Half a century of the Morning Report bird call

It started, as Morning Report items often do, late at night.

It was just before 11pm at night, in early 1973 NZBC all night programme presenter Robert Taylor wanted a sound to herald the start of the show and decided on the call of the Ruru/Morepork.

Ruru call recordings were somewhat difficult to come by in Wellington late at night, so Taylor went for the next best thing: he recorded colleague John Winchcombe doing a mostly accurate impression of the bird in the hallway.

It was all going swimmingly until he heard from NZ Wildlife Service staff member John Kendrick, who had a question about the very unique Ruru call playing each night.

"He said to me, 'what's that strange Morepork call you're broadcasting?'" Taylor says.

"I said 'well, what do you mean strange?' He said, 'well, it's a dialect I've never heard before' and I had to fess up and tell him that it was a fake that we had done because we couldn't get hold of the real thing.

"He said, 'I'm in the Wildlife Service in Bowen State building. Come up and see me, I'll sort you out'. I went over and I formed a lifelong friendship with John Kendrick, who was the sound recordist for all of our bird calls."

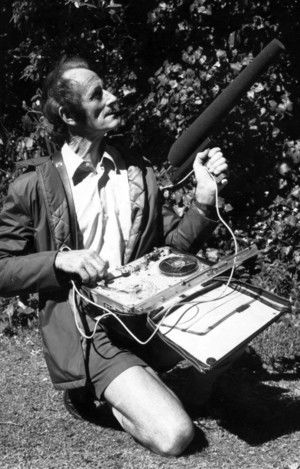

Kendrick, who died in 2013 at the age of 91, provided birdcalls to be played on air. He also gave Taylor the occasional opportunity to get his hands dirty.

"I went out with John several times on his recording trips to some pretty remote places, and you have to be pretty fit, very, very patient and very obsessed with what you're doing. John was totally that way.

"I never forget on Kapiti Island, we climbed to the top of a tree where there was a bird viewing platform and he says, 'come on, Robert, we'll go up here' and off he goes up the tree and I'm struggling along with a Uher tape recorder and two microphones panting and gasping. It took me about 10 minutes to get up there.

"That's the sort of people who have to do that job, you know, their enthusiasm is amazing."

John Kendrick in the field in the 1970s. Image courtesy of White Cloud Books / Upstart Press

John Kendrick in the field in the 1970s. Image courtesy of White Cloud Books / Upstart Press

Kendrick told Our Changing World in 2009 he spent his childhood developing a love of nature and early adulthood working for the army and then in radio sales.

In 1964, he joined the Wildlife Service, the predecessor to the Department of Conservation, as its audiovisual officer and created their sound library.

"It was the most wonderful job I could have dreamed of. It's what I've been doing for years, really as a hobby. But suddenly it became a vocation, it became my life's work."

Kendrick loved the job, which saw him headed all over New Zealand with his equipment to record bird calls, but it wasn't without challenges.

"Wind is a constant irritation and limitation because with wind, although we have of course microphone covers and some very effective windsocks, it's better to get a windless day because you get the incidental noise working through the foliage and you get that little rattle. Rain is obviously completely inescapable. You can't record when the rain is pouring down unless you've got a good assistant, which I didn't have."

The work was physically demanding, dragging around large pieces of equipment across uninviting environments, but allowed Kendrick to get close to wildlife most New Zealanders didn't get the chance to see.

In 1974, presenter Robert Taylor moved to mornings and started the tradition of the morning bird call. Morning Report began the next year and included the bird call from the start.

Geoff Robinson, who was a Morning Report presenter from 1976 until his retirement in 2014, aside from a brief break in the late 70s and early 80s, had plenty of experience with the bird call. One sticks out, he says.

"I've always liked the Kōkako. I found a word which described its call perfectly: 'plangent'. I think it was partly the word that attracted me, but then when I heard the bird call, I thought, yes, that that sums it up in a way that I couldn't explain it.”

Photo: Webb, Murray :Geoff Robinson, 2005

Photo: Webb, Murray :Geoff Robinson, 2005

Regular guests and staff quickly recognised the call. Robinson says one weekly guest used the call as his cue.

"On Tuesday morning, we would go to Jack Forsyth at the fruit and vegetable market for the best buys of the week and we trained him up so that he would keep talking as long as it is as needed and when he heard the bird, then he had to stop."

Listeners responded vociferously when it was suggested that the bird call be retired in 2005. Reports from the time note one angry listener hung a ‘Keep the Bird’ banner from her apartment window across the road from RNZ's Wellington office. The station received more than 1600 emails in support of the bird.

Robinson said the bird was worth keeping.

