For decades, parents have fought to be paid for the care they provide their severely disabled grown-up children. Two months ago the existing Funded Family Care scheme was scrapped, but families say even under the new system the real issues remain unresolved and their battle with the government must continue.

By Catherine Hutton

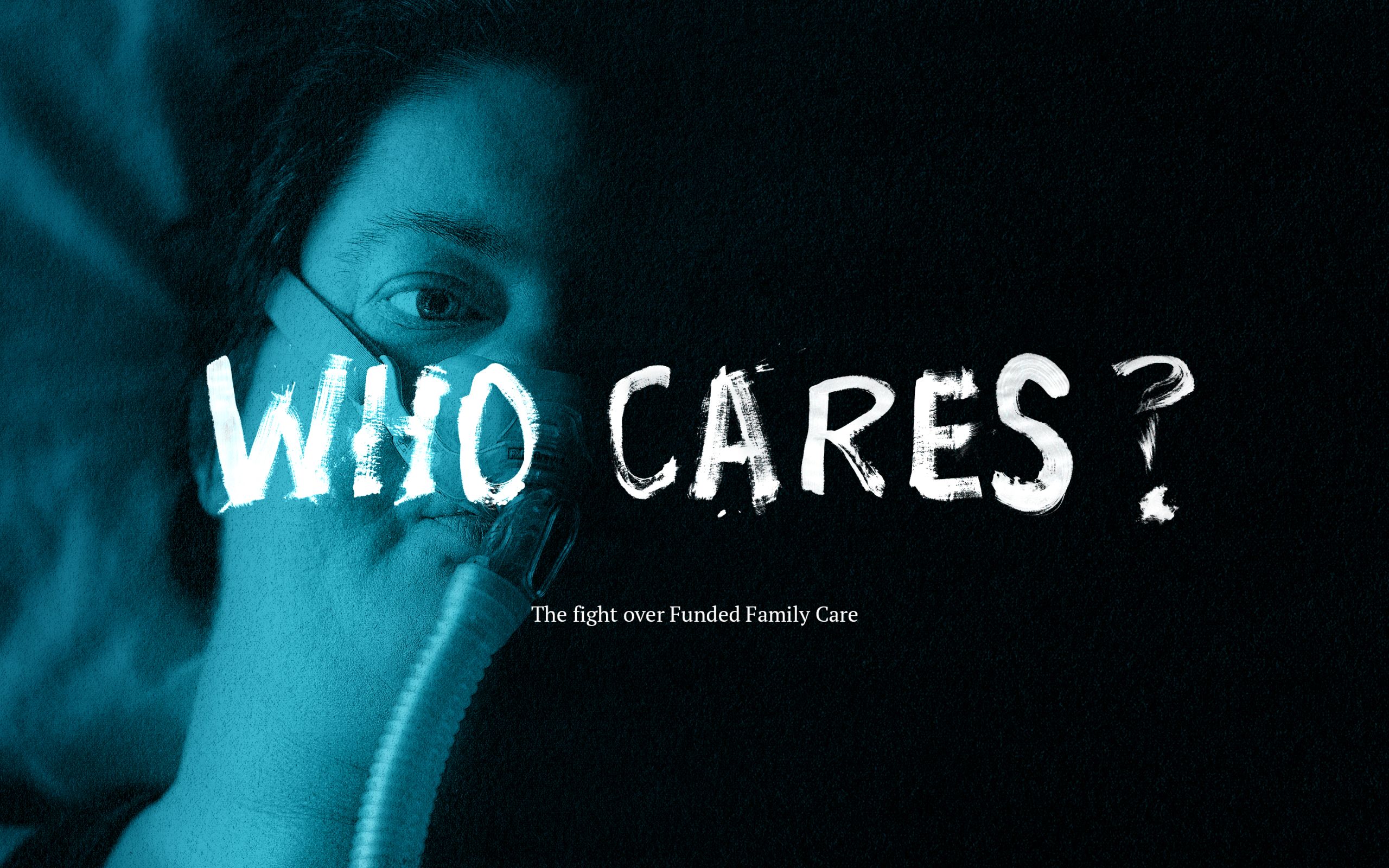

Gilly Hart lies in bed, her beloved dog Piper snuggled into the covers. Behind her, a breathing machine sits on top of a filing cabinet, a black tube snaking down the grey metal to a mask that is a lifeline.

To her left, a cell phone taped to a stick sits within easy reach - another lifeline. The phone is programmed so that with a single touch, Gilly can call Angela.

Angela is Gilly's mum. She is also her employee. Gilly doesn't want to be Angela's boss and Angela doesn't want to be Gilly's employee, but it is September 2019 and the government still insists on the setup under the Ministry of Health’s Funded Family Care (FFC) policy.

FFC was aimed at supporting people with high and very high needs by paying a parent or family member, rather than a third party, to look after them. It created an employer/employee relationship within families.

