A love of nature is embedded deep within our concept of “New Zealand-ness”. But the rich diversity of what we describe as ‘nature’ is narrowing all the time. In a two-part investigation, Farah Hancock reports on Aotearoa’s vanishing species.

Photo / Carey Knox

Photo / Carey Knox

At first, all Carey Knox sees is blackness. An endless vista of charred snow tussock, soot and debris.

As he crunches through the remains of Te Papanui Conservation Park, the blackness spreads from his shoes to his legs, hands, and even his face.

"I looked like I'd been in a coal mine," he says.

It was 10 days after a fire tore through 4500ha of land, including 1000ha of conservation land. Knox had been forced to wait for the embers to die down before he was allowed to check on the jewelled gecko community he monitors for the Department of Conservation (DOC).

Before the fire, his typical gecko hit rate for six hours of searching was two geckos. Even for experts like Knox, who makes a living monitoring them, they're notoriously tricky to spot. Most of the time, they're nestled in hiding places amidst rocks, tucked into the tall tussocks, or hidden in branches of Coprosma shrubs, snoozing the day away.

Today, with the smell of charred tussock heavy in the air, his hit rate skyrockets. The gecko's usual hiding places are now ashes, but unlike Knox, the bright green geckos aren't coated in a layer of soot. In a black landscape they stand out, "like dogs' bollocks", he says. He sees 17 jewelled geckos alive, some dead McCann's skinks, a dead possum and one of our apex introduced predators, a stoat, which he watches "going into a little rock pile and coming out again".

Should the reptile survivors be shifted to another location with more shelter? The idea is thrown around he says, but, "where do you start and where do you finish?"

"To thoroughly remove geckos from 1000ha is probably going to take you all year. You would need an enormous amount of funding."

Instead, a ‘watch and wait’ approach is taken. Knox monitors the geckos in the hope their fate provides valuable knowledge about what happens after fire.

He returns again and again to the park and as the tussock slowly grows back, he finds fewer and fewer geckos. At first, this seems logical; the geckos have more hiding spots. But two years on he thinks differently. His most recent day of searching had a zero hit rate.

He's not sure whether it's because predators could spot them easily against a black landscape, a lack of sheltered nooks to escape snowy winters, a lack of food, or a combination of the three, but he thinks the geckos which survived the blaze perished in the aftermath.

Looking over the park now he sees patches of green vegetation. The tussock is back but the Coprosma shrubs which grow berries the geckos like to snack on aren't. "It could take 50 years for the habitat to be back to the way it was."

With hindsight, should the surviving geckos have been shifted after the fire? Yes, says Knox, but, "you've got to have someone that's prepared to fund the work".

His guess is 1000 to 2000 geckos died during and after the blaze. With an estimated total population across the country of about 100,000, it's a hit for the species, but not a fatal blow.

But it's a hit which could occur more frequently as the world warms. Researchers from the Crown research institute Scion estimate the number of fire-risk days in central Otago will triple by the 2040s. Other reptile experts worry this piles yet another threat onto species which exist in one small location. Sixty-eight reptile species across Aotearoa are thought to face a threat from climate change.

"The more this happens, the more the species will potentially become threatened," says Knox. "Some of these, these tussock areas, they're only going to get drier and drier probably. It'll be easier for fires to get out of control."

Loving nature to death

New Zealand has an abundance of endemic species found nowhere else in the world. Interwoven with our national identity, they've been immortalised in art and illustrations, graced currency, stamps, rugby jerseys, planes and souvenir tea towels. We've rested our Arcoroc coffee mugs on coasters depicting vistas wreathed in nature, and penned birthday reminders on calendars showing rocky forest streams with ribbons of water winding through them.

Research conducted on ‘New Zealandness’ by Practica in 2010 for advertising agency DraftFCB found our number one defining feature was our love of nature, which has a spiritual and soulful aspect to it. We see ourselves as inhabiting a lush, verdant country, with large tracts of parks, and flourishing flora, fauna and fungi.

