A student survives on potatoes and onion. A business owner loses her life’s savings. A minimum wage worker racks up credit card debt. RNZ reporters and photographers chronicle the financial fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic.

It’s cold in the garage at night and there’s only a small lamp to light it, but Josh* sits out here to work so he doesn’t wake his family.

Nights and weekends are the only times he can work now. During the day he’s caring for his three children, while his wife sits at her laptop for many more hours than she’s paid to, trying to save the company she works for. They had a nanny, but there’s no way they can afford her now.

Sending out pitches for business each evening seems pointless sometimes – despite his nightly efforts, Josh hasn’t been hired in months. But what’s he supposed to do? Give up?

Josh waited 10 years to do what he wanted to: quit the corporate world and launch his own business as a consultant. “It was fear of there not being enough work and me not being able to generate enough business.”

Toward the end of last year, he finally felt confident the circumstances were right to gamble his family’s future on self-employment – they had money saved to see them through the quiet summer months, he had a meticulously worked-through business plan and clients in the pipeline.

The business went well at first. So well that Josh and his wife bought a new car on finance and started imagining a move to a bigger house in a more expensive suburb of Auckland.

Then Covid-19 hit. New Zealand closed its borders and the country locked down. Some of his clients deferred the work they’d booked, saying they’d get in touch later in the year. The rest cancelled. It’s been months now since he earned anything and the family is living off his wife’s part-time job.

They’ve taken a six-month mortgage holiday and a car repayment holiday, but what happens when those run out?

Josh has applied for the few jobs that have been advertised in his industry – roles more junior than he would have considered applying for before the pandemic - but was told he was over-qualified. His wife has also tried and failed to pick up more work.

Forget the professional jobs, Josh thought, and he went down to Countdown and asked for work stacking shelves at night, but they weren’t hiring.

So, here he is in the garage, hanging on to hope and pitching for work.

"When you find yourself in a queue to look at the economy cans of beans when you’re used to not even thinking about what you put in the trolley, when you’re accepting donations of four bottles of Heineken over the fence from a neighbour who feels sorry for you... it’s really hard to reconcile with what we felt was in the pipeline for us a few months ago.”

“It is go to work, get the money and that is what you live from.”

“Is it alright for fathers to cry?” Neil Clayton posts on Facebook.

He feels he can’t - not in front of his wife and children. “I tell them everything will be alright”. But he’s been crying in his bedroom.

"I am the breadwinner,” he says. But he hasn't been able to earn since he was locked out of New Zealand by a fatefully-timed March holiday.

Neil emigrated from South Africa in 2019, after more than 15 years of dreaming and planning. He wanted a better, safer life for his children. “I’d heard people walked around – children walked to school! People don’t even have burglar bars on their houses! Don’t have fences!”

He came alone, planning to bring his family over once he gained permanent residency.

A car painter, he landed a job in the Waikato at a Te Awamutu panelbeaters. He bought an old white Nissan Sentra and paid board on a room, but he sent most of the money he earned home to support his family. His wife doesn’t work because she cares for and homeschools their 10-year-old daughter, who has Down syndrome.

Neil missed his family desperately. “It was very lonely for me. All these years being married – 21 years – it's the first time I’d been away.” But he kept telling himself, he was doing it for them, so his daughters, particularly, could eventually have a better life. A safer life.

He saved money to visit them at Christmas, but when it came time to book, he found airfares at that time of year were beyond his budget. Instead he booked for March.

After arriving in Capetown, he had a joyful week with his family before Covid-19 began battering South Africa. The country locked down and closed its borders. New Zealand followed.

Two months later, two closed borders still stand between Neil, his job and his dream for his family.

He's out of money. “I’m not that guy that has big savings. I would say with my capabilities... it is go to work, get the money and that is what you live from.”

In Capetown, everything has shut down and no-one is hiring. The Te Awamutu panelbeaters says they’ll keep Clayton's job open for him until about July, but after that they'll need to rehire.

Will the borders open by then? “You don’t know, I don’t know,” he says, hopelessness tugging his mouth down at the corners. “What can I do?” But he feels it’s up to him to do something. “I’m the breadwinner, I’m the father,” he keeps saying.

“I’m spiritual and that’s the only hope I’ve got – I pray a lot.”

"They were like, ‘We’ll get married eventually but definitely not this year’.”

The garment bags are packed in tighter than usual in the storage room at Hera Couture. Many of them contain wedding dresses designed for nuptials that were scuppered by Covid-19. Some of the brides have lost their jobs now and don't know when they’ll be able to afford to reschedule their weddings.

The label’s owner and designer, Katie Yeung, takes their calls, empathises and tells each one to pick up their gowns and pay when they’re ready.

“I think about 15 to 16 brides of our brides were from Bauer Media,” she says. The magazine publisher folded its New Zealand operation a week into the lockdown. “It was really, really, really sad to see. They were like, ‘We’ll get married eventually but definitely not this year’.”

Katie’s calendar shows months of cancelled consultations the lockdown prevented her keeping - and charging for. Still, she supported the government’s decision to move the country to level 4 and doesn’t blame it for the financial hit her business has taken. It’s the worldwide nature of the pandemic that has really stung, she says.

