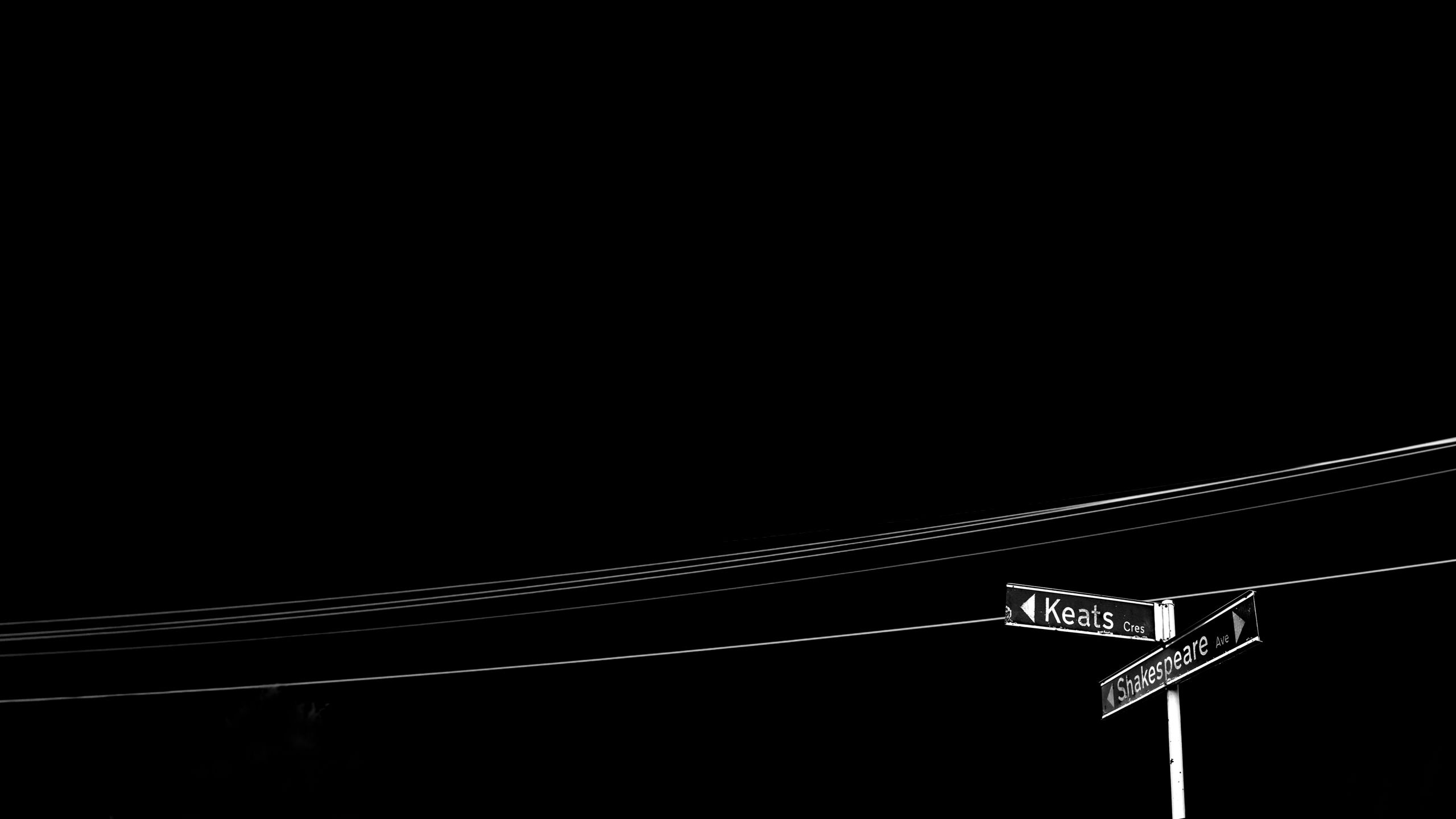

It’s one of the poorest neighbourhoods in the country, and has been for 60 years. Yet stalwarts of the suburb won’t ever give up trying to improve the lot of ‘The Hood’.

Max Towle reports.

