A POOR OUTCOME

Māori, poverty and the struggle for survival

Poverty continues to impact Māori far more than non-Māori and the knock-on effects are brutal. Aaron Smale heads to Tairawhiti and finds a community taking matters into its own hands.

The fish and chip shop is doing a brisk trade at the Kaiti Mall with cars that have seen better days pulling in, pulling out. The early evening sun slants across the shop frontages in the Gisborne suburb as the city winds down for the day. Mothers with toddlers in tow lug baskets of clothes on their hips as they make their way to the laundromat. Others lean on cars gossiping and joking.

But a couple of doors along there is a bigger attraction. Kids scramble out of cars and race each other to a nondescript building at the corner of the mall. Something exciting is going on inside: the weekly chess club night.

The movie Dark Horse was shot in this neighbourhood. It tells the true story of Genesis Potini, a man with mental health issues who has a genius for chess. He passes his passion on to the local kids and in the process gives them hope.

Potini isn’t just a character from a film around here – one of his kids is in the club. And the poverty-related struggles portrayed in the movie didn't fade away after the credits rolled.

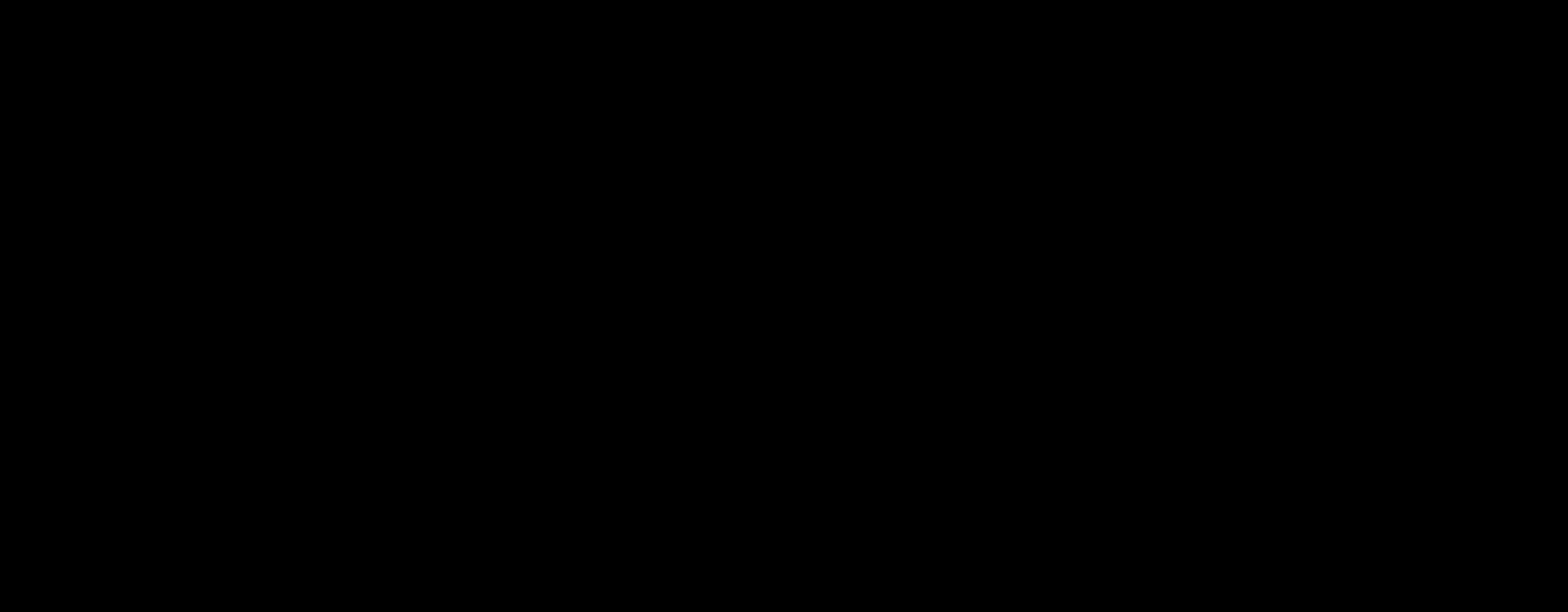

Tuta Ngarimu

Tuta Ngarimu

Tuta Ngarimu has the physique of a bouncer, the demeanour of your favourite uncle. A former Mongrel Mob member of 30 years, he exudes warmth and aroha. His cheerful tone shifts slightly though, dipping into a sterner, more serious range, when he’s asked about the chess club. “My focus to get the chess club up and running was around suicide.” Ngarimu is the event chairman for the Nāti 4 Life Trust, a suicide prevention group. “It’s pretty scary stuff we’re dealing with out there at the moment. Especially when you’ve got our kids killing themselves. It’s really, really, really worrying when you see that. Statistics ... pop up on Al Jazeera saying that Māori – indigenous Māori – have got the highest suicide rate between 18 and 24. That’s around the world what they’re saying that about us in New Zealand.”

It's not just media scaremongering. While New Zealand sits mid-table among OECD countries for suicide, the statistics for young Māori males are higher than the overall rates for men in Lithuania and South Korea - countries who lead the grim statistics. While in 2017 Lithuanian men died from suicide at a rate of 43.9 per 100,000, in 2012 Māori males aged 15-24 died at a rate of 48 per 100,000.

“We’ve got the highest addiction rates, we’ve got the highest drink-driving rates, especially for rangatahi [youth],” says Ngarimu. “We’ve got all this stuff that’s been going on with our whanau and we’re trying to dull what’s going on. At the beginning it was a recreational thing. But now it’s become normalised.