Gilly, who only has limited use of her left arm and is dealing with many other effects of muscular dystrophy as well as a heart condition, must fulfill the responsibilities of any employer. That means she must take responsibility for Angela's tax, holiday pay, sick pay, annual leave, ACC and KiwiSaver payments.

Yet, she says, she can't call the shots like another employer could; the government does that. Gilly can’t decide how many hours Angela should work, how much Angela is paid or the tasks she can perform.

Gilly, 38, has always lived on borrowed time. She doesn't want to spend any more of it tangled in bureaucratic red tape and getting by on what she says is stingy support.

Although her body is failing her, her gaze remains intense and her mind sharp. Yet getting the right words out can be a struggle. Her sentences are punctuated with pauses and even with a mask, her breathing is laboured. But she is clear on what she believes needs to happen to FFC - it must be scrapped.

Fast forward a year and this will happen and yet much of what disappoints her, and many others who use the scheme, will remain. Why does a system that's supposed to help vulnerable people cause them such distress?

Angela’s short, grey hair and wire-rimmed glasses reflect her straightforward, no-nonsense personality. She doesn't wear a watch, makeup or jewellery, just a cell phone on a cord around her neck. Angela has to be no-nonsense: Gilly is totally reliant on her, needing her for toileting, showering and dressing. Angela is mother, carer, nurse, companion and wheelchair mechanic.

Gilly says the most she can do in their Christchurch kitchen is carefully stir a pot, so she needs to be fed. “It's really difficult to find your mouth under a mask like this with a spoon or a fork. I don't want to get food all over the mask; some parts of it can't get washed readily.”

There's no back-up battery for the ventilator and Gilly cannot remove the mask or sit up by herself. If the power dies for more than two hours, she will suffocate. Angela used to spend every night beside her daughter’s bed, sleeping on a mattress on the floor, but mobile phones changed that and now she only bunks in when Gilly is sick.

Angela administers a dozen different medications a day and is responsible for changing dressings, applying ointments and constantly checking and cleaning Gilly’s breathing mask and feeding tube.

For all this, Gilly employs Angela for 40 hours a week and pays her the minimum wage. The pay is more than the benefit Angela survived on before FFC was introduced in 2013, but Gilly says neither the hours nor the pay rate reflect what her mother does for her.

At least Gilly is able to employ Angela for 40 hours. While FFC was supposed to help the country’s most disabled, of the 447 people who were receiving it a year ago, just over a third (167) received 31-40 hours of paid care a week, and only a dozen people received over 40 hours.

Gilly is at a loss to explain how Angela was allocated 40 hours - the assessment process, she says, is opaque.

Rachel Thaggard’s son Brockton loves watching movies. From the sofa, the 44-year-old gestures with his hands and grunts to alert his visitors to the large television which is playing the 2018 Queen biopic Bohemian Rhapsody - a favourite. He is a large, affectionate man, who likes cuddles and has a huge smile.

Brockton, known as Buzz, has cerebral palsy, epilepsy, and communicates through sounds and gestures. Already unsteady on his feet, a recent sudden onset of gout in his foot has made things worse. He had to miss his weekly music class, where he likes to play the tambourine.

Rachel’s days are consumed with caring for him, in their Auckland home, but FFC only paid her for 27 hours’ work a week.

Rachel and Buzz’s dad broke up in 2005 but she and her ex-husband continue to live together because they can't afford to live apart.

Rachel had to give up her job at AUT and move on to a benefit to care for Buzz, so when FFC came up, she saw it as a better option. She contacted the Ministry of Health’s Needs Assessment and Service Coordination service (NASC), and Buzz was assessed.

There are 12 different NASC providers, with each operating in a different area of the country. NASC assessments are based on a decades-old template designed to assess a person's ability to cope. Buzz, who cannot speak, was asked to identify his goals, priorities and support needs.

Rachel describes the assessment process as "one size fits all," and says it factors in some tasks a carer will need to do, like toileting and washing, but doesn't account for plenty of other jobs. "If he's had an accident in bed - the whole thing has to be stripped … and there have been times I've been washing from morning until night, all day long, when he's had accidents."

Families complain the assessments are exhaustive (lasting up to four hours), unnecessarily intrusive, too prescriptive and don't address the person's actual needs.

Researcher Jo Esplin has studied FFC and says the assessment process didn't work as it was supposed to because the ministry had so many rules, requirements and constraints.

While she believes NASCs around the country try to make the system they have work, families report feeling NASC staff don’t listen to their needs and even say the assessment process harms their wellbeing and lowers their self-esteem.

After Buzz’s assessment, Rachel was allocated 32 hours a week FFC for personal care and household tasks. Rachel challenged the allocation, asking for 40 hours, but she soon discovered it was a frustrating and, ultimately, a futile process. Despite having worked as an personal assistant to four chief executives at the now defunct airline Ansett New Zealand, as well as for the vice chancellor at AUT, she struggled to navigate the system.

The case was peer-reviewed by someone who had never met Buzz, and Rachel’s total hours were reduced from 32 to 22 hours.

