INVESTIGATION

The suicides, sackings and stressed staff of Tauranga Hospital

A nurse leaves a suicide note addressed to his colleagues. Another kills himself after feeling mistreated at work. A third's suspected suicide is under investigation. What's going on at Tauranga Hospital?

Warning: this article contains discussion of suicide and other content that may be distressing.

It was 7 July, 2005 and Jeremy Avis was on his way to Great Ormond Street Hospital in London where he was employed as a registered nurse.

“He was early that morning for work and he thought, ‘I won’t get on the bus, I’ll walk’,” says his mother, Mary Avis.

At 9.47am the double-decker bus Avis usually rode was blown to pieces by an 18-year-old suicide bomber. Thirteen people were killed. His colleague lost her leg in the explosion.

“He missed death that day,” says Mary. “I often think about that.”

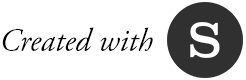

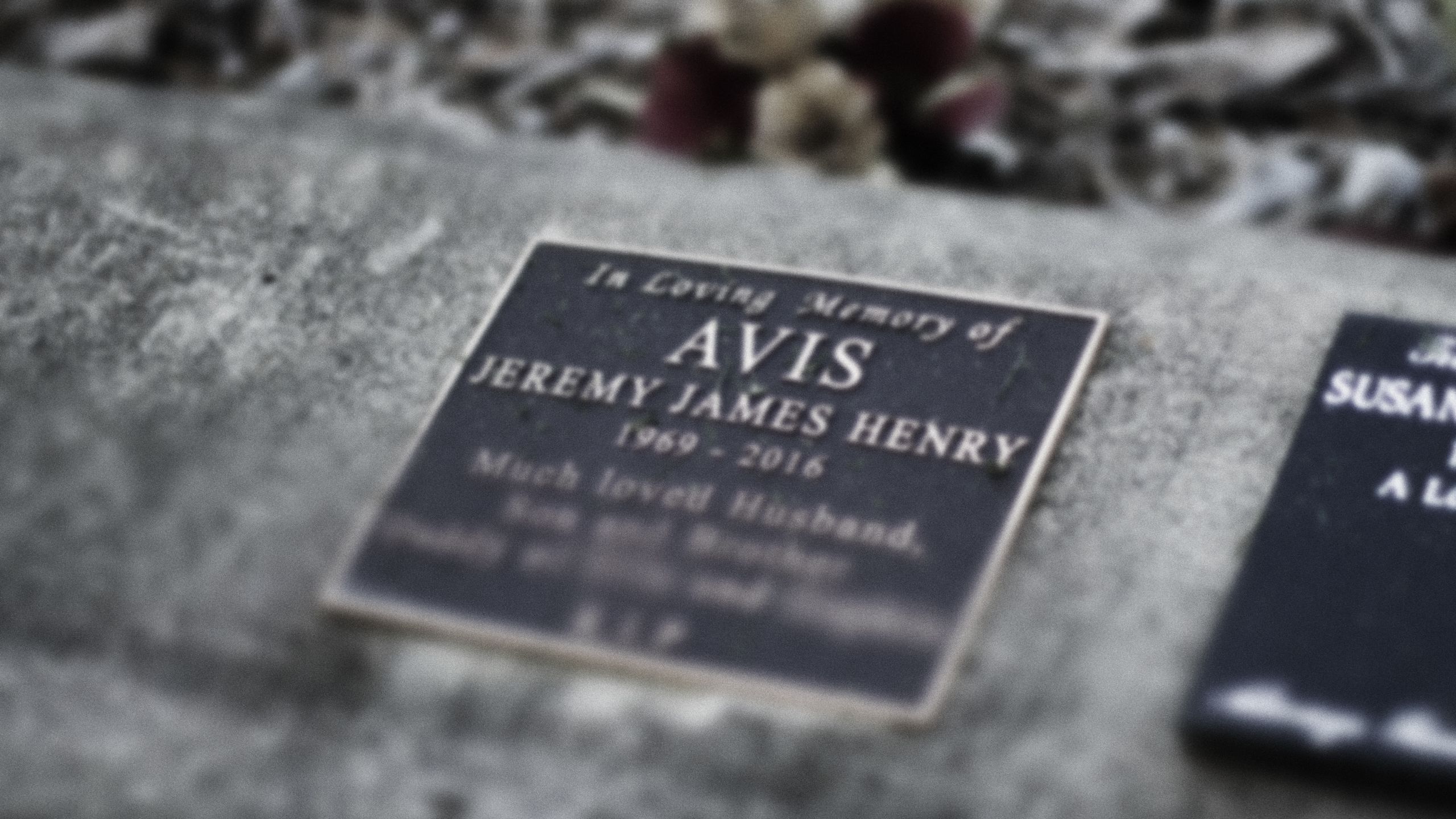

Mary and her husband, Jim, think about their son every day. Photos of him and his two young daughters are dotted around their home in Omokoroa, just north of Tauranga.