Hera Couture is sold around the world. But as Covid-19 spread and successive countries locked down, stockist after stockist closed and orders dried up. Hera Couture’s costs continued – in New Zealand, the rental on her K’ Rd showroom, her staff’s wages – and abroad bigger expenses – contracts in China, Australia, the US and UK. “The amount of money that goes out – I was like, ‘we’re bleeding here!’”

She and her husband went over the label's finances with their accountant, regretfully made some staff redundant, and poured their life savings into Hera Couture to keep it afloat.

“I had about three weeks where I couldn’t sleep and then would have constant nightmares about it all,” she says.

Then Germany’s lockdown eased and orders started coming in, new enquiries arrived from stockists in the US and shipping options opened up again. The New Zealand business is recovering too - she’s fully booked for consultations at the K’Rd showroom.

She's back, just minus her life savings. But, Katie says, she could have lost more. “I would have remortgaged the house if it had come to that. I couldn’t let the business die like that – I've worked too hard for it.”

“Nobody has felt like they can say anything because we’re all so desperate to keep our jobs.”

Jane* pulls into Mitre 10, parks her car in the empty lot, and joins a line of her co-workers queuing to be let in.

When she reaches the front, someone aims a temperature scanner at her forehead and it bleeps as it gives a reading: normal. She washes her hands, scans her finger to log in for the day, sanitises her hands again.

There are finally customers to interact with again - her favourite part of the job. For the length of level 3 there weren’t even workmates in close quarters – instead they all kept their distance as they gathered items for click-and-collect orders.

She’s only getting 80 percent of her normal pay, which was already minimum wage. At least she’s back to full-time - at level 3 it was 30 hours.

Eighty percent of the minimum wage nets her just over $500 a week after tax. It’s less than the wage subsidy she was receiving “sitting on her tush” at home during level 4 - and now she has to pay for petrol to get to work.

“Nobody has felt like they can say anything because we’re all so desperate to keep our jobs.”

Even before her hours and pay were cut Jane relied on her credit card to get her through. “A lot of the time it’s the only way to stay afloat … because the retail industry does not pay well.” She normally pays $100 off her Visa bill a week but has had to halve that. Now the balance - and the interest - is mounting.

At the supermarket it’s budget-brand everything - and sometimes not even that. “It’s like: ‘Can’t have that, can’t have that, not this week.’ So they stay on the grocery list and then we see what it’s like next week - ‘Okay, maybe not this week either.’”

Jane can only manage another couple of weeks like this. “It’s starting to bite.”

She had been “dead keen” to help get the company going again, but at the moment it feels like it’s the workers who pay. “It makes people a little bitter.”

“It was definitely one of the hardest decisions I’ve ever had to make.”

On Sunday mornings, the queues could sometimes stretch from the cash register past the cabinets, full of stuffed aubergines and orzo salad, falafel fritters and caramel slice, towards the drinks refrigerator by the front door. Tired looking parents would cling to coffee cups as their toddlers pulled wooden trucks and blocks out of the toy box, while locals, kitted out in walking gear, would slide into tables on the cobblestones out front, tying their dogs to the railing before getting stuck into the weekend paper.

The sign is all that’s left now - elegant black lettering on white, a whisk woven cleverly into the design. ‘Park Rd Kitchen', it announces to traffic heading towards west Auckland’s Titirangi Beach, but beneath the sign the windows are dark.

Soon after the country moved to level 3, owner Pien Wise pulled the plug on the cafe she’d poured so much into for three years. “It was definitely one of the hardest decisions I’ve ever had to make,” she says. But she’d done the maths, turned over the economic predictions and weighed up the government assistance available and all she could see ahead was struggle. “I made the hard call to pull out early rather than keep pouring money into it.”

She’d already lost plenty. When the lockdown was announced, she had a café full of food that would never last until she could open again – whenever that was. She gave away thousands worth of eggs and milk, coffee and slices, flour and sugar, meal ingredients and mixes, aioli and chutneys to her staff and the café's social media followers.

She claimed the government’s wage subsidy, but topping up her staff’s pay to 80 percent cost $4000 in the first month. The rent on the empty café cost $2200 a week. “And then you’ve got all of your other costs as well. It's quite a lot of pressure to contend with.”

Pien kept waiting for the government to offer further help for businesses. When it announced loan options, she was disappointed. “That's really risky, in my opinion, because when you're trading in a business that's all about high turnover and slim margins, you have to be able to pay that money back... And when you start trading again, the economy is not going to be running like it was.”

So Park Rd Café is gone. Seven full time staff – and more casuals - have lost their jobs. Pien is yet to shake the shadow of hers. To-do lists keep tugging at her mind - things she must organise for the café, for the staff - then she remembers, she doesn’t have a business anymore.

“A film makeup artist? That set of skills is not transferable.”

Hannah Wilson has given up on the gardening, sewing and making art that kept her busy in the early days at home, and is sitting in her animal print dressing gown watching TV. She’ll probably sit here like this until dinner time.