She was furious and demanded answers, but says her emails and phone calls to the NASC were ignored. "I was just like, 'What's the culture in that place? Do they care? I mean, they don't even get back to people.'"

Months went by and then the Ministry of Health came back with the offer of 27 hours a week. Rachel, worn down by the process, accepted.

Gilly and Angela’s Christchurch home is littered with medical equipment. Breathing masks are draped over the kitchen bench, wheelchairs are parked in corners, and potions and lotions are clustered on the bedroom table. Despite moving from Auckland two years ago, unpacked boxes still sit in the spare room and pictures remain stacked against the walls.

The house’s clinical feel is disrupted by glimpses of Gilly’s rebellious streak. When they moved in, the bathroom had to be renovated to make it accessible; Gilly insisted it was anything but hospital white, so bright splashes of orange and yellow light up the room.

In here, Angela bathes Gilly. Did her FFC hours cover that? Sort of. Gilly explains: "If Mum puts me in the shower and leaves me in the warm water for a minute or two, which is safe, she technically can't be paid for that unless she immediately gets to work on making my dinner or some other aspect of my care."

That’s because the way FFC hours were calculated and allocated was highly unusual, says independent disability advocate Jane Carrigan. Where other assessments allocate time in half hour blocks, FFC times tasks in minute blocks, she says. The ministry disputes that, saying the assessment process was the same across all Disability Support Services clients.

Carrigan says it asked questions like, how many minutes a day is a carer helping with toileting, with reflux? Carers were only paid for the time they were engaged helping with a physical task, and only for tasks the Ministry of Health defines as personal care or household management - that means supervision and monitoring didn't make the cut, even though it was essential for many people with high and very high needs.

This sticks in the craw of many families, especially as their relatives would be assessed and funded for supervision, day activities, behavioural needs and aspirations, as well as a number of other needs, if they were cared for in group homes or supported living arrangements (options that cost the government about $100,000 per year as opposed to the $36,800 a family carer received for 40 hours of FFC per year).

Carrigan says unbeknown to many families, assessors looked for what they call “met needs”. “They'll ask about the family dynamic, any organisations they belong to, the church they go to, their friends, neighbours, or who might pop in - and people offer this information without realising the assessor treats these people as helping in a voluntary capacity, and attributes them as providing a ‘met need,’” she says.

The assessors also looked at unpaid care provided by other family members and termed it ‘natural support’. It was seen as care that would normally be provided by family and friends so didn’t need to be paid for. Parents complained the term 'natural support' was ridiculous, and say there's nothing natural about the high levels of support their children need.

Some of the information the assessors gathered went into a computer system, via drop-down boxes that limited the information that was collected to determine unmet needs. "They make value judgements about what an unmet need is and there appears to be no consistency in the decision making process. It's a sausage machine," Carrigan says.

The Ministry of Health has faced a raft of legal action over FFC (it has fought three cases all the way to the Court of Appeal and ultimately lost every one, at a cost of at least $2.3 million) and the courts have panned the concept of unmet needs as "artificial" and "invented by the ministry," and have also dismissed the phrase "natural supports" in favour of "disability supports."

In 2016, the ministry revamped the assessment process in an attempt to more accurately reflect the care people received, but Carrigan says the number of support hours allocated didn't increase. The ministry refused to comment on what impact the change had on the number of hours families received.

Carrigan believes when people received low FFC hours, it could have been because the Ministry of Health made a series of value judgments about the amount of help a family needed by asking questions like: Did they own their own home? Were they perceived as coping? Were they married?

She also claims the assessors did not make independent judgements but were “micromanaged” by the ministry.

Put this to Sonia Hawea, the chairperson of the NASC national association, and you’ll get a different story. She disputes the idea the ministry had the final say on the allocation of hours, pointing out the service’s guidelines existed long before FFC was born.

But the Carers Alliance sees the assessment system as problematic, with no way to compare individual FFC packages across the country.

The ministry, which collected data on the number of individuals who received FFC by NASC region and by hours, declined to say if a regional variation existed.

Hawea says assessors used guidelines and peer reviews to achieve consistency and there was some national moderation of allocated hours. She says the service was working with the ministry to come up with a way to achieve national consistency.

Rachel keeps meticulous records and jokes that she had to stay up-to-date with new systems, given she was both Buzz’s employee but also the functional employer. She jokes about what it would be like if she left Buzz to fulfill his role as employer himself. "Oh, look, Brockton hasn't paid me this week - what do I do? I asked him for my wages, but he just pointed me to the DVD player."

Nor could she ask him why he only paid her for 27 hours (though during the Covid 19 lockdown this increased to 40 hours). He couldn’t tell her, and nor, it seems, could anyone else.

As well as chairing the NASC association, Hawea is the chief executive of Taikura Trust, the NASC which was responsible for Buzz’s assessment. Hawea admits the lack of transparency around how the number of FFC hours were allocated was a common complaint. "We aren't going to be able to earn trust and ask people to share with us ... if we're not going to be able to be transparent back. It's a really important principle for me and my team here that we want to be transparent."