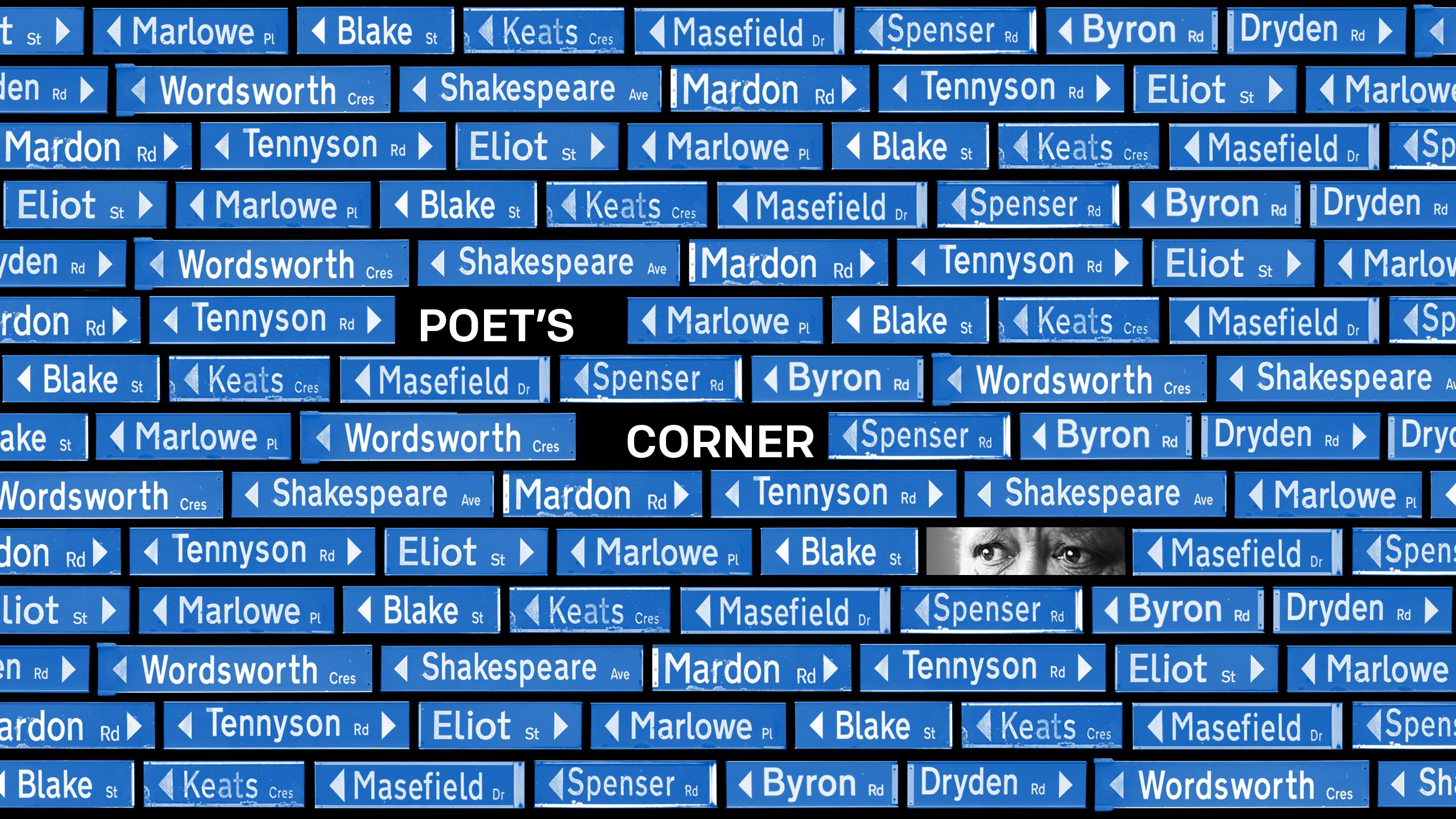

Down Mardon Road and around Shakespeare Avenue and just beyond the corner of Keats Crescent, in a white weatherboard house, Annie Williams sits at her kitchen table having a smoke. From her window she has a perfect view of her street.

This morning, she is distracted by a puppy that has escaped her neighbours’ backyard via the underside of their house and is ambling along the tarmac. She tells her grandson, Arctic, to go over and shepherd the dog back and pile up punga so it can’t escape again, but it does.

She drops her ash in a small glass dish. There are artefacts and shells on the windowsill and pots and pans in the sink. Behind the door is flax and taonga from a Māori craft store she ran a generation ago.