“So I thought, looking at a lot of the statistics and that, we needed to build up the resilience in our kids. And chess to me is that. So it teaches our kids that if there’s an action there’s a reaction. It teaches them how to plan 20 steps ahead, so you’re always planning ahead of yourself. Whereas if you look back at a lot of our kids that have passed away through suicide, maybe at that time they just had no options. That was the only option left. So I’m thinking if we can build that resilience up in our kids so if they take a hit, there’s something in there to pull them out.”

Ask Ngarimu why he thinks kids are taking their own lives and he loops back to his own childhood. The families he sees who are in dire straits now are whanau he grew up with. Many are his relations. And in Gisborne everyone is related to someone.

The world he grew up in took a turn for the worse around 30 years ago, he says. If you wanted a date, 1984 would be a good place to start. “I guess when you look back at the big picture, back in those times we were just [entering] Rogernomics.”

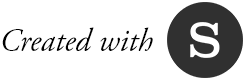

Prior to Roger Douglas's introduction of neoliberal economic policies, he says, there was affordable housing and plenty of jobs in Gisborne. “You had the Gisborne freezing works, you had the Wattie's company here. That provided income for a lot of whanau.”

Kaiti Freezing Works, circa 1910.

Kaiti Freezing Works, circa 1910.

When the jobs disappeared, the issues began and built over time, he says. “When you look back on the statistics, you start seeing over the last 20 years that there’s been a gradual climb with a lot of statistics around abuse. It all stems from poverty really.”

As the state corporatised and privatised government departments, withdrew economic controls and subsidies, and dismantled the centralised welfare system in the 1980s, it also stepped up its hard-nosed approach to those who were left behind in the wreckage, Ngarimu says. He witnessed a turn in government policies that he says started punishing people who had worn the brunt of the economic upheaval. That approach further alienated people who were already struggling, escalating problems rather than solving them. It also put them in a place where they made decisions that were borderline illegal just to get by, he says. This kind of behaviour then became habitual and, eventually, entrenched.

“It’s just an ongoing war to survive. An ongoing war. As soon as you wake up there’s something, whether it’s your rent going up, the price of food, whether you can’t afford to send your kids to school, whether you’ve got no petrol to put in the car.”

“Everyone is shifting the goal posts all the time. There’s no solutions behind any of this other than to keep everybody on their toes. Alright, we can’t come up with any jobs, but we’ll keep them on their toes any way and make them tick all these boxes every week.”