She’s six months’ pregnant but she hadn’t planned a relaxing third trimester. “It was a joke that I was going to work until the baby dropped, basically, because I wanted to save money. I don’t know what sort of baby I’m going to have and when I’m going to feel comfortable going back to work.”

Hannah is a self-employed makeup artist in the film industry. She was working on a series starring two English actors when the country went into lockdown. Her cosmetics and brushes are still in the makeup truck at a West Auckland studio. The series’ stars are back in Britain and nobody knows when the New Zealand border rules will be relaxed and they can return. Until then, the production remains in limbo.

Hannah is spending a lot of time on the phone to friends who also work job-to-job in the film industry. None of them have heard of any new shows or films looking for crews. “There’s a lot of joking about going on the dole, which we always joke about between jobs, but this time it’s not so funny... Most of us have been doing this our whole adult careers – I don’t know how to do anything else. And a film makeup artist? That set of skills is not transferable.”

Six months ago, Hannah’s husband changed careers and his earnings dropped. Covid-19 reduced his salary further. When his work shut down, he initially received 80 percent of his salary, but then it dropped to the government wage subsidy of $585 a week.

If you’d told Hannah six months ago that the couple’s long-running, “ruthless” savings campaign wouldn’t get her all the time off with her baby that she’d planned, or the holiday she’d dreamed of for her expanded family, she might have been furious. But she’s seen the pandemic cause so much pain to so many that her own seems minor. “I feel like a wanker for even mentioning it,” she says.

So, she’ll simply go back to work when she needs to, probably earlier than she’d hoped for. She just needs work to go back to.

At her family farm in Arahura, near Hokitika, dressed in a damp, olive-green Swanndri, Charlotte has just come inside after doing some “chook administration”.

Six months ago she packed up her city life in Australia, taking long-term leave from her job as a senior health worker, to start a new chapter back home in New Zealand on the road as a tour guide.

Her old job involved pacing hospital corridors helping people through their darkest days. The new plan was to guide people through some of their happiest. She taught herself how to back a bus with a luggage-laden trailer and started her dream job with Haka Tours. But in March things began to unravel.

“The tour group that I was taking was coming in from overseas, they were on the plane before the lockdown decision was made, then my work confirmed that, ‘No, you won't be guiding. With the latest updates, we've had to cancel that tour’.”

Her final job ended in Auckland. Desperate to get home to Arahura ahead of the looming lockdown, she spotted a car on the side of the road in Rodney with a sign in the window: ‘$1000 ono’. She bought it and drove straight home. “I call him [the car] Phil Miller, after The Last Man on Earth series on Netflix where, you know, a virus takes over the world and kills everybody. He cost me about $300 in petrol and he smells like he’s gonna light on fire any minute.”

Now Charlotte is living on the government’s wage subsidy. All of her clients are international visitors, so there’s no chance she’ll be back at work until the borders re-open. But she’s less concerned for herself than she is for the smaller operators she’s used to visiting while on the road. Thinking of them makes her sad.

“When you're a tour guide, the different lodges and hostels, and the businesses that you take the manuhiri (visitors) to, you're essentially forming an on the road family. And [to know how much they will be struggling,] it's quite sad.”

For now, she’s restoring the family farm’s old shearing sheds, trying to turn them into a tourist venture for an industry with an uncertain future. While she sands, saws and hammers away, she wonders when she’ll be able to ditch ‘Phil Miller’ and get back behind the wheel of her bus to spin yarns with tourists.

“Houses that were renting for maybe $600 a night were now renting for $400 a week…”

At the top of a pebbled trail winding up Coronet Peak, Bridget Murphy catches her breath, lying her mountain bike down so she can take a photo.

The view up here is vast. Blue skies and scalloped clouds stretch away to white-capped mountains, their olive flanks sloping precipitously down to the shores of Lake Wakatipu.

It’s no wonder that 3 million people come here every year. Or, at least, they used to come.

Now, this could be Queenstown before AJ Hackett, before the Shotover Jet, before even the ski fields that attracted the first local visitors.

Houses are dotted here and there on the yellow plains below Bridget, nestled among shelter belts of poplars. How many of them are now empty? She and her husband Aaron own five Airbnb properties in Queenstown and manage and clean another 20. Just two still have people staying in them - American tourists who opted to wait out coronavirus at the bottom of the world.

Things started “dying a death” in February, when New Zealand closed its borders to China. That would normally be the Murphys’ biggest month, with back-to-back bookings. Instead, their occupancy halved.

Then the government announced a full lockdown, and the couple lost $100,000 of bookings in two days.

Bridget recalls the chaos as every Airbnb owner in Queenstown attempted to switch to long-term tenants.

“Houses that were renting for maybe $600 a night were now renting for $400 a week… It was quite cut-throat out there.”

Some long-term tenants - many of them low-paid hospitality and tourism staff - broke their leases to move somewhere cheaper. Others, now out of work, simply left town. “People were just walking out and leaving the keys on the bench.”

Bridget and Aaron count themselves lucky. Their savings will keep their heads above water for a few more months while they wait and hope for the domestic tourists, at least, to come back.

Even their two kids know the distinctive ‘bing’ that sounds on Bridget’s phone whenever a new booking comes through. “When we hear it we all jump around the lounge.”