So why weren't they transparent?

"Where some of the tools and processes and guidelines happen, we are as transparent as we are able to be with the information that is ours. I believe we are. We aspire to that.. [but] we're nowhere near where we should be as a system that administers the allocation of public funds to support people’s needs. I think we've got a long way to go in that,” Hawea says.

She also admits her staff's caseloads should sit at about 100 but they were ranging between 250 and 380, a situation she describes as "a bit scary” and “unsustainable”.

"When you're trying to make improvements to a system, over the top of an existing system, without really going back to the fundamentals, then it becomes more complex,” she says.

“You get the result that you definitely weren't looking for, which is a more complex system with pockets of opportunity in some areas and other areas that are languishing, waiting for the big change."

People with high and complex needs acting as employers. Funding allocated via assessments families find exhausting and opaque. Tasks counted by the minute. How did it come to this?

The government didn’t want to pay family carers at all. Otago University Law Professor Andrew Geddis says it only introduced FFC because it was sick of losing legal cases. A group of families known as the Atkinson plaintiffs had claimed family status discrimination because the government would pay strangers to care for their family members but wouldn’t pay them. The Ministry of Health, fearing the financial cost of paying family carers could be huge, fought them all the way to the Court of Appeal and lost.

So, in 2013, FFC came screaming into life. The Public Health and Disability Amendment Bill was rushed through Parliament in a single day, with no select committee oversight. The bill was passed under urgency and made New Zealand the third country in the world, behind Sweden and the Netherlands, to pay a wage to some family carers (spouses were excluded). It also effectively ended carers’ ability to take action, under the Human Rights Act, at the Human Rights Commission or the courts.

"In a society where we have rule of law, and the law is meant to dictate how the government acts, that was pretty obnoxious," Geddis says.

But why make disabled people their family members’ employers? Documents show the National-led Cabinet was advised by the Ministry of Health’s then manager of disability policy, Kathryn Brightwell, this was the cheapest option.

"The ministry was not in a position to effectively take on 1600 new employees, and if ... existing contracted service providers had been used as an employer of family carers, the cost of the policy to the ministry would have gone up substantially, by reason of the need to pay overheads and other administrative tasks, as well as training and compliance costs, which are not necessary if the disabled person is the employer," she wrote.

Seven years on, the government’s financial worries never came to fruition. Of the ministry’s Disability Support Services’ $1.4 billion budget, only 1 percent ($13.8 million) was spent on FFC.

In March, only 488 people were receiving FFC through the ministry, well short of the 2013 prediction of 1600. Plans for an FFC advisory group were scrapped in 2016, because uptake was so low.

The Ministry of Health’s take? Some people preferred their own arrangements and didn’t want to change to FFC, some were incapable of caring for their family member, and others didn't want to have to be an employee of their relative.

But Gilly suspects it was because it was a battle to get FFC. "It's almost as if they want people to stay stuck in the poverty trap," she says. Gilly had to establish to the satisfaction of the NASC that FFC was not merely a good option for her, "but that it was the best possible option”, she says.

Indeed, a 2013 document provided to RNZ says families couldn't receive FFC simply because they wanted it. "There have to be existing or new circumstances which are adversely impacting on the disabled person that only funding for their employed family carer(s) can adequately address," the document says.

And if you got FFC, you still had to navigate the scheme - one the courts have continued to criticise. During a 2017 case, that argued carers should be paid for supervision not just personal care and household management, the Court of Appeal urged the Ministry of Health to simplify its policies, describing them as “verging on impenetrable” to the extent that a number of lawyers and judges struggled to decipher them. During the same case, the ministry admitted that having a disabled person who lacked mental capacity acting as an employer was a “mere fiction”.

ALTERNATE REALITY

At Holt House, on Auckland’s North Shore, puzzles and books are stacked on the coffee table and photos of a trip to Australia adorn the walls. It resembles a typical flat, albeit an extremely tidy one, but it’s a group home - one of the alternatives to Funded Family Care.

Five people live here under the care of charitable trust Spectrum Care, which provides support for people with disabilities. The residents take arts and craft classes, walk their dog, go to the gym, and even, occasionally, go hammer throwing. Each resident has their own carer to ferry them to and from activities.

Raphael Kibblewhite, who works part-time at Wendy's, is the most recent arrival and while that means he has the smallest bedroom, he loves the place. "You get up in the morning and there's smiling faces, you go and do heaps of stuff," he says.

Ginny Gislason manages the carers and residents, who pay $300 a week via benefits from the Ministry of Health or Social Development. "We like to have fun here, it's about people making choices, their own choices and about having fun. We try to make it whatever you and I would do."

And she really means whatever you and I would do. Take Ashley Reuben, she says, who uses a wheelchair and is unable to speak, but has completed a tandem skydive.