She grabs a handful of curtain and laughs. “Get a shot of these in your camera, then Housing Corp will have to get me new ones.”

She has lived in Enderley for close to 50 years. The suburb of Hamilton is better known as Poet’s Corner because the streets are named after classical British poets.

She is Poet’s Corner’s wahine toa. She knows everyone, and everyone knows her. Every year, members of the Mongrel Mob bring her a Christmas hamper. Visitors walk in unannounced, sometimes just to sit at her table and kōrero.

She tells stories about Poet’s Corner. There was 1994, when the then-mayor of Hamilton compared the suburb to a slum. She remembers a marae that was proposed but never built.

When Annie first moved to Enderley it was “real papakāinga living”. Her cousins and aunties and uncles lived nearby, and it felt like her childhood. “You used to have the marae there, the dining room, the chapel and the whānau all living on one site.”

Over the years, they moved on. Six of her nine children now live in Australia. They left for a better life. “They started going away because it was poor living. They didn’t want to raise their kids in this situation, and they were right. That’s the beauty of the young generation, they can vision ahead and they didn’t want to raise their kids in poverty.”

Just to the east of Poet’s Corner there are expansive construction sites. Within a couple of years, a new $2.1 billion four-lane expressway will connect Hamilton with the Bombay Hills, while dozens of new offices in the Waikato Innovation Park will solidify the region as the country's fastest-growing technology sector. In the next couple of decades, a $3.3bn inland port will create about 11,000 new jobs.

Across the whole of the city, about 1000 homes are under construction. The spread north is happening in Horsham Downs and Sylvester, where new developments are constantly springing up, while about 1800 new properties will go in near the inland port.

As New Zealand's population is nearing 5 million, Hamilton’s is growing too, and is expected to rise from 170,000 to 300,000 within the next 50 years. Some believe it could reach a million.

Yet cross Wairere Drive, which borders Enderley, and there is a sense that Poet’s Corner has been left behind.

There are empty decaying homes, and overgrown sections where two-storey state houses were demolished more than a decade ago.

On Mardon Road, which runs through Poet’s Corner like a blood vessel dividing the suburb, a row of shops show the wear of time and neglect. There is a self-service laundromat and a food mart where the prices of toilet rolls, sugar, and Mountain Dew are spray-painted on boarded-up windows like graffiti. Between these stores, locked-up roller doors hide vacant spaces.

“I’m sure we see the end of the purse,” Annie says. “Or, does the purse even get here? It’s getting more and more obvious when you don’t see any work getting done.”

Enderley was created and its streets named by the city council in 1959, and it quickly amassed one of the largest concentrations of state housing in the country.

Now, there are only a handful of newer developments that differ from the older, smaller wooden homes. In 2014, a massive housing complex of 62 new units was proposed for Shakespeare Avenue. Only eight have been completed.

Raymond Bird, a businessman whose family trust owns much of the shopping area at the southern point of Enderley - the Five Cross Roads - says developers are apprehensive when there are bigger profits to be made elsewhere in Hamilton. The stigma of Poet’s Corner doesn’t help, either.

“The difference between Fifth Avenue (which borders Enderley) and Tennyson Road is massive,” he says. “Fifth Ave is only one road away, but a house there would probably command about $100,000 more.”

Poet’s Corner has never been able to shake its reputation for crime.

The suburb has historically been a Mongrel Mob stronghold, and patches are still visible. Famously, in 2007, the post office refused to deliver to Enderley for a few days after a gang shootout.

Annie remembers it slightly differently. “Oh, someone had a gun and was shooting randomly on Shakespeare Ave. The poor old postie wouldn’t come back for a long time,” she chuckles. “Well, I wouldn’t blame the postie, would you?

“You would get so many police cars rolling through, and when they did an arrest there would be so many of them and they’d always make a big scene. Everyone here would rush to that spot, especially the kids.”

In 2011, when the police began setting up its first neighbourhood policing teams in “priority areas” in New Zealand, Enderley was singled out. Few officers put up their hands. Sergeant Craig Taylor cautiously accepted the responsibility.

He had already worked in Hamilton for more than a decade, starting when streets like Tennyson and Wordsworth were synonymous with fights and stabbings. “Real Once Were Warriors country,” he says.

Tennyson Road

Tennyson Road

He and a team of five set up an office in the community centre, and over a few months, knocked on about 500 doors. “At the time, for us the biggest issues in the area were burglaries and domestic violence, but for the community, it was stray dogs.”