Avis spent years working in hospitals in the UK and travelling Europe helping perform heart valve replacements. Eventually he decided to move home, closer to his aging parents.

In 2013, Avis landed a job at Tauranga Hospital. By the time he left in early 2016, he was a shell of his former self, his family say.

In his first year, Avis was hit across the face by a coworker. When he complained, his family say the Bay of Plenty District Health Board (DHB), which runs the hospital, told him the coworker had a medical problem and nothing else was done.

In 2015, Avis felt punished after foregoing normal protocol to save a man’s life. He was put on supervision for six months, during which, his family say, he felt belittled and bullied by management. In an email to a former colleague before he died, Avis said he was avoiding his manager “like the plague”.

“I could see he was losing confidence in himself,” says Mary. “He became distant,” adds Jim.

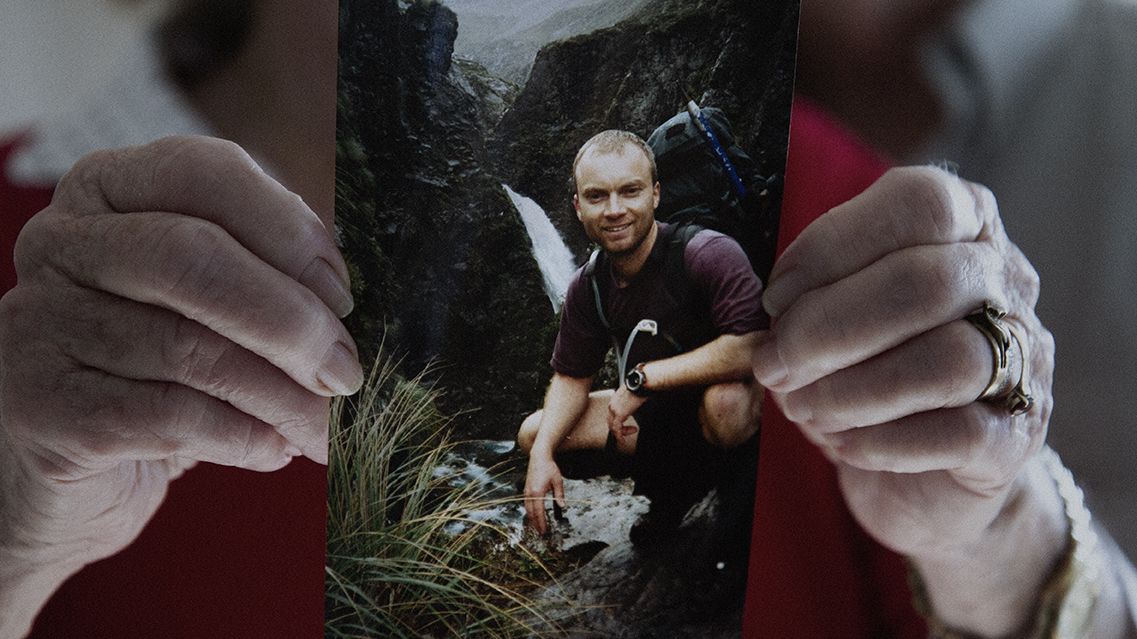

On 26 July 2016, nearly 11 years to the day of the London bombing, Avis committed suicide.