The days of relying on Airbnb are over, though, and she’s scheming ways to diversify, wishing she’d done so before. “I put all my eggs in one basket.”

“To have nothing, to live on pipi soup with three children. I’ve been there, I’ve done that.”

Ray Chapman stands in her back garden in Auckland’s West Harbour and looks across the silty water of the upper Waitematā, where twice a day the tide surges across the mudflats.

Her partner Willy is out there somewhere - he went back to work at level 3, a boat engineer and skipper on a dredger.

Ray gets up with him at 6 o’clock each morning - the first two awake in a household of seven - but unlike Willy, she doesn’t have anywhere to go.

For the last year Ray has been enrolled at a training centre in Henderson, studying for a certificate in social and community services. She wants to work in mental health, has done it tough herself her whole life; abused as a child, time in prison, two suicides in the family.

It’s in her heart to do this job, she says.

“I just know how that feels for another person… to have nothing, to live on pipi soup with three children. I’ve been there, I’ve done that.”

She took out a student loan to cover the $6000 in course fees, did all the assessments, completed 280 of the 355 practicum hours she needs to pass.

Then the lockdown was announced. Te Whanau O Waipareira in Henderson, the service where she’d been completing her hours, had to close down most of its work. You can’t come in, they told her. We’re really sorry.

She understands, she says. The lockdown “had to happen”. But she wants to graduate and she’s so close. “I’ve got this far and I’ve come to a halt.”

She and the other students have written to their provider, asking if they can still get their certificate with reduced hours. The answer so far is no, although they have an indefinite extension.

In the meantime, she can’t do her hours, and if she can’t do her hours she can’t get her certificate, and if she can’t get her certificate she can’t get work - or not the work she so badly wants.

“I’m 60… Time’s going fast and I want to give what I have - my knowledge and everything in my heart - to my people, to help them. And it’s just very frustrating because I can’t do anything.”

Arihia Bennett takes off her CEO hat and slips outside to be a sister. “Can you turn the lawn mower off? I’ve got someone ringing me,” she says.

Then she’s CEO again - chief executive of Ngāi Tahu. The ‘lawn’ her brother is mowing is the 10 acre block at the rūnanga marae, the papatupu, or ancestral land, in Rangiora north of Christchurch.

The machine dies and now the only sound left is the occasional ping of emails arriving. Sometimes the ping announces that entire livelihoods are gone, or at least frozen. ‘Hibernation’ is the word the iwi is using for parts of its tourism business, victims of the virus.

During lockdown Arihia was in a bubble of seven in a three-generation whare. She’s worn the daughter hat (her elderly father has been unwell) and the teacher hat too (the teenage nephews were doing school work. Allegedly.)

Ping. Swap the CEO hat for the wife hat. “My husband has just got in touch saying he is probably going to be laid off. He was pretty distressed.”

Actually, the counsellor hat is a better fit. “I’m just trying to calm him a little bit. This is all part of the way the world is changing around us. We just have to be grateful to live in Aotearoa and have an abundance of people around us who care.”

And there’s lots of that. Whanaungatanga. Manaakitanga. Kai. Koro and the moko doing karakia, talking about the old ways, growing up on the East Coast. “Often he tells us the same thing over and over, but sometimes there’s a new gem.”

Ping. 300 jobs to go at Ngāi Tahu. All that pain. The tribe that turned $170 million into $1 billion by investing in farming, property, seafood, and tourism. Ping. Gone. Not all of it. Not forever. Hibernating, until after the virus.

“I have just sent out the email now to all of the staff and it's very difficult and very sad.” Ping. “We just can’t keep them on in that hibernating phase.”

But there are lessons from the past and hope for the future.

“I think about our people over the generations and how they have suffered. You just have to find that sense of resilience to bounce back.”

“I’m getting really tired and frustrated, and very anxious.”

Clafi Colaco had big plans for this year. She hoped to expand the cleaning business she had started part-time back when the youngest of her three children, who is now 8, was in preschool.

Before the pandemic came to New Zealand, the 45-year-old, whose friends call her Peppy, was up every morning by 5am to make her kids’ lunches and iron their uniforms. She was on the road by 7am to get to the first of many jobs scrubbing and polishing other peoples’ homes, in the leafy suburbs of central Auckland, until they were sparkling clean. Depending on the day of the week, she would do between four and five houses, alongside the two women she employs, before heading back to West Auckland in time to pick up her kids from school. She works hard so they can have everything they need to excel.

Now, after lockdown, work is coming back in dribs and drabs, but she’s certain not all of her 35 clients will keep her on. No one has cancelled yet - some even called her during lockdown to see how she was. But Peppy knows that if a person loses their income, the cost of a house cleaner will be one of the first to be cut.

These are hard times; Peppy’s household budget is tight. After groceries, there is no money to save, no chance of expanding the business and for now, her children won’t be going back to music and swimming lessons.

Peppy tries not to show her emotions in front of her kids, but her voice is shaky. “I’m uncertain about the future. Mentally - I’m getting really tired and frustrated, and very anxious. I’ve always been a busy person. It’s hard sometimes. I had very high hopes of myself. Because my kids are becoming big, and I said to myself, ‘This year I am going to start a very strong year.’ But it ended up very different for me. I never expected this to happen.”