Another alternative to FFC is supported living. It’s an option Jeffrey Hakanson, 27, who has Downs Syndrome, which includes intellectual impairment, took up eight years ago. He receives about $400 from a supported living payment and leases a 1950s brick and tile house at the end of a cul de sac in Dunedin’s Liberton. Support workers, including psychology graduate Sam Xu, come in to assist him.

Xu says when he started with Jeffrey six years ago, Jeffrey would spend hours playing computer games, but now his confidence has grown and he takes regular trips to the pool, library and Countdown, where they buy Jeffrey’s favourite sausages and pie.

Jeffrey’s mother, Heather, who was originally reticent about the idea of supported living, is now delighted with the progress he has made.

But supported living and residential care providers are under pressure.

One provider says it costs about $100,000 a year to keep someone in residential services, and those with higher and more complex needs can cost up to $580,000. (A 40-hour annual FFC payment was $36,800. Under the new rates the annual cost ranges from $42,640 - $53,040 for a 40-hour week).

Those who work in the system say it's underfunded and isn't keeping pace with demand. Last year, the Disability Support Network calculated the residential system needs an annual cash injection of $574 million to correct a decade of neglect and underfunding.

Spectrum Care chief executive Sean Stowers says the residential care funding model is premised on four to five people living in one home, but there's growing recognition that the fewer people there are in the house, the better the outcome.

Spectrum, which has 440 people in 120 homes across the North Island, says families are becoming more vocal about what they want and it’s not necessarily what is currently available. "There's a move, and it's a move we would support, of people having more choice and control in their own lives, people having control over their funding as well," he says.

Families may want to own or rent the home their disabled family member lives in, they might want a say in the staffing, and may want to be involved in the caring, but in order for them to have that greater flexibility, the ministry needs to make hard choices about who it funds.

Disability Support Network chief executive Garth Bennie says supported living providers and residential providers are propping up an underfunded system.

Residential services haven't had a funding increase in three years, with the exception of increases to meet pay equity costs. "We're just having to continually look at where can we get savings, how we can become more efficient? Is there a better way of working?" Stowers says.

In July last year, at an afternoon tea at Wellington's Premier House for a select group of families with disabled children, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced the government’s new tweaked FFC policy.

Looking over a large table laden with sausage rolls, cut sandwiches and cups of tea, she said she had listened to families who said FFC needed to change and promised "a more compassionate government that addressed the needs of stretched parents and partners".

She vowed to increase the hourly rate from $17.70 to between $20.50-$25.50 and also signalled families’ right to complain to the Human Rights Commission and the courts would be restored.

In January, then associate health minister Jenny Salesa went further, announcing the government would expand the carers covered by FFC to take in spouses, partners and people as young as 16 instead of 18, and those under the age of 18 with high and very high needs would be eligible for FFC. The government also removed the requirement for an employment relationship between family members, “where families don’t want it.” She also reiterated the intention to lift pay rates and restore families' rights to complain to the Human Rights Commission and the courts.

“We know there has been frustration in the disability community with the very limited scheme introduced under the last government, and that's why we have been working with the sector to make Funded Family Care fairer and better for families,” Salesa's press release said.

Ministry of Health’s Deputy Director General for Disability Adri Isbister says removing the obligation on the disabled person to be the employer and restoring families’ rights to appeal created a much fairer system.

In April, as the country grappled with the first wave of Covid-19, the government increased family carers' pay rates and broadened the eligibility criteria. In August, a bill which restored families rights to complain to the Human Rights Commission passed unanimously, under urgency, just before parliament rose for the elections.

Then in May, a bombshell: Almost 500 families received a letter telling them FFC would cease at the end of August, and carers would either be employed by a family member (Individualised Funding or IF) or a service provider (Home and Community Support Services or HCSS). While the government had signalled changes to the scheme, scrapping FFC and forcing families onto one of these options had never been publicly announced. Confusion set in.

The Carers Alliance, which was blindsided by the announcement, fielded hundreds of calls asking for help. Carers wanted to know if the changes meant they would become an employee, a contractor, or were self-employed.

The Alliance was so concerned it commissioned the Alliance's former chair, John Forman, who had received FFC and made the transition to IF, to develop a resource to help carers navigate their options. His conclusion? It was counterproductive to try to interpret the 'slack' information that existed. That, he said, was the officials' job.

The Alliance says things have now settled down and most carers have been shepherded into the new system and are organising their own employment relationships through their family member. But the Alliance maintains the information about options still isn't comprehensive enough for people to exercise choice – particularly for those who are new to the system.

Jane Carrigan is even less impressed. The change many had wished and fought for – the end of FFC – actually changed nothing, she says. "It doesn't change the substance that makes this policy so wrong," she says.

The Minister of Health and the Minister for Disability Issues have spent the last three years swamped by advice and an endless round of meetings considering change, she says. What happens? Literally overnight everyone is transitioned out of FFC into the Ministry of Health's two legacy funding mechanisms, which have both been around for years. Neither of them is purpose built for families, much less new policy.

