ROUGH JUSTICE

Māori and the criminal justice system

More than half of the prison population is Māori. Is the criminal justice system biased, or is this bleak statistic a symptom of societal imbalances?

Aaron Smale reports.

Teresa Aporo tried to take away her mother’s pain and ended up in jail.

“In 1998 my mother went into hospital. It was diagnosed that she had cancer. They said to her that she’ll probably die of heart disease before the cancer gets her. That’s when I started getting into the cannabis. I was wanting to do something with medical marijuana, so I started growing.”

She got caught and went to prison for 13 months.

“I went into jail at the end of 1999. My mother died in 2000, 23rd of March. My mum knew what I was doing and approved of it because she couldn’t see any victim.

Teresa Aporo

Teresa Aporo

“Two weeks before my mother died she rung the [prison] drug rehab unit and asked the manager if I could come home, if I could get leave, because she wasn’t going to be here much longer. So I got 40 hours' leave. I spent four hours travelling. I spent 36 hours talking with Mum. It was the best 36 hours I’d spent with her. But there was a goodbye, I’m not going to see you again. She died when I was in prison.”

Aporo found that the counselling and support that was provided on the inside dried up once she left prison.

“I got out at the end of 2000. Two weeks later I wanted to go back in. I just didn’t feel safe. There’s nothing for people. When you get on the outside none of that support is there.”

