WHITE NOISE

Some Aucklanders have more say in their city's future than others

It’s our most culturally diverse city, but older, wealthier, Pākehā people have the loudest voice when it comes to shaping the city’s future.

Kate Newton reports.

All afternoon, the kids living next to Boggust Park, Favona, have been hooning up and down the bordering network of cul-de-sacs and no-exit streets: swapping scooters and skateboards, briefly disappearing into one house or another to find a basketball or siblings or friends, yelling and carrying on, cracking themselves up.

They’re 9, 10, 11 years old, there’s no school this Monday, and the sun’s out. A pair of journalists showing up in the street is just the latest momentary diversion in a day that’s been full of them. “Is this a story about the teachers’ strike?” one boy shouts.

This isn’t a story about the teachers’ strike. But it is a story about these rambunctious kids, and the Auckland they’ll grow up in.

There’s a community here in this pocket of Māngere, in south Auckland, as there are communities all over the city - people interested in each other and the place they live, with strong opinions about the issues that affect them. Whether those communities can speak up, though, or whether their voice is heard, seems to depend on where in the city they live.

Auckland Council recently adopted the Auckland Plan 2050: a lofty vision of what people living in New Zealand’s largest, most unwieldy city want the region to look like in 30 years – the values they think are important; their aspirations for the environment, transport, housing, and well-being.

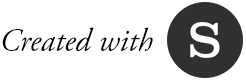

Except the 26,000 people who helped shape that plan and the council's long-term plan, who told the council whether it aligned with their own imaginings of Auckland’s future; those people, as a group, did not look much like Auckland. Only 310 of them were from the Māngere-Ōtāhuhu local board area, where Boggust Park is. For every submission from people living in that area, there were seven from people living in Rodney, four from Devonport-Takapuna and three from Hibiscus and Bays.

So who is shaping Auckland’s future? Who is its voice?