The ministry is indifferent to the work arrangements imposed on families by the changes, she says. “Your NASC continues to time your bowel movements by the minute, and that will determine how your carer is paid. Where is the victory in that? Respect and dignity for the person with a disability, what a load of rot,” she says.

And she scoffs at the law change restoring families’ right to complain to the Human Rights Commission. Wouldn't it be better to change the system so people don't have anything to complain about, she asks.

Indeed, the changes do not address the assessment process or take into account people’s needs beyond personal care and household management. And the number of hours family carers can be paid a week continues to be capped at 40.

There is still no recognition of the supervision or monitoring carers provide and there remains an on-going reliance on the “natural supports” the courts have rubbished. It continues to affirm the principle that in the funding of support services, families, generally, have primary responsibility for the wellbeing of their family members.

The ministry says to change that principle would require a decision at government level. Jenny Salesa, who was associate health minister until recently, declined to be interviewed for this story.

On the assessment process, the ministry says families who aren’t receiving the hours they think they should, should go back to their NASC (there is no independent review process), but there are no immediate plans for change.

That’s because the ministry is awaiting the outcome of a pilot, Mana Whaikaha, running in the MidCentral region. Instead of NASCs, families have been assigned “connectors” who work alongside a disabled person and their families, including those with high and very high needs, with the aim to give people more choice and control.

The ministry’s Adri Isbister says in the 22 community conversations she has had with disabled people and their families in the past few months, they have overwhelmingly said they would like flexible disability support. The problem is the pilot isn’t due to be evaluated until the end of the year and any decisions are unlikely to be made until mid-2021. What are families to do in the meantime? And why have they had to wait so many years for change?

“I totally acknowledge that government process can take time. However, we’re really, really pleased about the opportunity that we will have with the flexible disability support,” Isbister says. The government is working with the high needs group and by changing the way FFC is administered, it is making it fairer and creating more choice and control, she says.

But many families disagree. Privately, they express their disappointment in the coalition government’s lack of action. It has been three years since the last Court of Appeal case, they say, yet the issues facing family carers remain.

Carrigan questions why the government continues to give the option of having disabled people act as employers, despite the Ministry of Health previously admitting this was “mere fiction”. Later this month, she’s taking legal action, seeking a declaration from the Employment Court over whether people with intellectual disabilities have the mental capacity to be employers.

Isbister says many people with high and very high needs are capable of making employment decisions and there are other options that don’t require the disabled person to be the employer. Yet half of those receiving FFC through the ministry listed intellectual disability as their primary disability, while another 15 percent have some intellectual disability.

While FFC assumed the disabled person was the employer, under IF those who are unable to be an employer can appoint an agent, although it's not clear how someone who lacks mental capacity can make that choice. The ministry doesn’t keep a record of how many agents there are.

Carrigan has reluctantly agreed to be an agent for three people, although she doesn't consider herself an employer and has only agreed to do it so people can get funding.

For that, she files time sheets and does the tax. This time-consuming and unpaid role carries all the legal responsibilities of being an employer. She has to provide the personal details for the “employee” and herself to the third party provider. If the employee doesn't get paid, then it's up to her to sort out the problem. To avoid a fortnightly $45 payroll fee, she opted to do it herself. Yet once when she forgot to attach a time sheet (even though the hours of the employee never change) and she was fined a $45 late fee.

The ministry’s website still does not offer much advice for families or disabled people about the different options or the implications of choosing one over the other. Two days before the deadline for families to make the switch, it issued some documents to families. It’s also providing further information to NASCs so they can help families make these decisions and transition to the new arrangements. But given the whole system is still focused on Covid, carers say it's hard to get traction on anything else.

Carrigan doesn’t think much of the alternative employment arrangements the government is offering. She says they keep families at arm’s length from the ministry.

One solution, she says, is to increase the amount of, and extend the reach of, the existing Carers Support Allowance or allow families and/or individuals who want to make their own choices to have full control over their employment relationship.

As for the increased pay rates, Carrigan describes the criteria around the rates as “typical nonsense”. Carers’ pay rates are based on qualifications and the paid time they have spent in the workforce. Unpaid experience isn't recognised, because parents - who have never been paid - haven’t had continuous employment and therefore can’t receive the top rate. Instead most receive the lowest rate of $20.50 (gross).

Carrigan says there is no one more experienced than the parents of high needs children or adults at looking after their children and their rates should reflect that.

"These people are doing things that service providers won't allow their employees to do. They provide medicine, they feed [via feeding tubes], they give injections and do work substantially more than the narrow list of personal care and household management tasks. These parents are more qualified than some of the GPs and specialists that look after these kids and adults,” she says.

Then there's the pay rates themselves. The ministry pays a third party host to manage the Ministry of Health’s $31.23 an hour for the family carer. They also receive $550 for every new referral and $965 each year for the cost of scrutinising the disabled person's spending. The ministry says this covers the costs of maintaining balances and statements for the disabled person and keeping them informed on information relating to the system. It's unable to provide a breakdown of these figures.