“It’s bullying that erodes people's confidence. It just does. It kills them, it destroys them,” says Mary.

“They didn’t treat him as a human being, I felt, with any dignity. I felt he was trod on.”

The Wireless has spoken with more than a dozen former and current staff at the Bay of Plenty DHB and uncovered a pattern of staff feeling bullied, questionable management decisions, and suicides.

Since 2013, at least two nurses, including Avis, who felt mistreated at Tauranga Hospital have killed themselves. A third nurse's suspected suicide is being investigated by the Coroner.

Bay of Plenty DHB staff have told The Wireless their bullying complaints were ignored and, in the worst cases, victims lost their jobs after speaking out. They say disciplinary processes were used by management to belittle and humiliate employees and nothing was done about multiple physical assaults. Staff also say their unions are largely powerless and the government agency put in place to enforce the law won’t investigate their claims.

A nurse who killed himself in 2013 left behind a note to his colleagues on the ward where he worked at Tauranga Hospital: "I hope you are all happy now that I’m gone. I look forward to meeting you all again in Hell!”

A suspected suicide of another Tauranga Hospital nurse in 2017 is still under investigation by the Coroner. Multiple sources say she felt poorly treated by management.

The Bay of Plenty DHB chief executive Helen Mason said the suicides were devastating. "These have been distressing events for all involved; for the families and also for friends and work colleagues."

But she says the DHB has found "significant and material differences" between the accounts given to The Wireless by staff who felt mistreated and what appears in the DHB's records, which she says, she "firmly stands behind".

Read the DHB's full statement here

The Bay of Plenty DHB wouldn't provide the number of bullying complaints made by staff over the past six years. “We did not track the information prior to April 2017,” it said.

Since information has been tracked, between April 2017 and March 2018, the DHB recorded 13 formal bullying complaints: three were unsubstantiated; three were substantiated; seven are still under investigation.

The DHB has previously denied allegations that it condones bullying. Mason says the DHB “is firmly committed to an anti-bullying culture and take any allegations of inappropriate behaviour very seriously”.

But Jeremy Avis’ family disagree. He felt bullied, belittled and had nowhere to go for support, they say.

“They didn’t treat him as a human being, I felt, with any dignity. I felt he was trod on,” says Mary. “I want them to see how many lives have been affected because of what happened to Jeremy.”

Ana Shaw, a straight-talking South African, is a tough lady but she felt bullied at Tauranga Hospital and it left her crushed. She takes out her phone and plays a video of her grandson blowing her a kiss. It’s her family that keeps her going. Without them she might be dead.

“[I was] crumbling, going home crying, thinking can I just overdose on something? Where’s the highest bridge to jump off? How do I leave my son in a foreign country without a mother?”

Shaw has 24 years' clinical experience. She trained in South Africa and immigrated to New Zealand on the skills shortage list.

In August 2010, Shaw started work at Tauranga Hospital. Four years later, she was fired.

The problems started shortly after she arrived at the hospital. She remembers when an inspiring quote was posted on the staff room wall: “Everybody needs encouragement; you can speak a word that changes someone’s life!”

“Some of the staff had a field day adding words to it,” says Shaw. “I saw it and ignored it. One of the girls who didn’t like me asked me if I’d seen it, then sniggered and walked off.”

Words like ‘lesbian’ and ‘average’ were scrawled over the poster. Someone had circled ‘needs encouragement’ and wrote ‘fired’ in a highlighter, Shaw says.

She tried not to let it bother her but she was hurt. “I went home to my friends and poured my heart out. I couldn't believe it,” she says.

Shaw took the poster to management suspecting they’d have a word to staff, but nothing was done, she says. “Bullying is worldwide, you can’t blame New Zealand for this. But I’d never dealt with it in this degree of maliciousness.”

