiality issues. The professional he saw told one of his relatives, who worked in the health sector. His relatives then accessed his records and confronted him. “The breach of privacy - it nearly destroyed me,” he says.

It didn’t end there. During one of Jay’s appointments, a relative burst in and asked him what he was doing there.

Jay’s experience was not an isolated incident. Dr Mila says because the Pacific community is small, confidentiality can be compromised when accessing Pacific health services where other Pacific people work. Plus, in cultures where elders can feel it’s their right to know what’s going on with younger members of the family, they may deliberately breach confidentiality, like Jay’s relatives did.

Pacific people can also be put off accessing help if they have a history of experiencing institutional racism, says Dr Mila. “When you’re in mental health crisis, you tend to be feeling the most vulnerable and desperate that you’ve ever felt before. So to engage with an institution where you don’t understand how it works is kind of frightening and [especially] if you’ve had poor experiences of other institutions like Immigration.”

Indeed, the government's mental health inquiry report, released last week, said Pasifika reported the current system wasn't working for them and was intimidating. "Consistently, Pacific peoples spoke of a lack of quality and described services they found hostile, coercive, culturally incompetent, individualistic, cold and clinical. We heard many times of their experiences of pain, inequity, institutional racism and preventable loss."

Pasifika, the report said, were calling for the adoption of "Pacific ways". "What we heard was a need for an extended village of Pacific services working cooperatively and collaboratively, with complete cultural integrity to adequately meet the needs of Pacific peoples."

Jay didn't get that when he sought help, but - even considering the interference from his relatives - he doesn’t regret going to the professionals. He received wrap-around support services which helped him in his recovery. It also changed his ideas about what Pacific people experiencing mental illness need.

Before his breakdown, he worked as a national suicide prevention coordinator working with Pacific youth. Now, having experienced mental illness himself, he thinks the way he was operating was not always helpful. “I realise a lot needs to change. There is so much on policy but real stories need to be part of the conversation. Even though talking about it is the hardest first step, every story is important and represents the picture of our community.”

Jay’s dream is slowly creeping toward reality. Over the past 10 months, public consultations were held all over the country as part of the government’s mental health inquiry. They were led by a six-member panel, two of whom were Pacific people. The panel met with thousands of people, including people with lived experience, their family members family, service providers and community groups. It was the first time Pacific people had been offered the opportunity to share their experience to a national board.

And they did share: difficult stories about experiencing mental illness; heartbreaking stories of losing loved ones to suicide. But what came through the most was a fear the problem was growing and a desperation to tackle it.

Naylar walks around her old foster home and stops by a grapefruit tree."We used to have war games with the neighbourhood kids. And we would always win because we had the big grapefruits while on the other side they just had the small feijoas,” she laughs.

It was in this home, that Naylar found the connection that would help her begin healing. The day she attempted suicide in the carport, her foster mother, Sybil Bunyan, who she calls “Mum”, swung her noisy red Honda Prelude into the driveway just in time to save Naylar’s life. She grabbed her, hugged her tightly and told her over and over again, “You’re my girl”.

“It’s a hug I’ll never forget,” says Naylar.

Her “Mum” cared for her for the rest of her childhood. She passed away ten years ago, but her impact on Naylar’s life remains. "I call her my 'Unpacker' because she helped me unpack all of my hurt,” she says. “I miss her, but I'm just so grateful for everything that she had taught me. I feel so grateful that I had someone to unpack my hurt and actually put a word to it."

Naylar says her “Mum” would often take her for long drives and tell her all the great things she believed Naylar was going to do with her life.

Today, she is married with four children - two are her biological children and two are children she fosters. "I love that I get to do things together with them. Everything that I never got to do as a child, I get to do that with all of my children.”

She’s followed her “Mum” and her mission in life now, she says, is to help others heal from pain. She founded an organisation called Reaching Out to support disadvantaged people in Auckland, and has won multiple awards for her work in the community.

“It’s what I feel like I'm built for,” Naylar says. "Seeing my past, yes, I was ashamed of it. But now it's more of my drive. It's helped me do more. If I see someone struggling, I'm not going to let you bleed. I'm going to come and help you.”

It’s a life she never imagined she would lead. “Before coming to Mum's, I honestly never thought that I'd be where I am today. Because I just never saw my future."

Executive Editor Veronica Schmidt

Pictures of Jay Williams by Derek Henderson. All other pictures by Stephen Langdon

Videography and video editing Tim Collins

Graphic Design & Data Visualisation Scott Austin

Art Direction Dave Wright

Made possible by the RNZ/NZ On Air Innovation Fund, the Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand and Frozen Funds Charitable Trust.

Where to get help:

Mental Health

Need to Talk? Free call or text 1737 any time to speak to a trained counsellor, for any reason.

Lifeline: 0800 543 354 or text HELP to 4357

Suicide Crisis Helpline: 0508 828 865 / 0508 TAUTOKO (24/7). This is a service for people who may be thinking about suicide, or those who are concerned about family or friends.

Depression Helpline: 0800 111 757 (24/7)

Samaritans: 0800 726 666 (24/7)

Youthline: 0800 376 633 (24/7) or free text 234 (8am-12am), or email talk@youthline.co.nz

What's Up: Online chat (3pm-10pm) or 0800 WHATSUP / 0800 9428 787 Helpline (12pm-10pm weekdays, 3pm-11pm weekends) Kidsline (ages 5-18): 0800 543 754 (24/7)

Kidsline (ages 5-18): 0800 543 754 (24/7)

Rural Support Trust Helpline: 0800 787 254

Healthline: 0800 611 116

Rainbow Youth: (09) 376 4155

If it is an emergency and you feel like you or someone else is at risk, call 111.

Sexual Violence

Victim Support: 0800 842 846

Rape Crisis: 0800 88 33 00

HELP: Call 24/7 (Auckland): 09 623 1700, (Wellington): be 04 801 6655 - 0

Family Violence

Women's Refuge: 0800 733 843

It's Not OK: 0800 456 450

Shine: 0508 744 633

Victim Support: 0800 650 654

HELP: Call 24/7 (Auckland): 09 623 1700, (Wellington): be 04 801 6655 - 0

Other

Eating Disorders Association of NZ: 0800 233 269

Abuse Survivors

For male survivors:

Road Forward Trust, Wellington, contact Richard: 021 1181043

Better Blokes Auckland, 09 9902553

The Canterbury Men's Centre, 03 3776747

The Male Room, Nelson 03 5480403

Male Survivors, Waikato 07 8584112

Male Survivors, Otago 021 1064598

For female survivors:

Help Wellington: 04 8016655

Help, Auckland: 09 623 1296

For urgent help: Safe To Talk 0800044334

If it is an emergency and you feel like you or someone else is at risk, call 111.