The other option is having a ministry-contracted service provider employ the family member. These providers receive between $33-36 an hour from the ministry. This covers the carers' hourly rate, annual leave, sick leave and ACC levy. But again, the ministry is unable to provide an hourly breakdown.

Carrigan says it appears these service providers receive about $10 an hour, per carer to cover administrative costs and profit margins. The ministry says providers needed to hire coordinators and clinical staff, as well as invest in quality, staff and system development. But it is unable to say how these staff and services will impact on the day-to-day care provided by the family carer.

COURT OUT

A timeline of the decades-long legal battle between the government and parents of high and very high needs children.

2000

Families able to complain to the Human Rights Commission about the government's actions.

Susan Atkinson and eight others complain to the Human Rights Commission about the Ministry of Health's policy of not paying family carers.

2005

The Director of the Office of Human Rights Proceedings takes their case to the Human Rights Review Tribunal.

2007

Margaret Spencer complains to the Human Rights Commission that she is not paid for caring for her son, Paul.

2008

Atkinson hearing before the Human Rights Review Tribunal. Ministry of Health claims the cost of family care policy ranges between $17 million and $593m.

Jan 2010

The Tribunal declares the ministry's refusal to pay family carers of disabled family members is discriminatory and breaches human rights. Despite its own 'no exceptions' policy, it emerges the ministry has paid 272 family members because of either the difficulty of finding carers, rural isolation or cultural reasons.

Sept 2010

The High Court upholds the Tribunal's decision in the Atkinson case.

May 2012

The Court of Appeal upholds the Atkinson decision of the Human Rights Review Tribunal.

May 2013

Government passes NZ Public Health and Disability Amendment Bill under urgency. The Atkinson families are blindsided by the legislation, according to Frances Joychild QC, who represented them.

Oct 2013

FFC comes in, with 1600 people expected to take it up.

July 2016

Spencer is awarded $207,000 in compensation for caring for her son.

2017

Diane Moody challenges the number of FFC hours the ministry has allocated to her son, Shane Chamberlain. She argues the assessment process should include supervision. The High Court dismisses the case.

Moody takes her case to Court of Appeal. Ministry warns paying parents for supervision would change the way disability services are provided and funded, but court finds it would have “a marginal funding impact”. Lawyer Paul Dale QC, who represented Moody, describes the assessment process as “repugnant, absurd and offensive”.

Feb 2018

Moody wins at Court of Appeal, with court urging the ministry to settle its differences with family carers without litigation. It describes the ministry's disability policies as "verging on impenetrable". Ministry responds by preparing “easy read" guidelines.

Sept 2018

Government announces intention to restore families’ rights to complain to the Human Rights Commission and the courts. Lawyer Jim Farmer QC, who represented Spencer, says the government continues to wrongly claim that families caring for their disabled adult children have primary responsibility for the well-being of family members and that this should be the primary responsibility of the state.

July 2019

Government announces changes to FFC, including increasing the hourly pay rate from $17.70 to $20.50-$25.50.

Oct 2019

Independent disability advocate Jane Carrigan files papers with the Employment Court seeking a declaration as to whether those with intellectual disability are capable of being employers. She asks the court to decide, is there an employment relationship and if so, who is the employer and who is the employee?

Jan 2020

Government announces FFC will include spouses and partners as well as parents, allows those under the age of 18 to receive it. It also removes the need for an employment relationship.

Joychild acknowledges the government's situation is complex and difficult but is adamant the "deeply offensive and insulting" assessment system needs to change.

"You've got to have people in there who can and want to give people with disabilities and their families freedom, and really want to comply with the human rights of people with disabilities and their carers," she says.

March 2020

Ministry of Health writes to families to tell them FFC is ending. Disabled people who want to pay a family carer have the option of either Individualised Funding (IF) or contracting through Home and Community Support Services (HCSS). Families must decide by August.

April 2020

Family carers' pay rates increase and eligibility is broadened.

Aug 2020

Government repeals Part 4A of the NZ Public Health and Disability Act 2000.

Sept 2020

FFC ceases

2000

Families able to complain to the Human Rights Commission about the government's actions.

Susan Atkinson and eight others complain to the Human Rights Commission about the Ministry of Health's policy of not paying family carers.

2005

The Director of the Office of Human Rights Proceedings takes their case to the Human Rights Review Tribunal.

2007

Margaret Spencer complains to the Human Rights Commission that she is not paid for caring for her son, Paul.

2008

Atkinson hearing before the Human Rights Review Tribunal. Ministry of Health claims the cost of family care policy ranges between $17 million and $593m.

Jan 2010

The Tribunal declares the ministry's refusal to pay family carers of disabled family members is discriminatory and breaches human rights. Despite its own 'no exceptions' policy, it emerges the ministry has paid 272 family members because of either the difficulty of finding carers, rural isolation or cultural reasons.