“I completely understand what New Zealand’s done... but it’s left some people a little bit stuck.”

The buds are appearing in Barbara Hilden’s garden, announcing the beginning of a Canadian spring she never expected to see. She should be amongst the oranges, reds and browns of a New Plymouth autumn, starting a new job at the Puke Ariki museum and a new life in New Zealand.

But here she is in an empty bungalow in Edmonton, Alberta, the sound of her voice, tight with worry, echoing off the wooden floors and bare walls.

The museum curator and her partner are living out of two suitcases and sleeping on a mattress on the floor. Everything else they own is aboard a container ship on the Pacific ocean.

“It could be worse - we’re together, we’re safe, we’re healthy,” she says. But she’s spending the days refreshing the Immigration New Zealand website and the nights lying awake.

After falling in love with New Zealand during a 2019 holiday, Barbara and her partner decided to emigrate and she was delighted when, at Christmas, she was offered a job at Puke Ariki.

Her work visa came through on 15 March, and having had months to plan, she and her partner acted quickly, quitting their jobs, spending thousands on airline tickets, thousands again to ship the contents of their house across the world, and yet more money to rent a New Plymouth house. Four days later the prime minister closed New Zealand’s borders to everyone except citizens and permanent residents. “I completely understand what New Zealand’s done... but it’s left some people a little bit stuck,” she says.

Having quit their jobs, Barbara and her partner don't qualify for unemployment benefits, insurance or any of the Covid-19 help the Canadian government is offering. They’re living on savings and hope.

Around them, museums are laying off staff so Hilden knows if she can’t get to New Zealand soon, she’ll be job hunting against the odds.

"It would be a matter of being a grocery store clerk, and with a masters degree and many years of experience, it’s not where I imagined myself to be at this point in my life.”

“He painted quite a doom and gloom picture.”

The elegant, meticulously hand-drawn plans that Sharon Jansen is hovering over are not the ones she’d expected to be working on at this time. Right now, the Wellington architect is stringing together small bits and pieces to make ends meet. She was supposed to be in the midst of a months-long job.

The financial strife hit the sole-practitioner before Covid-19 really appeared on her radar. Back before border closures and talk of quarantine and alert levels began, one of her clients cancelled because of the pandemic.

Sharon had just returned from holiday, intending to dig straight into the work, so the cancellation came as a shock.

The job - an extension to a guest house in the Marlborough Sounds, whose clientele was mainly from Europe and north America - was a big one. At the time, the reason for the cancellation surprised her. But the owner had lived in Hong Kong during the SARS outbreak. “He had a very good idea of what was about to happen,” Sharon says. “He painted quite a doom and gloom picture.”

Losing the job was a blow and she gave herself a 50 percent pay cut. But four new, smaller jobs have emerged from lockdown to keep her going; former clients who decided to go ahead with renovations after being stuck inside for weeks on end.

Little jobs are more time consuming, and less profitable. But Sharon enjoys them, and she’s counting on them to see her through.

“There are a lot of other small, solo practitioners across the country who will find that the work might just pick up again,” she says. “It might be in a very slow and small way, but it will be there.”

“You don’t think when you’re sleeping.”

Harjeet’s* voice is listless as he describes what remains in one of the two food boxes he’s received from Civil Defence in the last seven weeks. “I have the basics: sugar, onion, potato, salt.” He’s too ashamed to ask for a third box. “It’s like begging for help when you have two arms, two legs, and you can work. But unfortunately in this situation, I cannot work.”

Harjeet is tired and depressed. He says it doesn’t matter that he’s almost out of food, because he’s lost his appetite. He spends most of his time sleeping. “You don’t think when you’re sleeping,” he says.

“But when you’re awake, your mind starts to think a lot of things and it’s bad for health - mental and physical. I try to tell myself it’s going to be over soon. But it’s not over yet.”

He had just finished a year of postgraduate study when the lockdown began. As an international student, he worked part time to get by - as a security guard, or in orchards, just whatever he could get. When his study ended, so did his visa. He says he applied for a post-study work visa before the pandemic response kicked in, but then Immigration New Zealand closed its processing offices. While he waits, he cannot work.

His bills are mounting - rent, internet. Despites his pleas, his electricity provider is threatening to cut the power supply to his Rotorua flat. Because he is not a permanent resident, he doesn’t qualify for financial assistance. His bank account is empty. All he can do is wait for his visa, and then, when it arrives, hope to find work during this impossible time.

While Harjeet waits, he will continue to sleep. “I just close my eyes and lie down on my bed and that’s it. I have to pass the day, I have to pass the week. I have to pass the - don’t know how many weeks more. I don’t know.”

“I watch the briefing every single day, and wait for any announcement about what's next and how I need to change things.”

Jo Freeman’s warehouse would usually be alive with the hum of massive industrial chillers, but for now they are silent; she’s had to turn most of them off to save power. Her ice-making business, which sells to restaurants and bars, is almost completely shut down. She doesn’t know when it will re-open, possibly not until the tourism industry begins to buzz again.