Shaw continued to feel bullied. It was ongoing, sometimes subtle, and slowly eroded her confidence. She says a colleague called her a “black lady”, another said she was an "African wildebeest", and a third told her to go back to South Africa. Once, a colleague complained in front of management that she “walked too fast, spoke too fast, and worked too fast”.

One staff member repeatedly tampered with her patient notes and management blocked her learning opportunities, says Shaw. She felt belittled, demeaned and ignored. Once, she says, the aggression was so obvious that a patient stood up for her.

“No matter how many times I raised bullying issues, no matter what I raised, nothing was ever actioned,” says Shaw.

She raised her complaints with her union. Emails from her union, Apex, show they suggested she keep detailed records of incidents. Shaw says she didn’t receive the support she hoped for.

At one stage, Shaw emailed the DHB and asked for mediation with a coworker she felt treated her badly. The email response from HR says it “doesn’t get involved in interpersonal conflict”. In 2013, HR also told Shaw not to copy them into emails after she raised a concern that “relevant professional information” was being kept from her by a manager.

“My mental health declined drastically,” says Shaw.

She recalls how in 2011 the DHB paid a contractor to run an anti-bullying programme called 'Taking The Bully By The Horns' after its annual report identified bullying as a concern. The DHB said the programme was “favourably received”. Shaw calls it a “waste of time”.

The DHB is currently running another programme, called “Creating our Culture”, aimed, in part, at dealing with what CEO Helen Mason calls “inappropriate behaviour”.

“We have received a lot of very positive feedback about the programme, from staff, our employee union partners, and our patients, and are proud of what it has achieved to date,” she says.

Shaw remembers when her situation at work took a turn for the worse. In 2014, there had been a mix up with a reporting process that involved vital patient information. After one patient wasn’t called back despite having serious health problems, Shaw felt it was important to raise the issue with the team.

She sent an email to a manager and six colleagues. In it, she described the problem and asked everyone to “work together and not against each other” for the well-being of patients.

“I’m very straightforward and I have learnt that the culture here is very different.” But other than being to the point, Shaw doesn't see anything wrong with the email.

Nine minutes after she pushed send, the manager responded and included her colleagues. “Do not address my staff in this manner,” she wrote.

It was a public dressing down. Shaw felt frustrated but, by now, she was used to feeling this. Except this time was different; the manager launched a formal investigation into Shaw’s email.

“I was devastated. I had been complaining about multiple incidents of bullying and harassment over several years and nothing had been done. Then I sent out an email and they carried out a full-blown investigation.”

After a four-month investigation, the manager produced a 50-page report in which she concluded that Shaw’s 11-line email breached DHB policy and recommended she be disciplined.

“I felt they were trying to put a mark against my name, basically to shut me up. I thought, how could they discipline me on my email and yet ignore all my grievances?”

Shaw had had enough. She hired an employment advocate who lodged a personal grievance on her behalf with the DHB in late 2014.

Shaw was put on “special leave” and asked to produce evidence of the bullying. She spent weeks compiling documents, in the hospital library, which she felt proved she was being mistreated: the poster with hurtful words; emails from management to show her career development was being obstructed; messages from HR.

She handed in 150 pages to the DHB. Five days later, she was told she was being investigated for “breaching patient confidentiality”.

Shaw had included photocopies of patient reports in her evidence because she felt the tampering with her notes was evidence of mistreatment. She insists the patient records never left the hospital grounds. She says they never went to anyone else other than the DHB. She redacted the names with black marker but some patient details became visible when she photocopied them.

“I was shocked that I could be in trouble for providing information confidentially when I was asked by the DHB to do so,” she says.

Her employment advocate argued her case, telling the DHB it was their understanding that the information provided had not breached patient confidentiality as it had only gone to another employee within the organisation. But, in March 2015, she was fired.

“This is mental torture. I had never had any warnings or disciplinary marks against my professional conduct in 32 years. What have I done to deserve this?”