Add to that racism from government agencies, which Ngarimu says he sees frequently. “As soon as you walk in with a Māori family they get treated like … you can feel it. You know they’re not welcome there. I’ve taken in someone who’s not Māori and it’s a totally different response. So it’s blatant out there.

"They just keep tramping and tramping our people into the dirt"

“Through government policies, they just keep tramping and tramping our people into the dirt all the time. All these different policies that keep coming up every three or four years.”

Take the Work and Income rules around temporary work. “You go out, it rains for a week. Then that whanau are at home for the rest of the week and it’s just never-ending. You can’t go back on the benefit because you’ve got a part-time job. So you don’t say that you’ve got a job, you stay on the benefit just to make sure that if it rains at least you’ve still got the benefit to rely on. So it kind of pushes everyone into that undercover life just to survive. Whanau are placed into this position just to be able to put food on the table.”

Ngarimu says his observations are borne out by statistics, which show widening inequality post-Rogernomics. Until the 1990s, Māori rates of home ownership lagged behind Pākehā, but were on a gradual upwards trajectory, with more than 50 percent of Māori owning a home in 1991, even as Māori and Polynesian unemployment sat around 25 percent. Unemployment rates eventually dropped, but Māori home ownership declined by nearly a third, and by 2013 was about 37 percent. Pākehā home ownership also dropped, but from a high of above 75 percent to just below 70 percent.

One factor is that house prices have vastly outstripped wage growth. Even in south Auckland’s Otara, at the low end of the city’s market, houses typically sell for about $580,000. Many of the houses on the market are now being bought by investors (this is also happening in places like Gisborne and other regional towns, as Auckland property owners leverage their equity, pushing up house prices nationally). Ray White real estate agent Tom Rawson, who specialises in south Auckland, says of the roughly 4500 homes in Otara, 3000 of them are owned by Housing New Zealand, probably 900 by investors and 600 are owner-occupied.

Owning a home is one thing. Not having shelter at all is another. In Auckland a recent survey estimated that 800 people were living without shelter – sleeping rough or in a car – across the region. While Māori make up only 11 percent of the Auckland population, they made up 42.7 percent of those without shelter and 39.9 percent of people sleeping in temporary accommodation.

While house prices, rents and living costs have rocketed over the last few decades, wages have not kept pace, pushing more Māori, typically already suffering poverty rates double the non-Māori population, further into deprivation. A household income report from the Ministry of Social Development, while debating a definition of poverty and whether it exists in New Zealand, had this to say: “No semantic niceties can change the reality that there are children in New Zealand who are going without the very basics, without items and experiences that virtually everyone would say that all children should have and none should be deprived of in New Zealand in 2017.”

If a kids' chess club seems inconsequential in this bleak picture, the club is one small part of a community response. That response is not based on any grand economic plan or political agenda. It’s more about trying to restore people’s dignity.

Ngarimu and a group of volunteers run Ka Pai Kaiti, a trust that is part of a loose network of people trying to turn things around in Gisborne and the East Coast, one of the most economically challenged regions in the country and one with a high Māori population.

Asked what their work involves, Ngarimu answers, “Whatever walks in the door.”

People are coming through the door, he says, because they’re reaching out for support and there’s not the support out there. “I had a guy [who’d been] up for 14 days [on P], walking in, wanting help. I know the help that that guy wanted. And I knew that we couldn’t give him that help.

“Are we waiting for a guy that’s flipped out and hasn’t had a sleep for weeks to bloody shoot everybody before we get anything bloody happening? It’s kind of like they’re waiting for something to really tip over the edge before something happens. We know there’s nothing out there to support them, so we do it ourselves.

“We thought, let’s put it out there, so we set up a support night for whanau. It could be grandparents, it could be a brother or sister with somebody that’s on meth. Grandparents were the main ones we were looking at because a lot of grandparents are looking after the mokos and they don’t understand all that meth thing and they’re scared. So we decided to have this night where they could all come in, sit in a safe space and just talk to each other. If there’s whanau that come in and they want to get off meth, we’ve managed to find a process where we can get them support out of Gisborne. That’s another big barrier for our whanau here. All the support seems to be out of Gisborne.”