He remembers one family - “an entrenched crime family” - he endeavored to help. The matriarch was a grandmother who had been involved in gang life since she was 14. Her three adult children were patched, and there were five teenagers who were prospecting. Along with 10 more children under the age of 11, they all lived in the same three-bedroom state home. Many slept in the garage.

He says by spending time with the grandmother - rather than banging down the door and leading people away in handcuffs - he saw her attitude, and that of her family, begin to change.

Sergeant Craig Taylor

Sergeant Craig Taylor

“Locking people up is a consequence, not a tool of change,” he says. “People were very guarded when we arrived, but that was as much about survival.”

He says working in Poet’s Corner humbled him. “Everyone has their own story, and until you’re willing to listen … you’ll never realise we’re all the same, some of us are just living in different circumstances.”

When things appear to be going well in a tightly knit suburb like Enderley, he says the good spreads as easily as the bad. When things go badly, everyone “closes up shop.”

The sergeant has now returned to the front line, but violence has not left Enderley.

About a year ago, while her son studied in the front room, Alvina Edwards heard a gentle rapping on her door and opened it to see a camouflaged man holding up a rifle. He pressed its muzzle to her head and pulled the trigger. The gun clicked, and she slammed the door. For a moment, she believed she was about to die in front of her son.

She still does not know why. Perhaps a scare thing, or a wrong address. She says the officer who later came to her home told her, “You should have had a peephole.” So now she does.

“As hard as you try, you can’t help but be reminded of what people have to go through - what you have to go through - until it comes to your front door,” she says.

Alvina has lived in Enderley for about 20 years and is a Māori mentor at Waikato University. In another corner of her living room is a desk cluttered with research for her doctorate - she already has a Masters of Laws.

“I got addicted to education because I wanted to show my children that they had to finish school and go to university or learn a trade, so they can get out of this,” she says.

While working at the community house, she remembers rushing over to help a 6-year-old girl who had been clipped by a car. She urged the girl’s family to call the police. “They wouldn’t because they were worried that they would be the ones arrested.”

Alvina says cops used to turn up and simply say, “Back of the car.”

“I know I distrust cops, but I suppose it’s just because I hate the system, and the way the system has historically been enforced on our people.”

Walking into Alvina’s home on Enderley Avenue, you are immediately struck by the smell of an incense candle burning in the corner - her “death corner,” where photos of family members hang on the wall and rest on a small, wooden table beneath an ethereal painting. “I have angels watching over them,” she says.

Alvina says crime and poverty are inter-generational. “That trauma has to stop at some point.”

While working at the community house, she remembers meeting old people who were sick, or mums without power, or children without food, or people living with domestic violence.

She says the poverty in Enderley is most evident in its children. “I used to help run after-school holiday programmes, and I would ask the kids what their dreams were, and they would have no idea what I meant.”

She might take a group to a “posher suburb” for dinner, and says it was disheartening how out-of-place they felt. “Just to get somewhere, you might need to encourage them to dream of packing shelves at The Warehouse. But then they go home and they’re back in a place where no one gets up to go to work.”

Almost half of people living in Enderley earn less than $20,000 a year, while the median income is $22,500.

Annie says depression is something that bubbles beneath Poet’s Corner. “Sometimes encouragement has to come from us wahine, because our men have taken a lot of blame. People say things like, ‘Look at your boys,’ or ‘Look at your family.’

“When our men are down, they can go right down. And some of them don’t go down on their own.”

Raymond Bird used to run his family trust’s liquor store at Five Cross Roads and remembers alcoholism being rampant. He says the store was one of the top 10 liquor outlets in the country; “maybe higher than that in terms of turnover.”

There were also armed hold ups, and “rough fellows” walking in and grabbing boxes and walking out saying, “Go on, stop me.”

He remembers people spending what money they had, living each day at a time. “I suppose my fallback position was that if it wasn’t me [selling them alcohol], it would be someone else. If it wasn’t alcohol it would be something else,” he says to himself.

One of Annie’s regular visitors is Charlotte Reti, who has lived in the same home on Byron Road since 1962. Back then, she and her husband Merv visited the Māori Affairs Department and were offered the new house for £4000.

Charlotte’s husband, a plasterer by trade, died 17 years ago, and her children, grandchildren, and 25 great-grandchildren have all moved, mostly to Australia.