But the statistics paint a different picture. Since human arrival, wildlife has suffered blow after blow. We’ve eaten away at their habitat, imported predators and weeds, failed to create laws to protect them, and now we’re turning the thermostat up on the world.

There’s a goal of zero human-induced extinctions from 2025 and beyond, but some experts are doubtful this will be met.

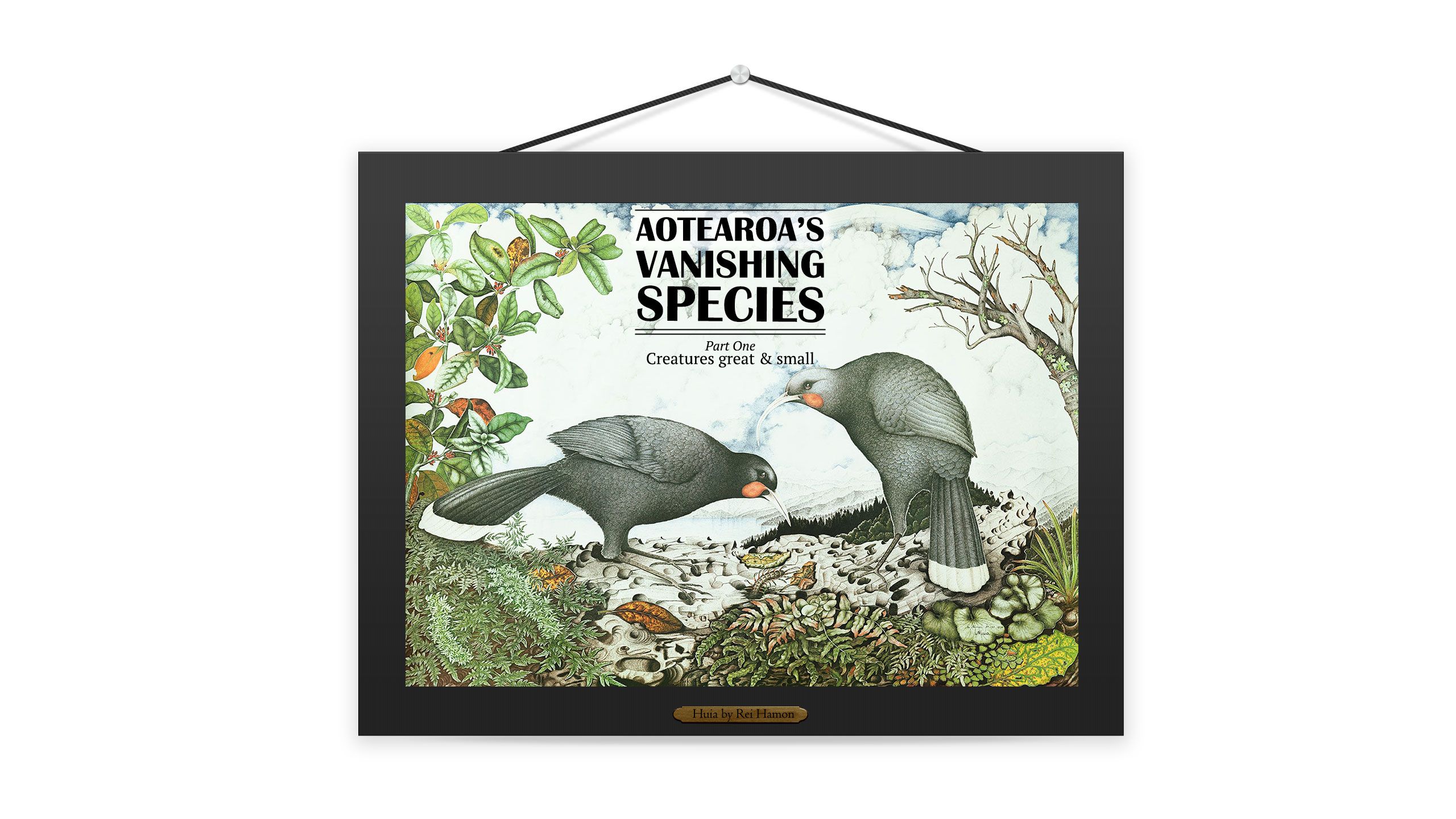

Without dedicated effort, other species unique to New Zealand may vanish from our wilds, only living on in the landscape paintings of Rei Hamon, or historical illustrations on coasters, tea towels and postcards for sale in souvenir shops. Others will be frozen in museum displays and scientific collections as memories of a New Zealand that once was.