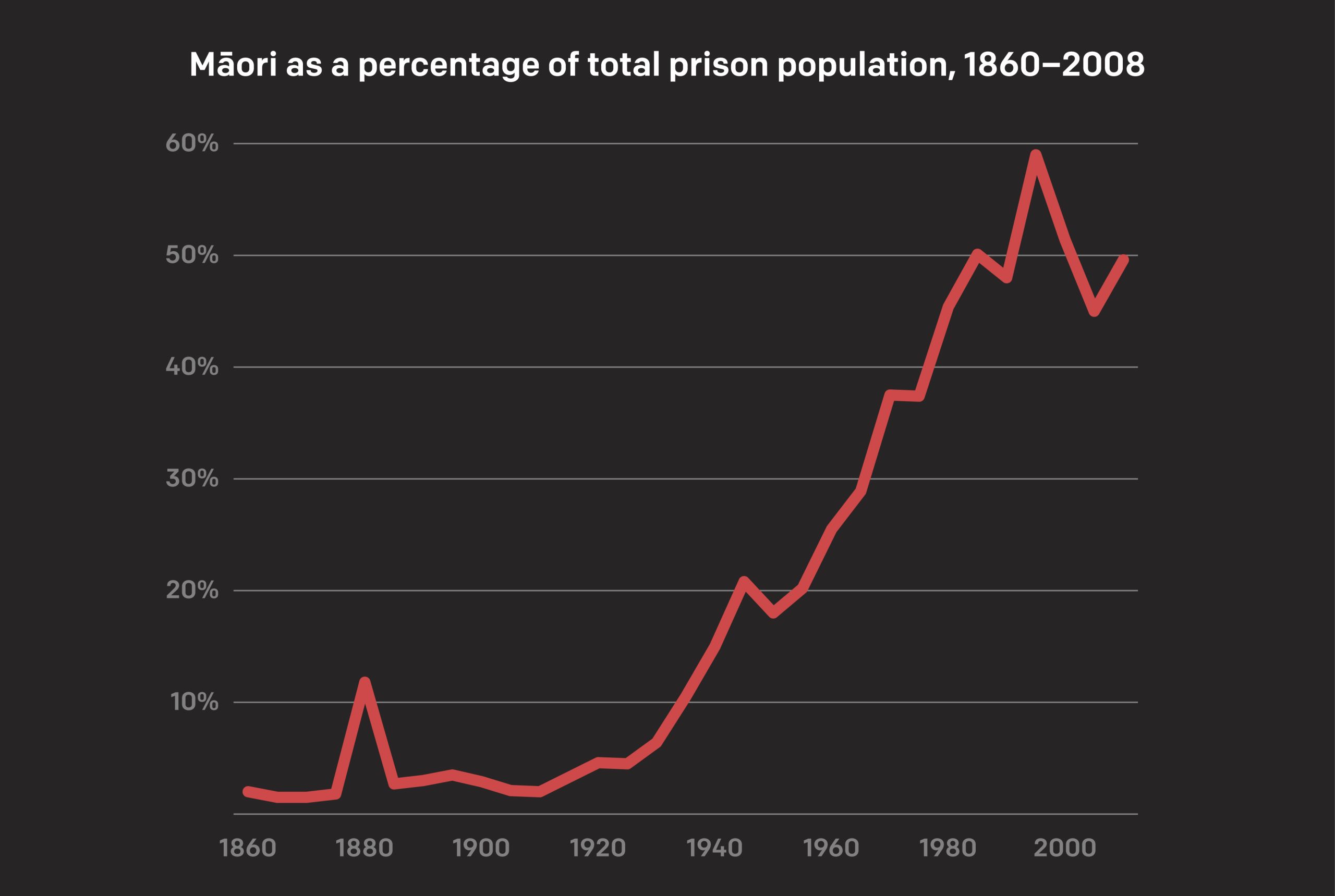

Her crime added to statistics that show in decades Māori have been caught up in the justice system at rates way out of proportion to their percentage of the population.

Moana Jackson sounds weary. When you hear what he’s been up to in the last four years – actually, make that 30-plus years – you begin to understand why. He has been relentlessly tackling the Sisyphean task that is the criminal justice system and Māori.

He has been writing a revised version of his report on Māori and the criminal justice system. The first version – The Māori and the Criminal Justice System: A New Perspective / He Whaipaanga Hou – was written in 1987 and has been a reference point for the discussion ever since, even though what Jackson wrote seems to have been largely ignored by those who could have changed things.

Revisiting the project – which he has never really put down – meant tracking down many of the original informants, of whom there were a couple of thousand. For the latest iteration he had the help of a couple of researchers and between them they spoke to around 4000 people.

He remarks that in some ways he could have saved himself some trouble and put a new cover on the old report, such is the lack of movement.

Has anything changed? “What’s the same is that the rate of imprisonment of Māori men is about 52 percent of the total prison population. What has changed is that the rate of imprisonment of Māori women has shot up to 64 percent of the female prison population, which makes our women, per capita, the most imprisoned indigenous women in the world.

“But overall there’s been no change in the lack of imagination. Thirty years, it’s almost the perfect time capsule really. The criminalisation of poverty has been part of the catalyst for the increased rate of Māori women in prison. It’s not the whole answer, but it’s brought a return of the Victorian-era notion of poverty being sinful and therefore a crime.”

Moana Jackson

Moana Jackson

“I often say you can’t isolate a Māori man in a cell in Paremoremo, a Māori woman in a cell in Arohata,” says Jackson. “You can’t isolate them from socio-historical contexts that have shaped our people. The economic forces which have driven those forces, the racism which underpins them. But the criminal justice system is not interested in context.”

Jackson’s original report made clear this context was crucial to understanding the high number of Māori who come into contact with the criminal justice system. In the introduction he states: “Because the justice system does not exist in isolation from the society it serves, any study of its processes must include consideration of these questions.”

In other words, if you want to understand the criminal justice system, you need to look outside it.

The report landed just as Rogernomics was being felt throughout the country. That economic upheaval changed many things, including the rates of incarceration.

Māori were a negligible percentage of the prison population in the early 1900s, but this started to climb rapidly in the middle of the century. By the mid 1970s it was sitting at just under 40 percent and surged through the 1980s, peaking at nearly 60 percent in the late 1990s. Today it sits at just over 51 percent.

Those rates are now well known but what is less often acknowledged is that Māori are also more likely to be victims. A recent Ministry of Justice survey found that “Māori (37%) were more likely to be victims of crime than the national average (29%).”

Why? The study notes that those who are younger, a solo parent, have lower life satisfaction or psychological distress and live in deprived areas are more likely to be victims of crime.

Echo Haronga was barely babbling her first words when Jackson’s first report landed. Now she employs her language skills and intellect as a defence lawyer in South Auckland.

She arrives at the Manukau District Court with the kind of professional attire and bearing that immediately signals she’s not here to appear in the dock.

Haronga has been working in criminal law for six years, first as a police prosecutor and since 2015 as a defence lawyer. Her bread and butter is defending clients who are charged with offences that attract prison sentences of 10 years or less.

The court, a concrete monstrosity looming over Manukau Station Road that was opened in 2000, has all the charm of Soviet-era architecture. The entranceway to the district court isn’t any friendlier, with an airport-like security check-in. Only there aren’t any flights to holiday destinations here. For some entering these doors it may be their last taste of freedom before a stint at one of Her Majesty’s residences.

Despite her relative youth, Haronga has noticed a shift in attitudes towards the inequalities in the criminal justice system.