Jo’s other business, Urban Harvest, which delivers supplies like fruit and milk to office buildings, looked like it would go the same way when the lockdown was announced. But as lockdown rules about what could and couldn’t open became clearer, she was relieved to discover she could do home deliveries. It meant transforming Urban Harvest overnight.

“I made a decision on the Thursday, [before lockdown], I sent a survey out to my existing corporate customers… We got a great response back and that night I changed the website. The next day, we opened up to orders and we started delivering on the Monday.”

Jo now delivers fruit, vegetables, milk and eggs to people’s homes. It’s been like starting an entirely new business from scratch, she says.

“The hardest thing has been finding the staff, a lot of my staff are students and they left town before the lockdown [to go back to family]. So I had to scramble around the first couple of weeks to try and find people, in some cases I had family members, I roped in my teenage daughters, my husband's been helping. I have a staff member who got his father and girlfriend to come and help.”

The move hasn’t been hugely profitable, but she has received a rent holiday and the wage subsidy. That help meant she could hang in there enough to keep on all 13 of her staff from across both businesses, albeit at reduced hours.

The strain of trying to stay afloat is immense and Jo lies awake at night worrying about how she’ll keep things going.

“The uncertainty is unsettling. And not knowing what's next and not knowing how many of my corporate customers are going to come back and not knowing if the demand is going to continue. So I watch the briefing every single day, and wait for any announcement about what's next and how I need to change things, because you have to change really, really quickly.”

Mark Stern stands up, clippers in hand, and stretches, in one of the alleyways of yellowing vines that slopes gently down to the Wanaka lakefront.

His back aches. So do his knees.

He’s got more stamina than when he started a week ago, but Mark is six feet tall and most of the grape bunches he’s picking are below waist height. “You’re either kneeling and sort of shuffling along the ground or you’re bending over.”

It’s good to have something to do, though. Early each morning he cycles along the quiet road encircling the lake to Rippon Winery, where he spent the summer running tastings at the cellar door - until the borders closed and the tourists disappeared.

This wasn’t the plan, exactly.

A Glaswegian, he and his Kiwi partner Claire Davis arrived from Scotland last August and moved in with Claire’s parents in Wanaka - temporarily, they thought.

By now, they should’ve been in Dunedin, where Mark had a history PhD lined up: proposal accepted, enthusiastic supervisor arranged, with just the funding still to finalise.

First the cellar door work dried up. Then a few weeks into lockdown his supervisor called with more bad news: his main application for funding had been turned down and the back-up options had vanished, citing the financial uncertainty of Covid-19.

The doctorate - which proposed research in both New Zealand and Scotland - would have been a “neat synthesis” of Mark’s personal and professional life.

“I hadn’t realised how much of a solid sense of my future was baked into doing the PhD.”

Instead he has a few weeks’ work helping with the end of the grape harvest, and a month or so left of the wage subsidy beyond that.

And then? The couple’s best back-up is to move to Wellington. There, Claire can keep working for the publishing business she runs with her sister, and Mark can look for a job - though visa issues make even that plan uncertain.

It’s a bad time to be caught in-between - “and we are very much in-between”.

Mark bends back down, clips another bunch of grapes, and shuffles along the row.

“You’d see people wander past and peer through the windows longingly as if this was from some forgotten time.”

Matthew Crawley’s work is the world of noise. Noise and people and music. He runs a record shop called Flying Out Records and he’s a gig promoter.

His pre-Covid-19 work day would make Ashley Bloomfield frown; large crowds. Music venues. Driving bands around.

Now things are measured by their absence. “This weekend was going to be one of the biggest shows I’d ever worked on but obviously it didn’t happen.”

He’d lined up a US indie band for Auckland’s Power Station and Wellington’s San Fran, but with strong support acts it was more like a mini-music festival across two cities. “It was taking it to that next level of dreaming big about what’s possible for gigs. It turns out the word possible was a really important one,” he laughs.

Now, instead of promoting live music and making money from it, he’s trying to save live music by raising money for it.

He’s just helped launch Save Our Venues NZ, to raise funds via Boosted and Givealittle campaigns for live music spaces devastated by border closures, the lockdown and, now, crowd limits.

But it’s a big fight - San Fran had 80 cancellations in just three days in March and the Power Station says it could be closed for four months - so the campaign needs to raise $500,000 to help dozens of venues across New Zealand.

Matthew, however, is hopeful. Already the campaign has netted $100,000 in donations that will go to Auckland’s Whammy Bar and the Wine Cellar, which both sit empty a short skulk from Flying Out.

Of course, it’s not just the venues that are suffering. The music promotion side of Matthew’s business has dried up. But at least the record shop, on Pitt St just off Karangahape Road, is open again. Click-and-collect wasn’t the same. “You’d see people wander past and peer through the windows longingly as if this was from some forgotten time.”

Now he’s waiting for the fizz of live music to return. By the time it does he’ll have a new skill, after learning to play the banjo during the lockdown. “It seemed like a good instrument for the apocalypse.”

“The Zoom call was pretty brief.”

Emma Clifton is strangely relieved now that the worst has happened.