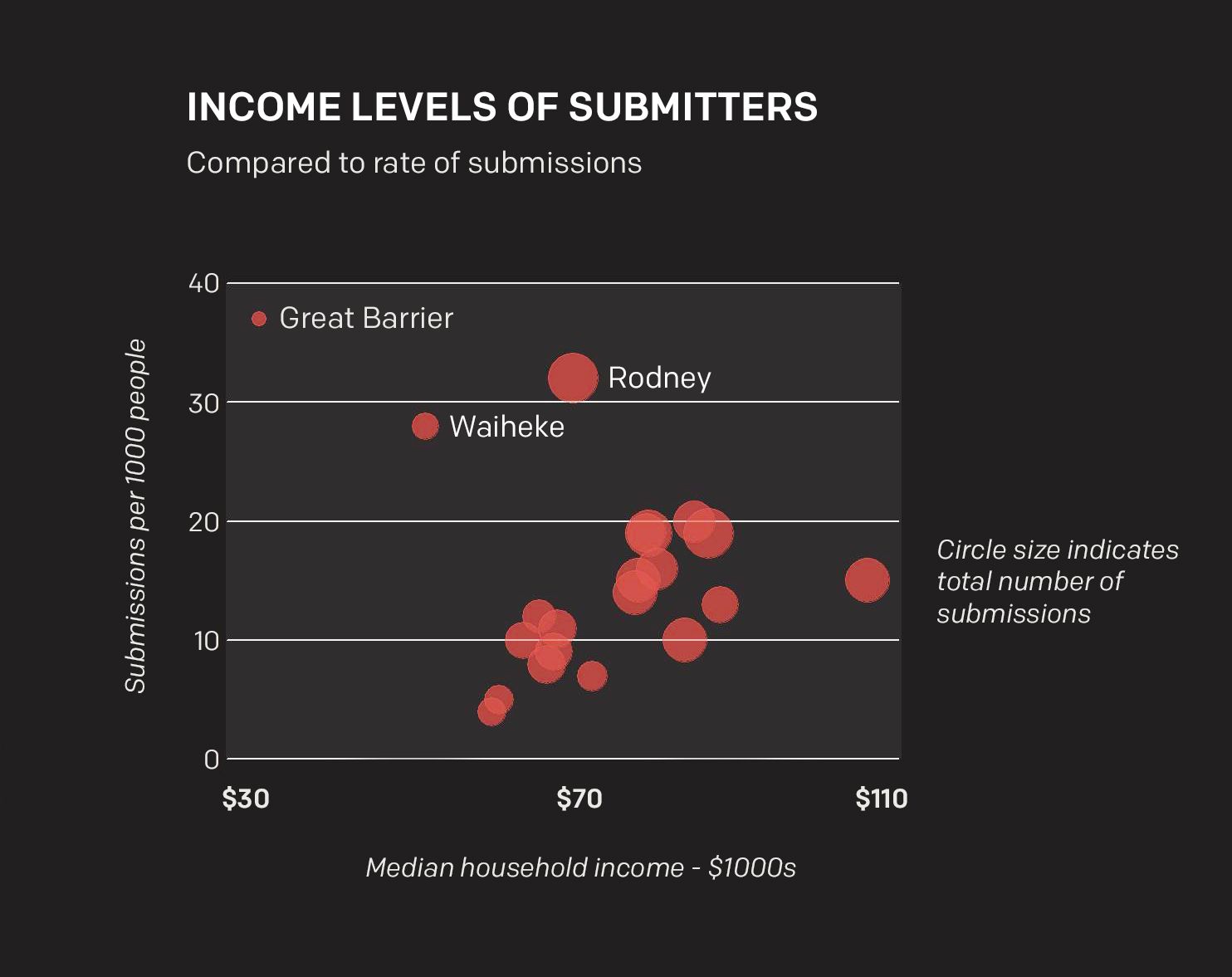

Auckland is ethnically diverse, it’s young, with a median age of 34, and it’s got huge income disparity. But when RNZ examined the submissions and feedback on the council's plans, three-quarters of the people who submitted were Pākehā or European (compared to just over half Auckland’s population). Two-thirds of them were from high-income areas. Seven out of 10 were aged 35 or older.

Researchers and democracy advocates say it’s a pattern that repeats itself across consultations. Despite the efforts of council to expand beyond traditional forms of feedback, in many instances it’s disproportionately Pākehā, older, wealthier citizens who are still dominating the conversation.

Round the corner from Boggust Park, the neighbourhood kids still audible in the distance, Deepa Raj has just got home from work. In places like Māngere, the conversation simply passes people by, she says. “We do have a lot of opportunities to raise our voices, to have a say, but most of our people do not know where to go.”

Māngere is the Pasifika epicentre of not just Auckland but New Zealand: at the 2013 Census, 39,000 people in the area, or 55 percent, identified as Pacific Islander - dwarfing the Pākehā population, which accounts for 18 percent.

However, of the already tiny number of plan submissions from the area, nearly half were from Pākehā residents, outnumbering the 41 percent that came from Pasifika. So not only is Māngere-Ōtāhuhu severely under-represented among the total submissions; the Pasifika majority there, which you might expect to be speaking with the loudest voice, is instead being drowned out.

Inside Māngere Town Centre, the bass beat from a daily public zumba class pumps from one end of the semi-enclosed shopping centre. It reverberates off square pillars painted with stylised palms and bounces down the flagstone concourse, past bright print dresses and Michael Jackson tribute t-shirts hanging in shop entrances; seeping into the office of the Māngere-Ōtāhuhu local board.

Lemauga Lydia Sosene is here nearly every day, her office’s glass frontage looking out onto the throng of people she represents. First elected to the local board in 2010 and its chair since 2013, she was born and schooled in south Auckland, and still lives in Favona. She has a strong face with hair pulled back in a tight bun and when she smiles, with lips closed, her eyes crinkle part-way shut.

She doesn’t flinch when she hears how few people from Māngere-Ōtāhuhu made a submission on the plans. She already knows. In a community where many people are migrants, where formal education levels are lower than average, where people are time and money-poor, convincing them to buy into a process that seems specifically designed to exclude them is “quite a mission”, she says.

“We have a lot of things stacked against us. The mechanism of filling out a two or three or four-page form - the language required - is difficult. It’s a face-to-face communication [that’s needed]. What is the question you’re asking me, do I understand it, and are you interpreting it [for me] in a way that I do understand it?”

Any perception that people simply don’t care is wrong, Sosene says. “Just because they haven’t put in an Auckland Plan 2050 formal submission does not mean that they are not engaged.” Yet she fears her community’s views are sometimes lacking in the Auckland Plan and, without strong advocacy from people like herself, will keep on being overlooked.