“I’m not old enough to say what’s happened generationally. But it seems that society is only really just at a point where those statistics about those prison numbers are actually offending people. We’re only just getting to a point where people are going, ‘Oh, that’s not right’. I don’t know where it came from. Maybe it’s just in my generation. But in very recent history, middle New Zealand was very, very comfortable with those numbers. I think complacency has been a big part of it.”

Echo Haronga

Echo Haronga

Haronga is reluctant to put imbalances in the criminal justice system down to individual racism – she knows many of the police, lawyers and judges that work in South Auckland. But she says the reality that Māori end up being policed and criminalised more heavily is unavoidable.

“It can’t just be brought home by racism. That’s an inconvenient answer to anyone who works in the criminal justice system, particularly in Manukau. Our judges, our lawyers, our prosecutors, they’re incredibly aware, because we know the legal system and how it was maybe 30 years ago and we don’t want to repeat that. But at the same time we’re working in the system that we’ve got and it’s disproportionately stacked against Māori.”

Corrections’ own figures bear out what she and many others have observed: Māori get harsher treatment at every stage of the justice pipeline to prison.

Even allowing for a number of factors contributing to the high numbers of Māori in the criminal justice system, racial bias is impossible to ignore. A comprehensive study by Corrections in 2007 noted that “there are indications of a degree of over-representation related solely to ethnicity, rather than any other expected factor, at key points in the criminal justice system. Although mostly small at each point, the cumulative effect is likely to be sufficient to justify closer examination and investigation of options to reduce disproportionate representation of Māori.”

Haronga says the mountain of data is stubbornly consistent.

“It’s really difficult not to say that it’s racism because the data so clearly shows that. It’s hard not to look at that data and say, 'How can that not be racism?' It’s certainly not something we can rule out. But there are a whole raft of reasons that a police officer may ask to speak to someone.”

Haronga says the disparity in the numbers of Māori caught up in the justice system compared to all others often comes down to economic factors at every stage, starting with where police focus their resources and the make-up of the communities where that policing is carried out.

“The police, often not through intention, often reach for the lowest hanging fruit. We know that to be particularly unsophisticated crime committed by people from low socio-economic communities. We know from our data that that disproportionately affects Māori.

"If you have a police officer who is out looking to secure the community during the day he is disproportionately going to run into Māori young people."

“Generally speaking, my clients live in very high-density housing areas in overcrowded homes. A lot of their life is actually spent out on the street and I don’t mean in terms of being in a gang and street culture. I mean they physically don’t have living space. They spend time with their friends in open areas. If you have a police officer who is out looking to secure the community during the day he is disproportionately going to run into Māori young people.”

Economic factors also kick in when it comes to sentencing. For first-time offenders there are the options of diversion or being discharged without conviction, which mean that if an offender meets certain criteria their offending can be dealt with without them ending up with a criminal conviction. But the criteria can again come down to the offender’s economic position – whether they have the means to pay reparation, say, in the case of a careless driving charge that caused damage to someone else’s car but didn’t cause any injuries. It might also come down to a person’s job prospects and whether a conviction will harm their future career in the field they are employed in. If they are in low-skilled work or are unemployed, a conviction is not seen as such a threat to that offender’s prospects. Which gives no thought to a point in the future where that conviction will affect their job prospects and upward mobility.

One contentious area is the question of bail. Should someone charged with an offence be locked up while they wait for their court appearance or should they be bailed under certain conditions? Bail conditions were tightened in 2013, when Judith Collins was Justice Minister, in response to high-profile cases of violent crimes committed by offenders on bail.

But in most cases, bail is more mundane and being locked up can cause further harm rather than reducing it. Sometimes the main reason for bail being declined – and consequently a stint behind bars while waiting for a court date – is the absence of a residential address. “Those short sentences are usually a result of being declined bail because of a lack of housing,” says Haronga.

If that offender’s sentence options when they finally do get to court are prison or community sentence, some will take the prison sentence because they’ve already served time on remand. But this has implications for their criminal record: a jail term looks more serious than community service.

“Having already done your time in custody means you’re much more likely to throw up your hands and go, why would I want to come out and do community service on top of the time I’ve already spent just to get a better sentence on my record,” says Haronga. “I might as well just take the three months and call it quits. Then I don’t have anything else hanging over me from the court.”

Bail has a lot to answer for in terms of Māori accepting those terms of imprisonment, she says. “So you end up with a trailblazing record of imprisonment that you then have to declare to employers as well. If you did have employment you’ve probably lost it in that time [you’ve been inside].”