Sept 2010

The High Court upholds the Tribunal's decision in the Atkinson case.

May 2012

The Court of Appeal upholds the Atkinson decision of the Human Rights Review Tribunal.

May 2013

Government passes NZ Public Health and Disability Amendment Bill under urgency. The Atkinson families are blindsided by the legislation, according to Frances Joychild QC, who represented them.

Oct 2013

FFC comes in, with 1600 people expected to take it up.

July 2016

Spencer is awarded $207,000 in compensation for caring for her son.

2017

Diane Moody challenges the number of FFC hours the ministry has allocated to her son, Shane Chamberlain. She argues the assessment process should include supervision.The High Court dismisses the case.

Moody takes her case to Court of Appeal. Ministry warns paying parents for supervision would change the way disability services are provided and funded, but court finds it would have “a marginal funding impact”. Lawyer Paul Dale QC, who represented Moody, describes the assessment process as “repugnant, absurd and offensive”.

Feb 2018

Moody wins at Court of Appeal, with court urging the ministry to settle its differences with family carers without litigation. It describes the ministry's disability policies as "verging on impenetrable". Ministry responds by preparing “easy read" guidelines.

Sept 2018

Government announces intention to restore families’ rights to complain to the Human Rights Commission and the courts. Lawyer Jim Farmer QC, who represented Spencer, says the government continues to wrongly claim that families caring for their disabled adult children have primary responsibility for the well-being of family members and that this should be the primary responsibility of the state.

July 2019

Government announces changes to FFC, including increasing the hourly pay rate from $17.70 to $20.50-$25.50.

Oct 2019

Independent disability advocate Jane Carrigan files papers with the Employment Court seeking a declaration. She is asking the court to decide, is there an employment relationship and if so, who is the employer and who is the employee?

Jan 2020

Government announces FFC will include spouses and partners as well as parents, allows those under the age of 18 to receive it. It also removes the need for an employment relationship.

Joychild acknowledges the government's situation is complex and difficult but is adamant the "deeply offensive and insulting" assessment system needs to change.

"You've got to have people in there who can and want to give people with disabilities and their families freedom, and really want to comply with the human rights of people with disabilities and their carers," she says.

March 2020

Ministry of Health writes to families telling them FFC is ending. Disabled people who want to pay a family carer have the option of either Individualised Funding (IF) or contracting through Home and Community Support Services (HCSS). Families must decide by August.

April 2020

Family carers' pay rates increase and eligibility is broadened.

Aug 2020

Government repeals Part 4A of the NZ Public Health and Disability Act 2000.

Sept 2020

FFC ceases

Angela Hart, who has spent night after night on her daughter’s floor, who has bathed Gilly, dressed her, dosed her with medications and changed her dressings, is probably eligible for the top rate. That’s not because of the care she has provided, but because she has a teaching qualification, which, she says, has little relevance in her ability to care for Gilly.

The health and wellbeing qualifications the Ministry of Health refers to are geared towards those who work in retirement and group homes, and those qualifications require sign-off by a registered nurse or supervisor. Angela’s supervisor is Gilly, which means Gilly would be the one signing off her certificate.

"We said to them, 'Look, it's just me and her, what do we do?' and they said, ‘That's fine, she [Gilly] can sign it off,’ which shows how rigorous it is," Angela says.

Without any checks or auditing, Angela says her certificate "is not worth the paper it's written on”.

On 7 February, FFC issues fell down Angela’s list of worries when Gilly was admitted to hospital with heart failure.

Danielle, a Canadian friend Gilly had chatted to online for more than a decade but never met, was already on her way to New Zealand to visit. Gilly, a foodie (at one stage she was one of the top restaurant reviewers in Christchurch on the app Zomato), had planned to take Danielle to her favourite restaurant. Instead the pair, who both love Star Trek, ate takeaway steak and Canterbury lamb in Gilly’s hospital room.

Soon after Danielle left, Gilly’s body began to shut down. In the early hours of 17 February, with her mother and brother at her bedside, Gilly died.

Angela says Gilly was pleased that changes were on the way for FFC, but disappointed that the underlying disability assessment system remained untouched.

Angela, bereft but determined to survive, says she will always remember her daughter as intelligent, kind and honest. “She was a good person,” she says simply.

Gilly’s dog Piper has taken to sleeping on Angela’s bed, but she is out of sorts and mopes around the house.

Gilly was 39.

* Principal Consultant and FFC researcher Jo Esplin, who spoke to RNZ for this story, passed away unexpectedly in July. Her colleagues at Sapere Research Group remembered the work she did to give a voice to many, including those with physical and intellectual disabilities. They noted her empathy and respect enabled her to undertake this sensitive and challenging primary research, in a way very few others could match.

Reporter Catherine Hutton

Executive editor Veronica Schmidt

Videographer & photographer Claire Eastham-Farrelly

Art direction & design Luke McPake

Catherine Hutton was the recipient of the 2019 nib senior health journalism scholarship, which helped fund this project.