Māngere-Ōtāhuhu stands out in the data, but it’s no outlier. RNZ’s analysis shows Pākehā are over-represented in the submissions from nearly every single one of Auckland’s 21 local boards, which - to a certain extent - plan and make decisions for their area. In Waitemātā, for example, the central city’s ethnically diverse local board area, they made 85 percent of that area’s submissions. In Whau, where Pākehā are not even an ethnic majority, they made two-thirds of the submissions. And in areas where Pākehā are a large majority, their dominance of the feedback process is startling: 97 percent of submissions from Waiheke, 93 percent from Rodney, and 92 percent from Great Barrier Island and Franklin.

Across all of Auckland, Pasifika account for 15 percent of the population, but their share of submissions was just 7 percent. Māori and Asian ethnicities were also under-represented among the submissions, though less so.

What’s the risk of creating long-term goals and values, based on a feedback process heavily skewed against marginal groups?

“It’s massive,” public policy researcher Jess Berentson-Shaw says. “If you’re designing a city for older, Pākehā, well-off people, when we know that the city does not look like that now - and it is sure not going to look like that in the future - you’re planning and putting in place massive problems for yourself.”

The six aims of the Auckland Plan 2050 seem laudable. One of them is a ‘belonging and participation’ outcome, in which “all Aucklanders will be part of and contribute to society, access opportunities, and have the chance to develop to their full potential”.

But that won’t happen if the same people who are unable to speak up at the moment remain unheard on future decisions, Berentson-Shaw says. “There’s an impact on people’s sense of, ‘This is a process for me’, or, ‘This is a city that’s designed with me in mind’. People just lose any sense of autonomy or a sense of it’s worth making a contribution if you constantly feel like everything in your life is designed for someone who’s not you.”

The results of the Auckland Plan 2050 and long-term plan feedback process will likely mirror who’s having a say on other decisions, she says, because consultation traditionally excludes the same people over and over again. “If you are working multiple jobs - which we know is more likely for people on low incomes and Māori and Pacific people - if you have children to look after … then [it’s hard] actually just finding the time to even think about the issue, let alone turn up and submit and go through what often turns out to be quite a long process.” However, it’s “set up perfectly” for others to engage: people with the time, the energy and the awareness to both find out about consultations and then respond to them.

AUCKLAND'S OUTLIERS

“We’re predominantly European and middle-aged”

Start at the southern end of Muriwai beach on Auckland’s west coast, where gannets ride the prevailing sou’wester on their wing-tips and a salt-spray haze mutes the glittering black sand to the colour of tarmac. Get in a car and head inland until the bush gives way to tidy paddocks and reaches State Highway 16, which meets and diverges repeatedly with the sinuous twists of the Kaipara River.

Follow the rural highway all the way north to Wellsford and then head east, taking steep metal roads fringed with dust-covered foliage, and reach Pakiri - a beach as wide and empty as Muriwai but with white sand so fine it coats your skin like powder. The distance between the two beaches is 100 kilometres by road, 70 kilometres as the seagull flies, but you haven’t left the boundaries of the Rodney local board area for a moment.

Part of Rodney is quite keen to leave Auckland though. The entire local board area accounts for nearly half of Auckland’s landmass and a proposal to turn northern Rodney into its own territorial authority - denied in late 2017 - would’ve carved off a quarter of the super-city.

Local board chair Beth Houlbrooke believes that suspicion and, sometimes, outright hostility towards Auckland Council is partly what drives Rodney’s unusually high level of engagement. About 3.2 percent of Rodney residents - 1738 of them - responded to the Auckland Plan, which may not sound like much, but was more than double the overall rate. Only Great Barrier - an island community with a population of about 1000 and a strong self-sufficient streak - had a higher rate of submissions.

“Some would say that Rodney was dragged kicking and screaming into the super-city,” Houlbrooke says. “That created a high level of interest and perhaps cynicism and critique. People are vigilant that they’re getting good value out of the super-city arrangement because, on the whole, it was not a popular move.”

Residents’ interest in the council's plans isn’t a one-off either. “We have about a 45 percent [local body] voter turnout in Rodney and that’s well above the average [for Auckland],” Houlbrooke says.

Similar reasons are likely to be behind the high turnout among Waiheke Island residents, where the submission rate was also around three percent. The Hauraki Gulf island pushed unsuccessfully for self-governance at the same time Rodney was trying to break away, energised by what some residents saw as a lack of council action or interest in issues that were important to them. In its application to create a stand-alone Waiheke council, the group Our Waiheke emphasised the island’s “demonstrably enthusiastic, active” community, driven by its relative isolation and independence.