Those on short terms of imprisonment don’t get access to rehabilitation, she says, meaning they often come out with worse behaviour than when they went in. This is why prisons are known as “universities of crime”, she says. “A lot of my clients end up in custody because of repeat offending in the family home. It’s quite a common thing and it’s something people are generally unsympathetic for. But in prison, treatment for their use of violence and treatment for their expressions of anger has not occurred. They’ve just spent maybe the last six months penned in with a whole lot of guys who also aren’t receiving treatment who spend all their free time at the gym and who express themselves through violence. So it doesn’t really do anything for the families of those offenders who come out.”

Haronga says if that experience of a short jail sentence does anything, it makes it more likely that they’ll reoffend and that offending will be more serious. In other words, the system can amplify harm, rather than reduce it.

If you walked in off the street that August day last year, you would have wondered what they were all there for. The events centre in Porirua was filled with several hundred bureaucrats, politicians and various bods from various groups. A smattering of them were Māori. It was a summit on the criminal justice system.

A couple of hours into the day, MC Alison Mau was interrupted from the floor. It was Te Wheke from the film Utu, otherwise known as the actor Zac Wallace (who has since died). Wallace was at the back of the stadium but yelled out, “Where’s the Māori voice?”

It caused an awkward moment, and the question hung in the air for the rest of the day. Where were Māori in this discussion?

Later that day, Minister of Corrections Kelvin Davis addressed the elephant in the room: the high number of Māori tangled up in the criminal justice system.

In an interview with RNZ, he does it again, but first explains how he enjoys going into prisons and talking to those inside. He wants to hear inmate's voices and listen to what they think would make a difference and keep them out of jail.

“We sit down with groups of upwards of 20 people. I just pop that question to them: how do you need to be treated? It’s not just how you are treated in prison, how do you need to be treated before prison, how do you need to be treated after prison, so that when you leave here you never return? Because I turned up in a suit and tie I didn’t expect much of a response. I thought I’d have to drag things out of them. I tell you what, they just unload.

Minister of Corrections Kelvin Davis

Minister of Corrections Kelvin Davis

“I went into Whanganui prison. In the gym were about eight to 10 young guys working out. It was a cold call. I stopped and said, ‘Hi I’m Kelvin, I’m the minister.’ I said, ‘I’m interested, how would you like to be treated so you don’t return?’ They were just throwing so many ideas at me that I had to say, stop, stop. What you’re saying is amazing. I’ve got to come back with people with pens and paper so we can record this. So I went back last Friday and followed up.

“It’s fascinating what they tell you. You get a sense of their backstories, you get a sense of what we’re doing as a system that inhibits their rehabilitation. I mentioned in my speech yesterday a guy who has a non-contact order, he can’t associate with gang members. He said, ‘But my mother, my father, my siblings are gang members. We’re a third- or fourth-generation gang. You’re taking away my only support system and yet you don’t want me to reoffend. What options do I have if I’m living under a bridge?’”

Davis, like every Corrections minister, is caught between political and media calls for vengeance and the reality of the lives of those behind bars. Davis says it’s always a balancing act between the needs of the victims, the safety of the public and the need to reduce offending. Or, even better, prevent it.

“Fifty percent of crime is perpetrated against 3 percent of the population and that 3 percent is generally Māori."

“I heard a story today about a woman whose daughter was murdered with a hammer and she was attacked. Sorry, but the perpetrator of that I believe had to go to prison. But when he’s in prison how do we help him so that when he comes out, whether it’s in 20 or 30 years' time, how do we make sure he comes out a better person?”

He says that while the number of Māori in jail is high, so is the number of Māori victims.

“Fifty percent of crime is perpetrated against 3 percent of the population and that 3 percent is generally Māori. We’re actually talking about protecting our own from our own often.

“Corrections doesn’t have any say on who comes through the gates. Where Corrections' responsibility is to make sure that we improve [them] as much as we can inside those gates, so that those people come out better people. Whether they should be there or shouldn’t be there isn’t actually Corrections’ job to determine. That’s determined by the courts and the other parts of the system.”

He says that system is bigger than the justice system alone. Much of the prison population is functionally illiterate so improving education is a big part of the picture. Prison inmates also have higher rates of mental health problems than the general population. Corrections figures estimate that 91 percent of inmates have mental health or drug addiction issues. Whether they could access treatment in the health system before ending up in prison is a moot point. Even when they end up in jail, such treatment is usually only available to those doing longer sentences, which means those who have committed serious crimes.

Davis says addressing those broader inequities is a government priority. But he says there may also need to be a shift in public priorities and perceptions.