Charlotte is quieter than Annie. She sits upright with her hands clasped and pauses between words as if to ensure each one carries the appropriate weight.

Like her friend, she is torn between her love for Enderley and the necessity of recognising its problems. Poverty, she says, is a “horrible circle,” and a disease that never left. “That, I think, is due to the world not helping us make that change, or integrating families and providing them with opportunities to get out of this kind of life.”

She believes many of Enderley’s issues stem from it being treated as a “dumping ground” by housing providers. “I hate that it’s always been convenient to put people experiencing the same types of problems together and let them decimate each other. I have seen so many families decimated.”

She lost count long ago of the fences, including hers, that have been smashed in fights. “I really believe that if more people had owned their own homes, their attitude about ownership and pride and improving their lot would change. Politicians should provide families with better means to own their homes.”

Charlotte often thinks about the names of places. She thinks about the names of the poets who adorn Enderley’s street signs. Her address comes from Lord Byron, a notorious aristocrat who was rumoured to have had a tryst with his half-sister. Adjoining her street is Spenser Road, named after a 16th century classicist whose remains rest in Westminster Abbey.

Charlotte likes the idea of changing the street names. Perhaps Rakuraku or Tuwhare? “I suppose it is one thing to change a name, but it doesn’t change people’s circumstances. It wouldn’t change the atmosphere or the distribution of wealth, but I still like the idea,” she says. “Perhaps going to the mana whenua and asking the council if they would consider it would be one small piece of the puzzle of lifting the self-worth of some of our people.”

Alvina Edwards is less equivocal about the street names. “They’re a constant reminder of colonialism.”

Two years ago, she started a petition to remove a statue of Captain Hamilton in Civic Square. Hamilton was a British soldier who fought in the New Zealand Wars and died at the Battle of Gate Pā. She says his name was imposed on the city, which was settled 800 years ago by Māori from the Tainui waka.

She proudly remembers once storming the city council chambers with a megaphone to accuse a councillor of racism, and being “chased around.”

That night, she plans to attend an evening “Meet the Candidates” hui at the community house. The local government elections are in a couple of weeks, and the mayoral, and Hamilton East candidates are invited.

“You won’t see too many people around here going. Why would they want to go to a meeting when they don’t know what they can put on the table tonight?” says Alvina.

Like Charlotte, she says the area has been neglected by those in power. “Politically, everyone bypasses Enderley. And local government thinks it can come here and tidy the roads or plant a few trees and it’s going to be enough. Maybe some of them need to come and stay for a bit longer on Shakespeare and Tennyson.”

She has a list of questions written on a notepad. “I’m a heckler,” she warns, with a twinkle in her eye.

Come 6pm, Alvina Edwards’ warning proves prophetic.

Four mayoral candidates have shown up, including Paula Southgate, who would go on to win, and James Casson, who recently defended himself after writing a Facebook post calling refugees “scum”. The incumbent mayor, Andrew King, never shows.

About a third of Hamilton voted in 2016. Those who did were proportionally older, whiter and richer. A few days before, a mayoral debate hosted by Mike McRoberts in the Claudelands Events Centre filled the room.

Tonight, Southgate and Casson each make a two-minute pitch. The latter tells of how “Enderley has been neglected over time,” to which Alvina loudly scoffs.

They leave before taking questions. “We clearly weren’t their priority,” Alvina quips.

A dozen people running for the city council’s eastern ward then neatly assemble in a row of a plastic chairs at the front of the room. There are fewer than a dozen locals in the audience.

Alvina raises her hand. “I have eight questions, but some of them were for the people who just left.”

She asks about institutional racism in Hamilton, and is interrupted by a councillor seeking re-election who calls the term “gibberish”. He was the councillor Alvina hounded with her megaphone.

Among rambling speeches about rates and council debt, only a few words resonate with the few watching on. “Driving to work feels like living in two different cities,” says Kesh Naidoo-Rauf, who lives in Enderley. “Someone who lives here should represent you in council.”

Another candidate, Maxine van Oosten, is praised for plainly stating there should be more brown faces in the council chambers.

The moderator allows a final question, and again Alvina raises her hand. “I’d like each candidate to give me their definition of white privilege, please?”

There are groans from the front, and behind her another local shouts her down. “I’m white and I find that racist,” he says. The moderator waves his hand and dismisses the question and asks for a few final words.