Shaw was left without a job and desperately needed an income to support herself and her son. She applied for more than 50 positions. She tried for a job at a supermarket but was turned down because of her dismissal from the DHB, she says.

Five months after she was fired, she got a job as a retail assistant. The drop in income meant she had to move out of her rental and in with friends. Her mental health began to slide and she was diagnosed with depression, which she had never experienced before. She’s been on and off medication since 2016.

Shaw decided to take a bullying case to the Employment Relations Authority (ERA) but her evidence was deemed inadmissible as the ERA weren’t satisfied that she raised the issues with her employer within a 90-day period. She’s still waiting to have a separate case – unfair dismissal – heard by the ERA.

The DHB says it won't comment on Shaw's case while it is before the ERA, but it did say it "believes these historic incidents were investigated and appropriate actions taken at the time".

“I know of deaths at the DHB. If we don’t speak up for them, then who will?” says Shaw.

“I won't drop the case because I have to clear my name, it’s for integrity and for people to be accountable.”

“The bullying was continuous … the stress got so bad that I went into early labour twice.”

Where can staff turn to when they feel they’re being bullied? Unions are often a first port of call.

The New Zealand Nurses Organisation (NZNO) has over 46,000 paying members. When asked how many bullying complaints had been brought to them in the last three years, they told The Wireless they did not keep count.

“Unfortunately we do not have the level of detailed data that you are requesting,” says Hilary Graham-Smith, associate professional services manager at NZNO.

The staff The Wireless spoke to describe their unions as “lacking power”. One former nurse from the Bay of Plenty DHB refers to the unions as “broken reeds more suited to agreeing with the employer than defending the individual”.

A nurse from Tauranga who worked in the private sector says the union didn’t adequately support her when she was struggling with her manager.

“The bullying was continuous. I ignored [the manager] a lot but when I was pregnant with my youngest, the stress got so bad that I went into early labour twice.

“You think when you pay all this money to the union they will just come in and get it sorted with the manager. Totally not the case at all. I phoned them a lot but they never come into the hospital. I got told it would make it worse for me,” she says.

Some staff said they are afraid of approaching the union because they fear they'll be seen as troublemakers by their employers.

Before he died, Jeremy Avis emailed a friend saying he didn’t want to go to the nurses union. “I really need a job,” he wrote. He noted how another colleague who felt bullied by management, like him, was “wary about approaching them”.

However, he eventually joined NZNO and paid membership fees until a month after his death. His sister, Kim Audas, approached NZNO after Avis’ suicide and requested help with her brother's case. She wanted answers from the DHB, but the union told her they couldn’t help.

When The Wireless approached NZNO for comment, they said they couldn't discuss the case for privacy reasons.

The Bay of Plenty NZNO union organiser, Angelia Neil, says bullying is not as widespread as people think.

“I’ve represented hardly anyone for a pure bullying case,” she says. “Really, there have been a couple of isolated cases where there was inappropriate leadership and the DHB addressed that quickly.”

“Often it's hard because it’s mixed up in performance issues. It’s not as cut and dry as someone going into the office and being bullied.”

Neil says the DHB have been working hard to improve culture at their hospitals and have been supportive of the union and their representatives.

“It sounds like I’m defending the DHB but I’ve found that they’ve bent over backwards, they’re very polite to people, and I’ve never seen anyone treated unfairly by the DHB.

“In all the time that I've been covering it, I haven't found this DHB very punitive. I’ve actually found it to be very people-focused.”

When asked about nurse suicides, Neil says she was aware of two cases and that “there was no bullying in either”.

“It’s hard when you’re dealing with someone who is really depressed. Sometimes they’re lacking insight and that can make them hard to deal with.”

The Nursing Council wouldn’t comment on whether it was aware of bullying within the health sector or whether it considered it a prominent issue amongst nurses. Nursing Council chief executive Carolyn Reed says the organisation should be notified if nurses’ behaviour “impacts public safety”.