While Waiheke household incomes are below the Auckland average and Rodney incomes are only just above it, the two local board areas have some other important factors in common that were linked to higher engagement in RNZ’s analysis: 85 percent of their respective populations are Pākehā - the highest proportions in Auckland - and the median age in both areas is significantly older than Auckland overall.

And those are the people that local politicians, at least in Rodney, tend to hear from, Beth Houlbrooke says. “Because Rodney’s ethnic diversity is not as rich - we’re predominantly European and middle-aged … the kind of consultation that we’re used to doing up here is aimed mostly at those people.”

Helen MacKenzie steps backwards and looks up, shielding her eyes from the sun streaming into the pocket-sized garden at the back of her Devonport house. She and partner Lyndsay are political black sheep in this neighbourhood but they’re not hiding it: the brick chimney she’s trying to point out is painted red - and not just any red. To be sure it was the right shade, they called up Labour Party headquarters and asked for the colour code.

Unlike Māngere-Ōtāhuhu, her neighbourhood - comfortably wealthy, highly educated, predominantly Pākehā - was happy to have its say on the plans. Nearly 1100 people from Devonport-Takapuna local board area responded, at one of the highest rates of any area in Auckland.

MacKenzie, 71, has lived in Devonport for a quarter-century and has no trouble getting her views across if she needs to, she says - she knows which cafe her local board member haunts in the morning and she personally knows two Auckland councillors. “You do have to be educated and vocal and probably have a reasonable amount of money to have your voice heard,” she says. “There are parts of Auckland that are probably not heard very well at all - and some of those are the areas of Auckland that actually need a lot of attention from the council.”

Across the water in St Heliers, university administrator Kate, like MacKenzie, says she knows she can talk to members of her Ōrakei local board any time. Her community is “almost over-represented” at a local government level. “It’s quite a privileged, Pākehā-centric area and those people, like myself as a privileged Pākehā person, are pretty good at making sure their opinions are heard in public discourses.”

Not just heard - but taken seriously, Emily Beausoleil says. A democratic engagement researcher at Massey University, she says getting the chance to speak up is only the first hurdle. “Even being able to come to that table … the language that’s required to be able to be perceived as legitimate, as reasonable and persuasive, is really culturally specific.”

That means being succinct and direct. It means using formal language. It means being dispassionate and not becoming emotional, or overly expressive. It’s the kind of language that white, educated, middle-class people are really, really good at using, Beausoleil says. “Somebody who’s using cultural norms, values, languages that are most common and familiar can make their case really fast and sound really persuasive. So what can we do … to allow certain groups to have a parity or an equality?

In the final, dreary days of debate in early 2016 over Auckland’s Unitary Plan - which established planning rules for the entire region - one council meeting briefly distinguished itself. Dubbed “the worst Auckland Council meeting of all time”, it reached a chaotic apex when two members of the council’s youth advisory panel were jeered by older attendees while making a submission.

Leroy Beckett, the current spokesperson for Generation Zero, which advocates strongly for things like greater housing density and encourages younger people to submit to council, still remembers that meeting. “They had overflow rooms and people watching downstairs and you couldn’t get space to sit. It was really aggressive and you just felt it going downhill.”

The memory agitates Beckett. He’s buttoned up in a suit jacket and shirt but words tumble out of him. That meeting was “the clearest symbolism” of how Auckland’s marginal voices get drowned out. “It completely represented what we’d been seeing in other council meetings, in local board meetings, at consultations, for the entire time I’ve been doing this,” he says.

The skewed feedback on the plans shows not much has changed in the interim, he says. Auckland’s median age is 35, but 70 percent of the submissions were made by people older than that, even in areas with younger populations, like Waitemātā and Maungakiekie-Tāmaki local board areas. “Auckland’s facing multiple crises … that we need big change on and big ideas on,” Beckett says. “That change is held back by the current consultation process, it’s held back by the people who are being listened to in council.”

Leroy Beckett says the Auckland Plan submissions mirror what he sees in many consultations

Leroy Beckett says the Auckland Plan submissions mirror what he sees in many consultations

He actually likes the “fairly ambitious” 2050 Plan. But he worries about how it might play out in reality and whether its aims will be derailed by the same loud voices. “We want to be a more sustainable city, a more compact city, a more equal city ... but once it comes down to consultation level and we get to implementation, all of those values fall away.”