A week into lockdown, she got the all staff text message calling a Zoom meeting. Until then, she and her colleagues had heard nothing from Bauer, the German company that owned the lion’s share of New Zealand’s magazines, including the one she worked for.

“The Zoom call was pretty brief. Maybe three minutes in we got told that they were shutting the New Zealand company down.”

It was effective immediately, 237 jobs down the drain.

Emma was proud of her career working at magazines edited by women, for women, telling women’s stories. It started 13 years ago when, fresh out of university, she took a job sub editing the New Zealand Woman’s Weekly. She was deputy editor at the Australian Woman’s Weekly by the end.

Over those years she did so much - went to Iran and India, interviewed Jacinda Ardern five times, wrote a book with Rachel Hunter and spoke to survivors of the 2019 Christchurch terror attacks.

But here she is now, calm, curled up on a floral couch at her Auckland flat, sipping tea from an oversized mug emblazoned with a large ‘E’ and multicoloured stars.

Having started her career in 2007, the year before the Global Financial Crisis hit, she says she’s never really felt secure. “I have, for the majority of my career, expected to be made redundant.”

Now that the worst has happened, the dread has gone. It was the days leading up to redundancy that were the hardest - feeling it coming, while working on stories for a magazine that she suspected - rightly - would never be published.

“From people who I’ve spoken to, who are still in the industry, who have watched redundancies happen around them, I feel like that’s a really hard position to be in. Because if your greatest work fear is losing your job, well that’s happened to us. So that fear is now gone. But if you’re still waiting, and you have the sword of Damocles dangling over you, that’s what I struggle with the most - and I think a lot of people are still in that position.”

Emma says she is fortunate to have received a pay out, and has picked up two small, short-term contracts to tide her over. She feels lucky that she doesn’t have children to look after, or a mortgage to pay (though this is, in part, because the nature of the work meant she never felt secure enough to buy a house,) and that her boyfriend has a good job.

Will her pragmatism last, or has reality just not hit yet? “We’ll see in six months from now how worried I am.”

*Names have been changed

Reporting and writing Teresa Cowie, Guyon Espiner, Kate Newton, Veronica Schmidt and Susan Strongman

Executive editor Veronica Schmidt

Photography Claire Eastham-Farrelly with Dan Cook, Nate McKinnon, Samuel Rillstone and Dom Thomas