One nurse told The Wireless she approached the Council about being bullied by the DHB but was told that because patients weren’t harmed, they couldn’t do anything.

“If we are not protected by WorkSafe, what do we do next?”

If staff decide to take their grievances further, they can go through the Employment Relations Authority; a civil process that deals with employment disputes like payment of wages or unfair dismissals.

Data from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment shows that 196 applications have been made to the ERA against DHBs around New Zealand since 2012. Fifteen of those cases involved the Bay of Plenty DHB.

According to an employment lawyer, each case taken through the ERA can cost a DHB between $20,000 and $100,000 in taxpayer funds.

The Bay of Plenty DHB says only two of their 15 cases were related to bullying and they spent about $65,000 defending them.

In 2009, a Bay of Plenty DHB employee won over $60,000 in a personal grievance case at the ERA after her managers unfairly capped her sick leave when she suffered from “work-related stress”.

A psychologist working for the same DHB was awarded three months' salary and $7000 for hurt and humiliation after his managers did not properly investigate a bullying complaint he made, and did not keep him safe while the investigation took place, according to a 2013 ERA ruling.

In 2014, a Bay of Plenty DHB nurse won about $2500 in an unfair dismissal case at the ERA. The DHB fired her for “undermining authority” after she had raised concerns about feeling harassed by her manager. Documents show that during one interaction, a witness saw the manager raise his voice at the nurse and say, “you know we could dock your pay?” He paused before adding, “but we won’t.” The ruling outlined that the information used by the DHB to prove the nurse had undermined authority was “equivocal, wrong or does not exist”.

When asked how much money the DHB has paid outside of court to settle disputes, it told The Wireless “we do not track this information”.

The Wireless is aware of at least two settlements, which saw the DHB pay out a total of more than $80,000.

The ERA is primarily designed to deal with employment disputes, like pay and leave issues. It can penalise employers for “repeated verbal or emotional attacks” on an employee but complaints must have been raised with the employer within 90 days of it happening. With the sometimes ongoing and subtle nature of bullying, this can be difficult.

Bullying is considered a psychosocial health risk in a workplace and, under the Health and Safety at Work Act, employers have a legal obligation to deal with it or they could face prosecution.

WorkSafe is the government body tasked with regulating the Act but, despite receiving at least 100 complaints about workplace bullying, WorkSafe has never prosecuted anyone in a bullying case.

The general manager of strategy and performance at WorkSafe, Jude Urlich, says the organisation investigates the most serious allegations of workplace bullying, focusing on cases where the person has been diagnosed by a specialist as having a serious mental health condition and where there is a clear link between workplace bullying and the illness.

Out of the 100 bullying complaints received between 2013 and 2017, only nine were investigated. None resulted in enforcement action.

“While no prosecution took place in those nine cases, you can be very sure that engagement and education did occur,” Urlich says.

Out of the nine bullying complaints deemed serious enough to investigate, four were from the healthcare sector.

“Our response to any incident or allegation must be proportionate to the harm. Taking something through to a full legal processes must meet certain standards for legal prosecution,” she says.

WorkSafe were also notified by the Coroner of seven suicides in 2016 in which bullying may have played a part. They investigated three.

“Of those three, none were found to be directly attributed to workplace factors,” says Urlich.

At least two Bay of Plenty DHB nurses, who were suicidal after feeling bullied by the DHB, had their cases turned down for investigation by WorkSafe.

Similar stories have emerged on the New Zealand, Please Hear Our Voice Facebook page where more than 46,000 members share their stories about working in the healthcare sector. One anonymous nurse posted in the group that they had “recently plucked up the courage to report the terrible bullying that is happening in our hospital to worksafe NZ.”

“It was very descriptive and identified that we had suicidal members of staff,” they wrote. WorkSafe responded, letting the nurse know that they would not investigate the complaint.

“I feel so incredibly gutted at the half hearted reply and the fact that he didn’t class my report as being serious enough to warrant intervention? If we are not protected by WorkSafe what do we do next?”