“Māori get it when we start talking about the justice system. They just get it. There’s very little explanation needed. In terms of that white, middle-class constituency, if we can get things right we’re going to make their lives better because if there’s fewer Māori in prison, fewer Māori in mental health facilities, if there’s more Māori in university, if there’s fewer Māori living under the poverty line, everyone benefits.

“My constituency is all of New Zealand, but I’m going to achieve better outcomes for all of New Zealand by focusing on those who need it most. They’re Māori, they’re low-income people. What that middle-class constituency needs to see is that what we’re doing is good for everyone.”

Is that a hard sell?

“It is a hard sell. But then again I’m not going to wait for their permission to make life better for my people.”

Davis’s media advisor is looking visibly nervous and interrupts. “We should probably wrap it up.”

If anyone has been at the coalface of Māori experience of the criminal justice system in the last 60 years, it’s Sir Kim Workman. A teenage police recruit in the late 1950s, he saw the downside of the Māori urban migration first hand, including welfare homes and the high number of Māori being funnelled into them. After a stint at the Ombudsman’s office he was head of prisons from 1989 to 1993 and he saw the kids who were in Kohitere Boys Home turn up as angry young men. In the years since he has been a tireless advocate for prison reform.

Those decades of experience ensure a conversation with him is engrossing and digressive, mixing in stats and gossip that are relayed in his rumbling, gravelly voice and with a fair dose of robust Māori humour.

Workman says the way Māori are targeted and treated unequally by state agencies like the police and courts has changed over the decades that he has observed it. From when he was first in the police in the 1950s – there was only one other Māori cop – through to the 70s, such targeting was crude and obvious. Over the years, he says, it has become more sophisticated and harder to detect such explicit examples.

He is now more alarmed at the potential for distortion that technology brings to the question of racism in the targeting of crime. Government agencies are feeding different variables it into computer programs, which will spit out results that are only as good as the assumptions and data they are based on. The intention of the formulas is to predict risk. Individuals and entire families and communities can be targeted for heavier policing and monitoring not just by police but across government departments, creating a feedback loop that puts increased stress and pressure on communities that already carry great burdens. Those communities could end up being predominantly Māori and poor.

Sir Kim Workman

Sir Kim Workman

“That risk management stuff is going to be a huge future issue for a couple of reasons. The expansion of that risk regime has meant that punishment of offenders has extended well beyond the length of their sentence in prison. That’s the first thing. The second thing, which is more insidious, is the use of big data and algorithms to assess risk.”

In 2014 then American Attorney General Eric Holder issued a warning against the technology, that New Zealand may do well to heed. He called for the US Sentencing Commission to study the use of algorithms in crime prevention. “Although these measures were crafted with the best of intentions, I am concerned that they inadvertently undermine our efforts to ensure individualised and equal justice,” he said, adding, “they may exacerbate unwarranted and unjust disparities that are already far too common in our criminal justice system and in our society.”

Workman worries police, Corrections and other government departments using New Zealand’s future computer models could select variables that are potentially flawed and racially biased at the outset. This then generates algorithms that government agencies act on, which end up targeting Māori whether they’ve done anything wrong or not. He says these systems are harder to challenge than bald racism because they have an air of sophistication and legitimacy.

Teresa Aporo first saw the inside of a court when she was six. It was also one of the few times she would see her mother during her childhood after she and her eight siblings were removed by welfare.

“I remember going to the courthouse. We were taken away in a car. We got picked up, taken to the courthouse and we were taken away. We were all taken away. I was six years old when we were first taken into the care of the state. My youngest sister, she was two years old. There was no one telling us as children what was happening, why it was happening. All I remember is us children being taken away, looking back and seeing our mother screaming. Which made us scream.”

At the time her mother was working as a nannie and house-maid for a wealthy farming family. Her father was in hospital with TB and the kids were often left to look after each other.

“Watching our mother cry. She was so brave, she waited for us to come home. She stayed at that house so we’d always have a home to come back to.”

Aporo says she got off lightly compared to her brothers. She went through foster homes and boarding school. They went through welfare homes and Lake Alice psychiatric hospital. Prison followed.

“The day we left it just stays in my mind. I was six, so I remember. My older brothers must remember but they never ever talk about it.”

Reporter Aaron Smale

Photographer Aaron Smale

Editor Veronica Schmidt

Sub-editor Mark Broatch

Graphic design & data visuals Scott Austin

Additional photography Nick Monro

Made possible by the RNZ/NZ On Air Innovation Fund