New Zealand assesses the extinction risk of more than 8000 endemic species, these are species found nowhere else in the world.

Only 8 percent of assessed endemic bird species are classified as 'not threatened'.

Sixty-seven percent of assessed insect species are at risk of, or threatened with extinction.

Less than half of assessed endemic plant species are safe from extinction.

Sixty-nine percent of assessed lichen species are threatened with or at risk of extinction, or we know so little about them we don't know if they face extinction.

More endemic species are assessed as facing a threat of extinction, than are considered safe from extinction.

Counting our extinctions

"We are going to have more extinctions," says plant expert Professor Peter de Lange. He works at Unitec Institute of Technology, but previously was employed by DOC where he helped create the New Zealand Threat Classification System.

The name may sound dry, but it’s a system which helps us put a number on how many species are extinct, or are at risk of extinction, and gauge how close to the edge they’re teetering.

It’s our best view into the current state of our biodiversity, although knowledge gaps mean it’s a blurry view.

The system's four main categories are 'Threatened', 'At Risk', 'Data Deficient' and 'Not Threatened'.

While 'Threatened' may seem the worst, it’s the 2192 endemic species listed as data deficient species which weigh on his mind.

“The biggest threatened group we have in the country are our data deficient taxa,” says de Lange. These may be species where one example has been found and given a name, but little more is known.

“If there’s people out there looking, and they’re not finding it, it’s probably seriously threatened."

The system provides a rolling summary of threatened species, rather than a snapshot in time. Updating it for so many species is a task too enormous to do every year, instead groups of species are reviewed on a five-yearly cycle. Panels of experts trawl through all known research on species and log what’s known and what’s changed since the last update.

The risk of extinction is calculated based on the population size of a species, and the predicted trend of the population over three generations, or 100 years.

Getting assessed as extinct can take decades after the last official sighting of a species. The last confirmed sighting of the South Island kōkako was 55 years ago - it’s listed as data deficient.

It’s also important to note that not everything makes it into the threat classification system. Marine fishes have never been assessed. What makes it in is often based on whether there’s data available, and experts to help with assessments.

Perhaps the easiest way to interpret the data is to look at species which are classed as “not threatened”. These are species which, for now, are not likely to become extinct.

But they amount to less than a third of our endemic species.

Every statistic in the classification system tells a story and many of the species have an unofficial scientist mascot, who may feel like they're screaming into the void to make sure the species doesn't slide quietly into the extinct category.

The problem is if we think of saving species from extinction as a three-step plan, with step one identifying our most threatened species, and step three preventing extinction, step two doesn’t always have the research knowledge, resources or legal teeth needed to save a species. Even when assigned the most dire of status, there’s no automatic rule where money is assigned to protecting the species, or the species gets stronger legal protection.

The Russian doll effect and co-extinction events

A single species is much more than a line of data within the classification system.

Each one has a specific role in an ecosystem which goes unfilled when it vanishes. Like a Russian doll, the loss of one species can set off a cascade of extinctions.

This happened with our huia birds, driven to extinction in the early twentieth century. Only in recent years are we discovering the flow-on effects.

In 2008, from a tattered German museum display, a Polish scientist made a surprising discovery. Two long-dead huia birds, the female posed with its head slightly cocked in eternally quizzical stance, carried a secret they had kept for more than a century.

A feather mite's attachment to its host is so strong that it perishes when the bird dies, remaining as a dried mummy in a death embrace with the bird's feathers. The Polish scientist’s painstakingly careful scraping of the huia feathers collected mites from the dead birds' plumage.