The gap between the government agencies who have the power and the resources and those in need has become something of a standoff, he believes. Those agencies are disconnected but they are also harming communities. “I started seeing domestics out the front here. I’d go out here and there’s a laundromat next door, kids in there because it’s warm. I says, ‘What are yous doing?’ ‘We’re waiting for mum and them.’ ‘Where are they?’ ‘They’re in there’.”

“In there” was the pokies.

“So I started digging down into what was going on ... The misery that was going in there. A lot of the time the kids were involved when they’re having domestics out there, about losing all their money in the pokies. So we saw the harm and the damage it was doing to our community.”

He discovered, to his horror, that in one year $12 million had gone into pokie machines in the Gisborne region.

“Twelve million dollars. In one year, for God’s sake. That would clothe and feed the whole of the Tairawhiti.”

He found sports clubs and other organisations were getting a small proportion of that money, through community grants, but most of the rest went into the pockets of the owners or to Internal Affairs. “Ten to twelve million for Internal Affairs came out of the Tairawhiti region.”

“We decided to do something about it. We set up a protest. We got together and came up with a strategy on how we’re going to close them down. Two years later that strategy has worked. They’re gone. That just goes to show that if you really care about something and you can see the harm that it’s doing to our people, you do something about it and there’s a good chance that it’s going to happen. That’s a good example.”

Ngarimu is not the only one involved in that “flaxroots” political pushback.

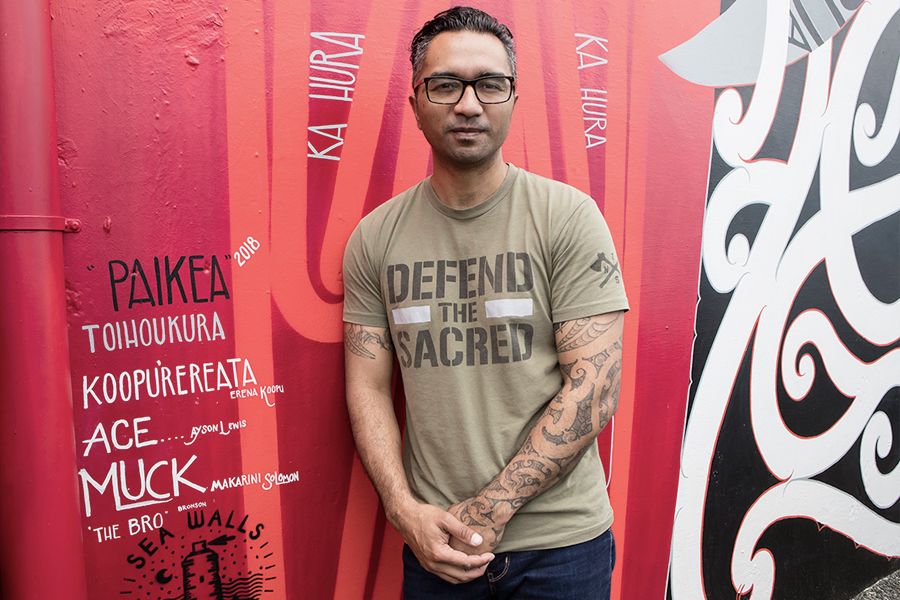

Josh Wharehinga wouldn’t look out of place amongst the hipsters in Cuba Street in central Wellington. But by his own admission he’s always been a Gizzy boy. Born and bred in the region, he went to university, only to boomerang back as soon as possible. It’s the only place he wants to be.

Josh Wharehinga

Josh Wharehinga

He is a district councillor and also on the boards of Tairawhiti District Health Board and the tertiary education provider Te Wānanga o Aotearoa. He says being in the governance space has opened his eyes to inertia at the political level.

“Every governance role that I’ve come into, I’ve gone, I’m going to do this, this, this and this. This is going to be radical, this is going to be massive. I was like, man, I’m going to do some cool stuff here, I’m going to progress some rapid change. And then you hit the bureaucracy. This wall of bureaucracy, this wall of compliance and policy and all of those kinds of things.”