There might be some answers overseas. “There’s work they’ve done in Toronto … where they have a panel that’s demographically representative they use to make their decisions - people get called up, basically like jury duty,” Beckett says. “But it’s still important to talk to the community, to actually go out and talk to the people who will be affected.”

Auckland Council has already shown it’s capable of more participatory, inclusive forms of consultation, Jess Berentson-Shaw says. The Southern Initiative - a council-funded programme to solve some of south Auckland’s most ingrained problems - ran a project in 2017 to find out about the day-to-day reality of parenting in the area and what would make a difference for those families. They wanted to hear from mothers, many of whom had young children, struggled for money day-to-day, or were solo parents: all factors that would normally prohibit any kind of participation, let alone a three-day workshop.

So the programme removed as many hurdles as it could, Berentson-Shaw says. “The Southern Initiative provided childcare, they provided a means for people to access food, and they helped with transport. So they recognised that some of the impediments to engaging are just really practical.” In the end, 30 women and their families took part - a much smaller number than some other consultations, but with far greater depth.

Yes, there’s an upfront cost to getting that kind of feedback, Berentson-Shaw says. “But when [traditional] consultation goes wrong and takes a long period of time and doesn’t get the policy changes that are really needed … we’re going to have some really long-term impacts that we’re going to have to deal with.”

Jess Berentson-Shaw says the council needs to completely re-think the way it engages with Aucklanders

Jess Berentson-Shaw says the council needs to completely re-think the way it engages with Aucklanders

The Māngere-Ōtāhuhu local board has already been pushing council officers to make the feedback process friendlier and less opaque, Lemauga Lydia Sosene says. Stop asking people to grapple with multi-page forms, or attend a meeting at an inconvenient time. “We ask officers to have a BBQ of some sort - something more than just a cup of tea and a biscuit - so that we can call our people to say come along, and then you can have an engaged conversation. And rather than gather your thoughts on an actual form where you’ve got 20 questions, actually a couple of post-it notes - which are quicker to record your thoughts on.”

The next hurdle is to convince both council staff and councillors to treat that information - along with other non-traditional forms of feedback like Facebook comments - as seriously as they would any other type of submission, she says. “We’ve got to find ways of making it easier… I get constant complaints that Auckland Council processes are not easy to get involved in.”

They’re complaints Kenneth Aiolupotea is well-acquainted with. As engagement manager for Auckland Council, he estimates he and his staff have overseen about 100 consultations in the last year - from the 2050 Plan to the design of playgrounds. He acknowledges the demographic skew but says that doesn’t hold true for all consultations, particularly very local issues.

Surely the 2050 Plan and long-term plan numbers concern him, though? Think of the consultation on the 2050 Plan, in particular, as “a snapshot in time”, he says. “That was the first part of the conversation and our challenge now is to say, well, given that was the exploratory phase … we are clear about the broader context of where we want to take Auckland, how do we make sure that Aucklanders, particularly those groups that weren’t as involved in that first step, are more involved going forward.”

Engagement staff already hold Pacific fono in some areas and are trying to use council-run events to gather informal feedback on other plans and projects. The People’s Panel - a self-selecting group of citizens who get sent monthly online surveys - has up to 30,000 to 35,000 people involved at any point in time. It’s a quick and efficient way of gauging public reaction, but it’s self-selecting and has some demographic flaws. “We are aware where there are peaks and troughs and we have a recruitment strategy in place.”

Kenneth Aiolupotea says the council is broadening the way it gathers feedback

Kenneth Aiolupotea says the council is broadening the way it gathers feedback

The council is trying out various social media and digital tools, Aiolupotea says. An interactive website set up by Panuku, the council’s development agency, is currently soliciting feedback on plans to redevelop the centre of Panmure. Users can drag icons onto a map of the area to say what they like already, suggest changes or ideas, or highlight safety issues. Whether it’s attracting people who otherwise wouldn’t get involved is difficult to tell just by looking at the site, although users are asked to provide demographic information.

UpSouth, another online tool, targets south Auckland communities, asking questions that people can respond to in any form they choose, and paying a nominal amount of money in exchange.

However, the type of participatory democracy used in the Southern Initiative’s project isn’t always feasible, he says. “Council obviously thinks that’s really, really important for us to do, but the practicalities though - in terms of our ability to provide that opportunity all the time, in every instance - that makes it quite challenging.”