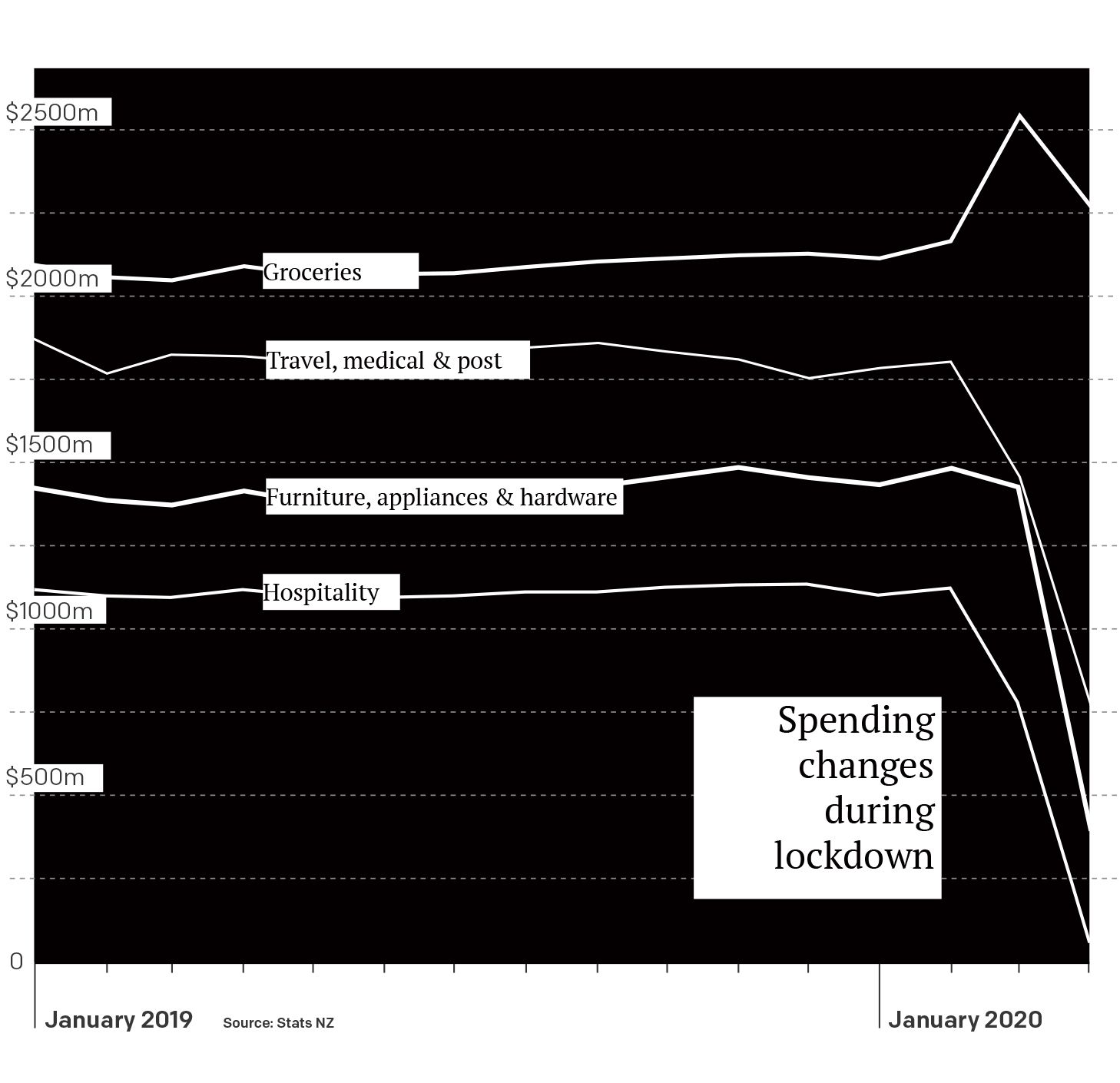

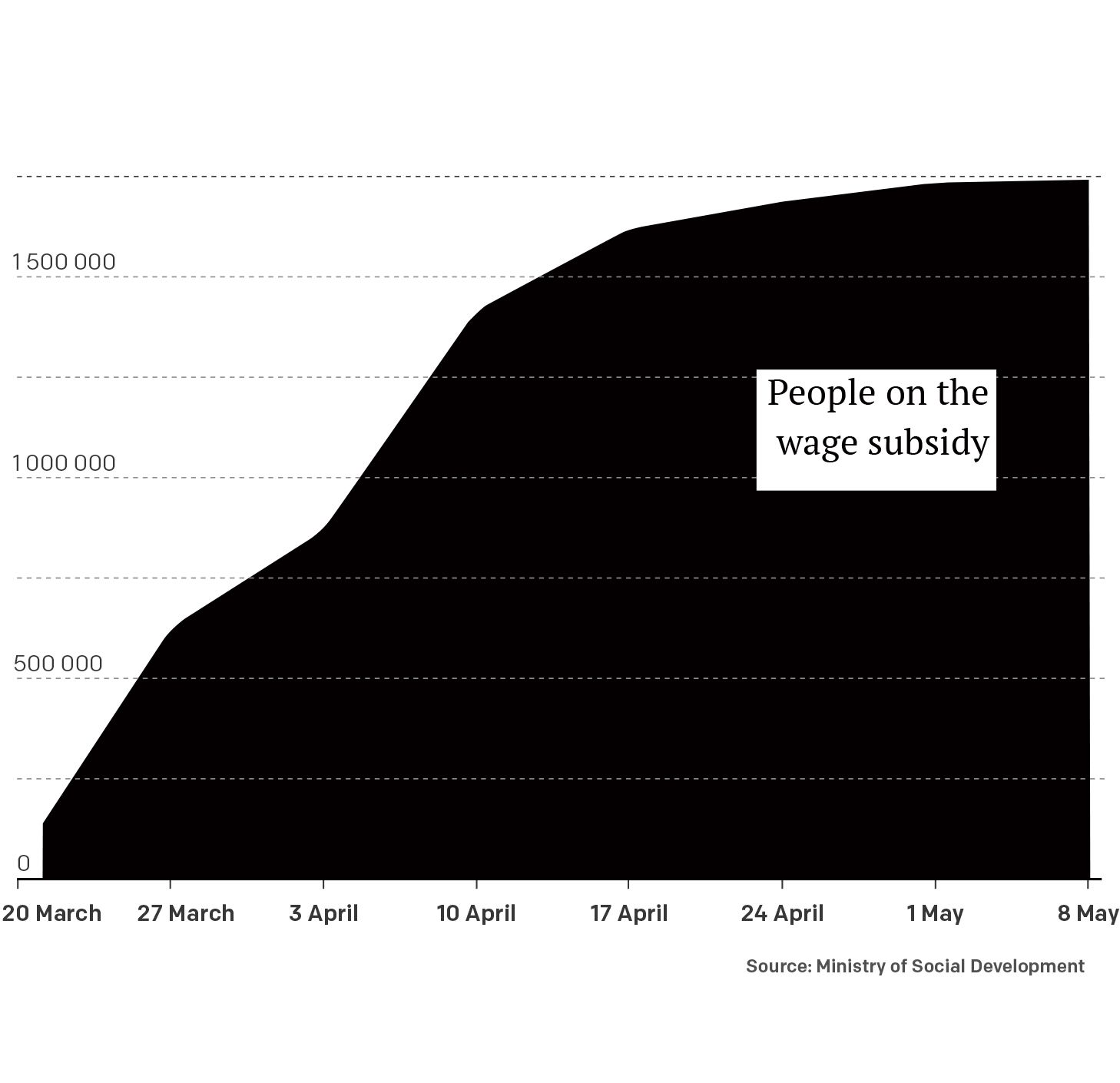

Data visualisations Kate Newton

Art direction, animation & design Luke McPake