What is not new to him is what he sees as the prejudiced assumptions from those at the top. He finds it both slightly amusing and frustrating when politicians choose to vilify certain marginalised groups of people, because he usually belongs to those groups.

“It’s hardcase politicians always throwing the gang thing out there, or always throwing the beneficiary thing out there, always throwing the solo benefit thing out there, always throwing the Māori thing out there, cos I’m those things. They’re like, oh there’s a problem with – insert Māori statistic – and 99 times out of a 100 I am one of those statistics.

“It always cracks me up when those politicians are having those kind of conversations, because 99 times out of a 100, they’ve never been on the DPB, they haven’t grown up in a gang-affiliated environment, they don’t actually know, meaningfully know, about the struggle that a lot of New Zealand and a lot of Māori go through. It would be like me trying to represent Federated Farmers with my garden of silverbeet in the backyard. Oh yeah, I know exactly what it’s like to till the ground. I can talk about silverbeet but that’s probably about the limit.”

When he came back to Gisborne from university he got involved in teaching, then worked as a social worker for an NGO. He’s witnessed the negative reaction from people who have a long history of reasons to distrust authority and he finds their alienation completely understandable.

“I remember turning up to a house. I never introduce myself as a social worker. I never, ever said I was a social worker because as soon as you say, “Hey, my name’s Josh, I’m a social worker,” they’d automatically think I was CYFS and, you can f*** off, and all that kind of stuff. Which is a fair reaction, you know. CYFS, child welfare, have a history of coming in, messing up families, taking away children, interrupting their whakapapa. That’s a justified reaction.”

He frequently sees the disconnect between what the community needs and what various agencies provide. Ka Pai Kaiti and other community-led initiatives have sprouted up to fill the need, but they operate on little to no money.

“The system is not of us. The system is in Wellington, that’s where the system is. The police is not a regional organisation. Oranga Tamariki, formerly known as CYFS, is not a regional organisation, it’s not a Gisborne organisation.”

“If the people that are of here are working with the families that are of here, then it’s a lot less of a hurdle to be able to engage with those whanau and move our region forward. Move whanau forward.”

Hilton Collier

Hilton Collier

Hilton Collier has just flown home from Wellington and orders the first round at a pub overlooking the Turanganui River. A stone’s throw down the river is the spot where Captain Cook first greeted tangata whenua, after a fraught – and deadly – first encounter.

Collier is Ngāti Porou through and through and is the general manager of Pakihiroa Farms, a group of tribally owned farms on the East Coast.

He sips the froth from the top of his first pint and ponders which direction to take with the questions put to him. I mention the conversation with Ngarimu and the work he and others do. He knows them and the people they serve. They’re whanaunga.

“You have a group of people who understand reality at the coalface, they understand what it means, in business-speak, to be consumer-centric. Their consumer happens to be a beneficiary or someone who has run into trouble somewhere, so they understand the issues they’re facing and understand the support they need. Unfortunately the system is compartmentalised and resourced to do something very specific. So the solution becomes very prescriptive. You cannot prescribe success.”

He also sees the entrenched poverty and the negative spin-offs that have become generational. But he doesn’t believe that the current approach to those caught in that trap is working.

"When you're on a subsistence level of income, it's about survival."

“When you’re living day to day you can’t sit back and look and think, right, I need to do these things because this is where I want to be in five years' time. You can’t think about where you want to be in five years' time if you can’t get through the day. When you’re on a subsistence level of income, it’s about survival.

“The challenge is, what are the interventions needed to provide them with the freedom to think? Hey, I can go and do some seasonal work and I’m not going to be punished by a social welfare safety net that is punitive. If the job is only for two weeks and they can get two or three times the dole for a couple of weeks, we should encourage them to take it. They’re not going to take two or three weeks' work when they have to have a stand-down of how long? Why are we punishing them?”

To see how he reacts, I wheel out the talkback radio line about Treaty settlements and Māori privilege.