Having been badgered for most of the night, the councillor seeking re-election thanks the few who turned up, “except Alvina”.

Afterwards, as everyone helps stack the plastic chairs, Charlotte Reti, who has patiently watched, says the lack of attendance was disappointing, but more so that the few mayoral candidates were only there for a moment.

“That says it all. It’s a them-and-us thing. They can talk about rates all they like, but she’s the one who stayed till the end,” she says, pointing at 26-year-old candidate Louise Hutt, “so she’ll get my vote.”

Annie Williams talks with 2019 Hamilton mayoral candidate Louise Hutt.

Annie Williams talks with 2019 Hamilton mayoral candidate Louise Hutt.

Annie is not disheartened by the turnout. “Our families won’t come out when it’s this cold.”

She has helped arrange for a council gazebo to be put up on her front lawn that Saturday, so visitors and passersby can be encouraged to register to vote.

Council officials asked to do it the following weekend, but Annie told them it would be too late. “You have to do it this Saturday,” she told them sternly.

“I’m all about getting the young ones involved, but I tell you, getting people around here to vote can be like pushing shit up a hill,” she laughs.

The heavy winter rain has flooded the entrance to Marlowe Street and the end of Yeats Crescent. On Keats, the pup has crawled back under the house.

Despite the downpour, there is a steady stream of people walking in and out of Annie Williams’ shed.

For years, Annie was known for giving spare food to people in Enderley, and across the city, for nothing. About four years ago, she joined forces with a food rescue group called Kaivolution to supersize her retirement enterprise.

Most days, often with Arctic and her own pup, Bubba, riding shotgun, she drives to Frankton, picks up as much food as possible from Kaivolution, and returns it to her shed.

The food comes from bakeries, cafes, and supermarkets that would ordinarily throw it out close to its sell-by-date.

Annie's gransdon, Arctic, stocks shelves with bread

Annie's grandson, Arctic stocks shelves with bread

On this particular Tuesday, when she returns, half-a-dozen locals are ready to help her unload bags of tiger sticks, buns and sourdough loaves. They line a table with bottles of Italian dressing and tubs of horseradish sauce and soup mix. There are jars of preserves and bolognese sauce, and sachets of baby food and whole boxes of mayonnaise bottles.

On hand is Hemi, who will stay in the shed until all the food is gone. He and his partner Diane often help Annie.

“It’s a good thing Annie is doing,” he says. “When you see something like this, you’ve just got to help out.” He and the other volunteers are among those short of food, and after pitching in, take what they need. Hemi points to a few cheese rolls. “You can cook these up with some spaghetti and it’s real good.”

First to arrive is a woman, warmly greeted, who tells Annie, “Sometimes things are just so much more expensive than you realise.”

Then comes a young father carrying his barefoot son. He tells Annie he is more hard-up than usual. Hemi encourages him to take some of the baby food and a few bags of bread. “Fill up a whole box, bro.”

In a quieter moment, Hemi says, “There are a lot of people struggling, but some of them just won’t come here and get some kai.” Are they too proud? “I guess. We try to take some round to people, but what more can you do?”

As the food is taken, Annie warns Hemi she is likely to get a “super load” from Kaivolution tomorrow. When there is more, people come from further away.

Everyone who comes practically sings Annie’s name, but she shrugs them off with a gentle humility.

She has always been community-minded. Thirty years ago, when they lived on Blake Street, Annie’s husband Toherangi set up a makeshift boxing gym in their garage. He trained the rangatahi, while she looked after the admin.

They paid for the equipment out of their own pockets, and encouraged troublesome youngsters to come in off the streets. Within a year, about 100 kids had signed up.

“We both worked, you see - he in the night and me in the day - so we could afford to buy the stuff,” she says. “My husband came from a boxing background so he thought, ‘Oh well, better get something happening with these mischief kids,’ so he went and put a ring in our garage!”

He named it Ngā Tamatoa o Kirikiriroa Boxing Club. Annie remembers some boxing officials being too lazy to learn how to pronounce it, simply dubbing it ‘Williams Gym.’ “That used to really upset him. He didn’t realise that people had a problem with Māori names. He thought everyone at least should know the Kirikiriroa part, but they didn’t.”

After a few years they had to close their garage. “He got too sick, you see,” she says. “We didn’t realise it for awhile, but it was the cancer.”