Shorter than a millimetre long, and light enough to be blown into oblivion by a sneeze, the desiccated mite carcasses weren't from any known species.

When huia flew and hopped through our forests, the feather mites likely role was as a cleaner, dutifully emerging in the evenings when the birds were at rest, to scurry up and down the prized feathers and clean them of detritus.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, squeezed from their habitat, predated and hunted to extinction, it's thought the last huia vanished from the planet. For the tiny mite, the huia was its planet. By the time the mite species was given the name of Coraciacarus muellermotzfeldi in 2008, the scientific equivalent of being issued a birth certificate, it had likely been extinct for a century.

The huia was the entire world to another species; the louse Rallicola extinctus. As its name suggests, it too was discovered long after its extinction. The death of our last huia was what’s known in the science world as a co-extinction event, where the loss of one species cascades into the extinction of others.

And while the huia kept its mite secret for more than a century, there's a chance, like a Russian doll, the huia mite carried its own secrets. Mites can have many other species living in symbiosis within them, such as protozoa. If the huia mite were home to any species which favoured a single host species, these too would have vanished when the huia did. It’s possible the extinction of the huia took out more than just the huia mite and louse.

Extinction of the species within these groups considered at risk, threatened or 'data deficient', would leave us with this percentage of each remaining.

The hidden catch of doing good

Efforts are being made to turn the tide of extinctions and co-extinctions, and some of these, like Predator Free 2050, are grand. But even a well-intentioned grand effort can have unintended consequences.

Possums, weasels, stoats, ferrets and rats are in Predator 2050’s crosshairs, but not mice. This keeps University of Otago’s reptile and amphibian expert Dr Jo Monks awake at night, worrying that killing off the bigger predators could lead to an explosion of mice populations.

She warns not to discount mice's killing capability because of their size and suggests searching YouTube for a video of mice eating an albatross chick on Gough Island. “There’s a graphic image warning on it,” she cautions.

It’s a harrowing two minutes of compiled footage. A fluffy albatross chick, too young to fly, sits in its nest. As night falls a mouse, far smaller than the chick, appears, it wanders around the chick, moves to its rear and clambers part way up its back where it burrows into the chick's down, chewing through its skin.

Distressed, the chick reaches backwards with its beak to dislodge the mouse. It succeeds, but the mouse returns. Another mouse appears, then another and another, all clustering at the spot where the hole has been created.

The video ends in daylight with an adult albatross inspecting the chick, dead in its nest. Its rear end is a pink mess of exposed flesh.

Monks says reptiles have a unique problem when it comes to mice. Our temperate weather makes the cold-blooded creatures sluggish, but has little effect on mice.

The slow-moving reptiles can be an evening buffet for the mice, who return night-after-night slowly nibbling the reptile to death. “We have no predator control tools to sustainably suppress mice,” she says.

Only 3 percent of our reptile and amphibian species are considered safe from extinction. Another 3 percent have already vanished. Ten species teeter on the edge, classed as nationally critical.

Are we going to see more extinctions?

“I think we are,” she says.

Extinction of the species within these groups considered at risk, threatened or 'data deficient', would leave us with this percentage of each remaining.

Beetles, pine trees, dairy cows and the limits of the law

Endangered species are, unfortunately, oblivious to the modern human concepts of land ownership. As much as it would be useful for DOC, conservation work cannot happen only on publicly-owned land.

The task is much trickier on private land. Just ask the Eyrewell beetle, although you will be hard pressed to find one.

It's possible there were never many Eyrewell beetles to begin with. Only 10 have ever been found, all in the introduced pine trees of the Eyrewell forest, somehow surviving cycles of felling and replanting.

Now, dairy cows fill the land the trees once shaded. Ngāi Tahu Farming razed the forest in favour of 14,000 cows. Eckehard Brockerhoff, one of the scientists involved in catching the last beetles, says the conversion from forest to dairy farm was thorough.