“Don’t f***ing start me on that,” he retorts. “What’s the value of the Waikato? And how much did they settle for? A few cents in the dollar. “There was this company called South Canterbury Finance,” he says in a sarcastic tone. “They went bust. What did they do? The government put in money to compensate these poor people, these financially smart, literate people, who lost their savings.” Treaty settlements only ticked over a billion dollars in recent years, he says, well short of the one-off government bail-out of South Canterbury Finance. “We have agreed to settle for a fraction of what should have been settled for to allow us to move on.”

Going back to Sir Apirana Ngata and earlier, Ngāti Porou have put a high value on education. But Collier says the current education system is not delivering to Māori. “The education system really grates. We seem to have a system of kura kaupapa doing extraordinarily well. They punch well above their weight for their resourcing because they deliver and teach in a way that connects with us. I’m tertiary qualified, I’ve come through the education system. You could argue that I’m evidence that Māori can adapt to the system. But I hated it. The only thing I hated more was failing.

“Recently I was up at Mum’s, and my nieces go to kura kaupapa in Ruatoria. What impressed me was at 5.30-45 the kids came home and they were excited and talking about school and all the things they’d been doing and learning. They were really engaged and focused and interested. School finished at 3 o’clock. The teachers had been there with them until the same time. They seemed to have found a way to deliver the curriculum that appealed to the kids, engaged the kids and excited them. When people are happy, they perform.”

Wharehinga is reluctant to specify a magic bullet to turn around the economic prospects of the region, or other areas with a high Māori population. Like Collier, he believes education is a key.

He says the best investment that can be made is in people – to invest in their ability to reach their own potential and the potential of their whanau. Do that right and they’ll find their own solutions. Tino rangatiratanga.

“I think if we improve our people, those things like meaningful jobs etc, etc will follow. We’ve gotten into this mode where we think that, I mean we as a nation, we as a global people, where we think one huge organisation is going to be the saviour for our regional town. We praise job creators. Where are the job creators? Well, the job creators live here. Let’s improve their lot, let’s improve their education, let’s help them realise their dreams and they’ll create the jobs themselves.

“If we rely on the job creators whose economic model is, let’s pay all our workers the least amount possible, squeeze as much as we can out of them, do I want that kind of employer here in Gizzy? Probably not. What’s a better option for me is improving the lot of our people. Giving them the options and the access to the educational pathways that is going to be meaningful for them.”

Ngarimu hasn’t got a pat answer for success either. But he also knows there’s something powerful about restoring people’s hope and belief in themselves.

“We've got a lot of good stories here. Stories of people being in a really terrible space and I’d like to think through our help getting them into a better space. We see a lot of that. We also see a lot of our community come in here, wanting to help. We also see and hear people of all different races coming in through here to try and help. We see a lot of goodwill in our community coming in here because they know what we do. We do everything here. It’s a pretty inspiring place to be. You’ve got so many people coming in, wanting to talk and share ideas. There has been some life-changing stuff happen here for whanau. And that’s why we keep doing what we do because we have seen that it works.”

Reporter Aaron Smale

Photography Aaron Smale, Claire Eastham-Farrelly, Luke McPake, Paul Rickard - The Gisborne Herald, William Archer Price - the National Library of New Zealand

Editor Veronica Schmidt

Sub-editor Mark Broatch

Graphic designer Scott Austin

Made possible by the RNZ/NZ On Air Innovation Fund

Where to get help:

Need to Talk? Free call or text 1737 any time to speak to a trained counsellor, for any reason.

Lifeline: 0800 543 354 or text HELP to 4357

Suicide Crisis Helpline: 0508 828 865 / 0508 TAUTOKO (24/7). This is a service for people who may be thinking about suicide, or those who are concerned about family or friends.

Depression Helpline: 0800 111 757 (24/7) or text 4202

Samaritans: 0800 726 666 (24/7)

Youthline: 0800 376 633 (24/7) or free text 234 (8am-12am), or email talk@youthline.co.nz

What's Up: Online chat (3pm-10pm) or 0800 WHATSUP / 0800 9428 787 helpline (12pm-10pm weekdays, 3pm-11pm weekends)

Kidsline: (ages 5-18): 0800 543 754 (24/7)

Rural Support Trust Helpline: 0800 787 254

Healthline: 0800 611 116

Rainbow Youth: (09) 376 4155