"The bird call was unique to National Radio, so why would you want to get rid of it?”

News of the bird's potential end even made its way to Australia, where Robert Taylor was living at the time.

"I used to get people here [in New Zealand], send me notes on what was happening news-wise. They said they're trying to do away with the bird calls, and I knew there was a big public outcry over it. The public want them there, they love them and I'm so glad."

The bird stayed, and in the late 2000s, when RNZ decided to expand the number of birds and the list grew beyond the original roster of around 30 bird calls played since the beginning.

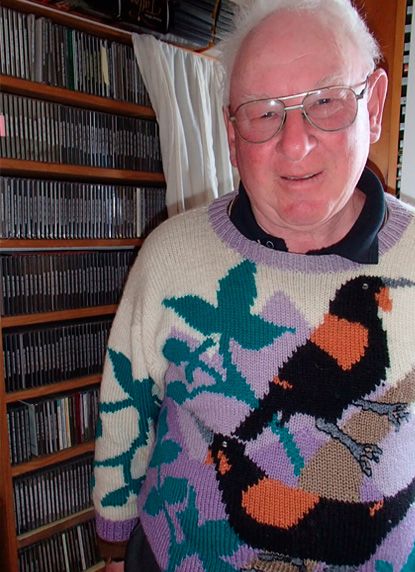

This time around, bird enthusiast and recorder Les McPherson provided the sound of the calls from his library. Like Kendrick, he had plenty of experience clambering over rough terrain with sound recording equipment.

"There are two shags, the Chatham Island [one] and one on Pitt Island. I had to go out there in the middle of winter, and it's not recommended... I didn't use the parabola on that job, but I had about 200 yards or metres it would be these days of cable."

Sound recordist Les McPherson in front of his sound archive which contains thousands of bird calls. RNZ / Alison Ballance

Sound recordist Les McPherson in front of his sound archive which contains thousands of bird calls. RNZ / Alison Ballance

McPherson's recordings have also been used in the NZ Birds Online database. Founder Colin Miskelly has long been a fan of the RNZ bird call and has made a game of trying to guess the bird before it gets announced. He reckons he’s right around 95 percent of the time.

"Usually if I get it wrong, it's because of the wrong species of crested Penguin or the wrong species of mollymawk because those groups of birds all sound very similar to each other."

Fifty years on from the beginning of the bird call Morning Report has hundreds of options available, with a different one played each day throughout the year. Each one has a custom tag, with the bird name often read in English and te reo Māori.

The voice announcing which bird is playing each day is different for each call, and while the voices are RNZ staff, none of them are presenters. Staff member Katrina Batten handled the recording, and said that's by design.

"I just asked backroom people producers, bulletin editors, reporters, [studio] operators. A lot of people said, 'can I record a bird tag? I really, really, really, really want to do that'. So, I would choose birds and mix them up and they would come and record 10 or 12 birds at a time."

Fifty years on from the beginning of the bird call Morning Report has hundreds of options available, with a different one played each day throughout the year. Each one has a custom tag, with the bird name often read in English and te reo Māori.

Bellbird / Korimako. Photo: Glen Fergus

Bellbird / Korimako. Photo: Glen Fergus

It's come at a time when New Zealanders have become much more aware of various bird names in Māori, says University of Otago professor Priscilla Wehi.

"There are birds which maybe 30-40 years ago we used to most often call yellowhead, for example and now much more often you hear them referred to as mohua.

"I think it is we as New Zealanders learn more about the birds and really start to appreciate them that our identity has also started to change, and we feel probably much more connected to the land here and to all of the species in our environments and so we're starting to actually ask ourselves what are these beautiful Māori names?

"And we really start to value those names a lot more because they tell us about the ecology or the behaviour of the bird, for example. So, there have been these real shifts and the names that we use."

Massey University professor Hēmi Whaanga says there’s often more than one Māori name for many birds, so the one referenced in the bird call in the morning could be different to what is used in other areas.

"The bellbird has 33 names that have been recorded for it. There's quite a lot of diversity and variation right across the country, and particularly for the little birds like the rifleman's got 26, the New Zealand Robin has 34 names and the Kākā has 30."

Potentially to the delight of many, the bird call is going strong with no end in sight in 2024. It's something Geoff Robinson is pleased about, a decade after his departure.

"I'm really glad the bird is still there. I think it's something so different that should be there and not questioned, just accepted. It's part of New Zealand, part of our history."

Geoff Robinson smiling during his last Morning Report Show. Photo: Diego Opatowski / RNZ

Geoff Robinson smiling during his last Morning Report Show. Photo: Diego Opatowski / RNZ