“They had this mulcher, which was like rotating knives that were going over the top soil,” Brockerhoff says.

He thought at the time that if they wanted to get rid of the beetle or any other insects seeking refuge in the topsoil the mulcher, “will do exactly that”.

There were efforts to save the beetle but it fell through a gap in our laws. DOC has no power over private land. Forest & Bird tried to push for answers, but received none. At times, discussions were heated and one DOC employee was censured for sending an “emotive and preachy” email pleading something is done. Brockerhoff himself suggested that a pine reserve be kept in an area where most of the beetles have been found, but his request came to nothing. DOC and Forest & Bird staff were left to fret as the mulchers rumbled over places the beetle had been found.

A hunt for remaining beetles ceased in 2020, none were found after the conversion. Brockerhoff isn’t surprised. Even though some small reserves were created, these were only made after the blades had minced the topsoil and everything in it.

“I think there is a reasonable chance that it's extinct,” he says.

He’s often thought about writing an obituary for the beetle, highlighting how negative effects of the conversion were foreseeable yet “so little was done to protect it”.

Threatened species, even when classed as nationally critical like the Eyrewell beetle, aren’t automatically protected by law. The Wildlife Act can apply to species on private land if they're specified in the act - but there's a catch.

When the act was written in 1953, it focused on animals, and back then insects weren’t considered as animals. Some insects have since been added as honorary animals but the now possibly extinct Eyrewell beetle isn’t among them. If by chance any more beetles are found on private land, their fate depends on the landowner’s mercy.

Extinction of the species within these groups considered at risk, threatened or 'data deficient', would leave us with this percentage of each remaining.

There’s one extinct species which does have legal protection and it’s the only endemic freshwater fish species which is protected. The Freshwater Fisheries Regulations gives absolute protection to the grayling, a species last caught in 1923. The law forbidding catching it was added to the regulations in 1951, and survived a 1983 update of the act.

Other threatened species, like the Canterbury mudfish, have no legal protection in the regulations. There’s nothing stopping somebody catching and eating them on private land, other than the fact they’re probably not good eating.

Perhaps odder still, one of our ‘At Risk’ species falls into our fishery industry’s quota management system. Up to 137 tonnes of endemic long-finned eels can be caught each year. Eels only breed once in their lifetime before dying so every eel which makes it to a dinner plate or into a can of pet food, is an eel which has never had a chance to reproduce.

While threatened fish and insects struggle for protection, other threatened species have to first achieve recognition of their very existence. Trees, flowers - even fungi - are all in the fight for their lives against a biodiversity catastrophe.

Reporting, data and design by Farah Hancock.

Editor John Hartevelt.

Image credits:

Huia / Rei Hamon, supplied. Effects added by RNZ

Reptile and amphibian graphic - composite image containing the following:

Skink, gecko and frog images / Dylan van Winkel, supplied. Effects added by RNZ.

Insect graphic - composite image containing the following:

Moths and butterflies / Birgit E. Rhode, Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd, CC BY 4.0

Stoneflies / supplied by Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research

Wasps / supplied by Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research.

Eyrewell beetle / Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research, CC BY 4.0

Weevil / by Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd, CC BY 4.0

Velvet worm / Hoyholly15, CC BY-SA 4.0

Mite / CSIRO, CC BY 3.0

Katipo spider / Mark Tutty, CC BY-SA 4.0

Snail / Linas Jakucionis, CC BY 2.0.

Water species graphic - composite image containing the following:

Shellfish / Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand, public domain.

Grayling / Frank Edward Clarke, public domain.

Octopus / Darren Stevens - NIWA, Attribution.

Skate / W. J. Sparkes, public domain.

Flounder / Records of the Canterbury Museum, public domain.

Koura / Erebus (Ship).; Gray, John Edward; Richardson, John; Ross, James Clark; Terror (Ship), public domain.

Eel / Frank Edward Clarke, public domain.

Data source:

This work includes New Zealand Threat Classification System content which is licensed by the Department Of Conservation for reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.