It’s a battle to even make some communities aware they can help shape the city around them. “When I joined council I had no idea as to the extent to which it actually impacts on my life and I think that would be the same for a lot of Pacific people,” he says. “Finding the way to engage with them in a way that they can see the relevance of council is really, really important.”

What if that doesn’t happen? “It means our ability to make good decisions is limited. And our ability to build a city that we’re going to be proud of is also quite limited.” So are any of the new forms of feedback making a difference? He can’t answer off the top of his head. “I would certainly hope so.”

The council does appear to be trying hard to reach a wider audience, Jess Berentson-Shaw says. But even some of the new tools the council is using may not reach the most marginalised Aucklanders. “The process of online consultation immediately cuts out a lot of people who don’t necessarily have access to the internet.”

Language is still a barrier: the Panmure website explains its purpose in several languages, but the interactive icons are only available in English, and so far all of the comments left have been written in English too. Likewise, UpSouth seems geared towards English speakers too.

The change that’s needed is more radical than just using different tools anyway, Berentson-Shaw says - it’s changing the consultation itself. She doesn’t buy the argument that participatory forms of decision-making are too costly or time-consuming to use all the time. “It’s the difference between upfront cost and long-term value.” And Auckland Council could start now. “Why not be bold? Why not say we’ve seen the data, we’re not okay … that the same people get included so we’re going to make a bold statement and try a new way.”

TINO

“In the past, we haven’t been heard at all"

Tino Malo fans his face with his hands. He’s just got home, it’s hitting mid-20s even though the sun has passed its afternoon peak, and he’s woozy from an unseasonal lurgy.

He wants to talk about Avondale though. He’s 24 and estimates he’s lived in the central west suburb for 21 of those years. He loves it - how close it is to town, the cheap bakeries and the Chinese takeaways on the main street, and the sense of community he’s always felt here.

Last year, Malo was one of the #PeopleofAvondale - a series of posters that mushroomed along a fence on Great North Road, the brainchild of the I Love Avondale community group and Facebook page. That page started life as a social media project in 2014 but has since blossomed into a rallying point for residents proud of their suburb, but sick of the neglect it has suffered. “In the past, we haven’t been heard at all - we’ve been pushed aside,” Malo says.

So they went looking for their own way to speak up. “We had a workshop not long ago, about three, four months ago, and it just brought anyone in Avondale ... who wanted to help, or have a say in the community - they were invited to this community workshop, which was awesome.” The workshop was organised by the community but supported by the council, which is planning a regeneration programme for the suburb and happily coat-tailed on the wave of homegrown engagement.

In some ways, Avondale represents one version of Auckland’s future. Its population is similar to what statisticians estimate Auckland will look like in 20 years: more people from Pasifika and Asian backgrounds, fewer Pākehā. Without the resources to fight development the way wealthier suburbs have, it’s been targeted for more medium-density housing. Already, apartments are popping up along the edge of Avondale racecourse.

Malo has no idea if Avondale gets its fair share of the conversation in Auckland, but at the moment it feels like his voice matters. “Compared to what it was like in the past, we’re definitely being heard.”

Strike day is nearly over and the Māngere Bridge waterfront is dotted with people soaking in the last of the sun before it sinks below the Manukau harbour entrance.

A boy, maybe 6 years old, takes a photo of his parents while the dry tips of grass glow golden around them. Another family searches the rocks next to a boat ramp for shellfish; children pound up and down the jetty, swooped up by parents and big siblings for piggybacks. A couple huddles close on a bench on a short finger of land jutting out from the reserve, while behind them the olive-green tendrils of mangroves snake far out into the mudflats.

For Lemauga Lydia Sosene, Auckland’s twin harbours are symbols. There’s a “huge focus” on the Waitemātā harbour, she says: should we extend the wharves for the America’s Cup or for cruise ships? Expand the port? Should we build a waterfront stadium? How will that affect the boaties and sailors; the fragile, tidal harbour beaches?

But no one is really talking about the Manukau harbour. “The Manukau harbour is very dirty - it’s uncared for; it’s unloved.” Even up that conversation, she says, and it might be a sign you’re getting somewhere.

You can view the full data analysis used in this story here.

This story was updated on 25 January, 2018 to include references to Auckland Council's long-term plan, which was consulted on alongside the Auckland Plan 2050.

Reporting, Data Analysis & Visualisation Kate Newton

Executive Editor Veronica Schmidt

Visuals Dan Cook

Graphic Design Scott Austin

Art Direction Dave Wright