Annie’s Corner, as she calls it, is another way for her to give back to her tūrangawaewae. Poet’s Corner is her home, not just her four walls.

“You can talk about things, but you have to make it happen.”

Hemi and Diane in Annie's shed

Hemi and Diane in Annie's shed

As the last few bags of bread are taken, Hemi tells about how his place on Yeats Crescent is falling apart, and when he and Diane eventually move out, he reckons Housing New Zealand will demolish.

Some gang members recently moved in next door, which spooked them a little, until they brought them some free kai and were later invited for a hangi.

Now it’s all good. “It’s OK if you know them.”

Like Annie, Charlotte has always loved her street. Some of her fondest memories are of the rain.

“My home is on a curve, and right at the front, by the mailbox, is a road sump. When it really rains, like the rain we’ve had this winter, all the water starts to culminate right in front of my place. When the street used to flood, almost from one end of Byron to the other, all the kids used to come and swim in it.”

One by one, they would appear with their buckets and their bikes and Charlotte remembers them having the time of their lives. The flooding would bring the street together.

“It was almost like a party. There would be screaming and yelling and the parents would come out and you could guarantee they would all go over to somebody’s place and the kids would get dried off and everyone would get fed.”

Her children call Poet’s Corner “the hood”. After moving on, it has become an affectionate term. “It’s about the people, and their connection with the friends they grew up with.”

The hood, she says, is about striving for something. “It’s about teaching parents to be parents, and teaching men and women the right skills. And yes, sometimes they need a handout, but you’ve got to allow people the time to cope. And it’s a lot harder when they’re constantly being rubbished.”

Charlotte says over time, names like Shakespeare and Tennyson developed stigmas that were hard to shake. “If you lived on Shakespeare Ave, that was the pits! And you first hear about it through the young ones.”

Now, as her young ones have grown up and built their own lives, Charlotte says they laugh about names like Shakespeare and Tennyson.

Yet they are still protective, and woe betide the wrong person who insults Poet’s Corner. “I’ve had a happy life, and I’m proud to say that we brought up our children the best we could. And you know what? I’m happy to say that this is the hood.”

When Annie was young, before she first moved to Enderley, she remembers visiting from Hawke’s Bay with her eight siblings. Her mother, wanting to be closer to her whānau, was scoping the area.

“A house came up on Shakespeare Ave, but it was one of the double-storey ones. My mum was quite a big lady, and I remember her growling at the housing people. ‘How am I supposed to get up those stairs?’ she would say. “But I know she wanted us to be here.”

The morning Sergeant Craig Taylor arrived in Poet’s Corner eight years ago, after unlocking his new office and setting down his bag, Annie appeared at the front door. She was the first person he met in Enderley.

“A lot of communities like Enderley have people like Annie, and when they come to the surface, it can make such a difference,” he says.

And people like Annie will never give up on their home, or their community. Poet’s Corner is something they can call their own.

From her kitchen window, Annie is able to see the roofs of the eight new homes on Shakespeare Avenue. More may have been promised, but this is a start. “Have you seen them? They don’t look bad, eh?”

Some problems will not quickly disappear, but she has hope.

She mentions Raymond Bird’s new commercial development at the Five Cross Roads. A gym, hairdressers, Indian takeaway, and kebab shop recently opened on Fifth Avenue, and in a couple of months, a laundromat and an American fast-food franchise will open. Next year, work will start on “New York-style” apartment blocks.

“Many of us are thinking, gosh, it won’t be long before we’re a part of the CBD,” Annie says with wide eyes. “We’re very close to Claudelands and the city is just there across the river. We kind of feel like we might be pulled in.”

Distracted again, she tuts as she notices the puppy wandering in the street. Her neighbours are still not back.

Next door, children play in the street as their father mows the lawn. Another passer-by waves at Annie, and she waves back.

Annie rents her home for $100 a week from Housing New Zealand. She will probably never leave. She stays because for her, it is still papakāinga living, even if her blood is spread out across land and ocean.

“If I could take that fence down, I would,” she says, again pointing out of her window. “It feels like home here. It feels like you’ve been here all you life and it’s your tūrangawaewae.”

Reporter Max Towle

Executive editor Veronica Schmidt

Videographer & photographer Luke McPake

Art direction & design Luke McPake

Drone photography Aaron Carter

Aerial survey images courtesy of Hamilton City Libraries.