“You are meant to care for people … not drive them to a point of being broken and wanting to commit suicide.”

Sarah Jones* stood on the roof of Tauranga Hospital and thought about jumping. What stopped her was the thought of injuring herself and ending up back inside the hospital surrounded by the people she felt bullied by.

Jones is a nurse with 20 years’ clinical experience who has worked at the Bay of Plenty DHB for five years. Since February she has been on leave and is terrified of returning to work.

A lawyer recently looked into her claims of bullying and found there were no substance to the allegations. He was paid almost $9000 by the DHB for his work.

Jones had been struggling at work for some time after she was put on a “performance improvement plan”, suggested by her union representative, because of issues raised by her manager. She didn’t feel the criticism of her work or the performance plan were fair but was reassured it was “low level” and would be over quickly, she says. The processes went on for much longer than she expected and she wasn’t given the support she was promised, Jones says.

Jones dropped her union representative and sought the help of an employee advocate. The Wireless obtained copies of multiple emails where Jones’ advocate told the DHB that no meetings should be held with her without his presence.

During this time Jones’ mental health declined. She struggled going to work, despite having never had problems in her workplaces in the past, she says. At her lowest point, Jones considered killing herself.

“The Gorge is a section of road that goes between Tauranga and Rotorua and there’s been quite a few deaths on the Gorge through car accidents. There are places to go off. That was my thought most nights and mornings going to work. Every single day.”

One afternoon while treating a patient at work, Jones’ manager approached her about having a meeting. Jones explained that she had only been told about the meeting the night before which hadn’t left her with enough time to inform her employee advocate. She said she wouldn't attend the meeting without support.

Despite this, the manager then sent another nurse to cover Jones’ patient so she could attend the meeting. Distressed at being pushed to attend without her advocate, Jones called her counsellor who booked her in for an appointment that day. She stood on the roof of the hospital crying, feeling broken from her experience at the hospital over the past few years.

When she went to inform management she needed to leave to attend a counselling appointment, she was led to a room by a manager where another three members of management and HR were waiting. The door was shut behind her and she was told to sit down.

Jones was visibly distressed. She repeated that she didn’t want to talk without her advocate but the management team continued to talk at her.

“I was coerced into a meeting that was meant to be cancelled,” she says. “These are meant to be managers with experience who very clearly and blatantly ignored the situation.”

The next day, her doctor signed her off work on stress leave. She hasn’t been back to work since.

Jones felt abused and doesn’t believe the DHB are taking any responsibility for their actions. “They clearly failed to care for a staff member and failed to follow DHB standards.”

The lawyer hired by the DHB looked into the meeting Jones felt ambushed into. He concluded that meeting was “unfortunate” and recommended the CEO Helen Mason apologise.

Jones’ employment advocate told The Wireless that it was the first time he’d ever come across an employer who intentionally continued a meeting with a client after specific instructions not to do so without support present. He was shocked and angry.

Earlier this month Mason sent Jones an apology letter, calling the incident “a most regrettable situation” which was not intended.

“[I’m] frustrated at the lack of insight that you demonstrate," Jones wrote in a response to the CEO. “As a place of wellbeing, you are meant to care for people and make them better, not drive them to a point of being broken and wanting to commit suicide.”

Jones says there is a high turnover in her unit, with many nurses leaving as they feel stressed and bullied. She remembers the trauma of treating a Tauranga Hospital nurse who had attempted suicide, she says.

The DHB wrote to Jones last month saying she needed to return to work, despite her doctor's certificate suggesting otherwise. They noted that the “medical certificates supplied to date do not provide sufficient information for the DHB to be able to understand the disability”. They asked Jones to “provide more information so that this can be understood”.

Her advocate maintains it’s not safe for Jones to return to work.

“The DHB need to acknowledge there’s a problem, a serious problem, that’s costing them quality staff”

Stories of staff feeling bullied at the Bay of Plenty DHB first surfaced in news reports in 2014. Former Tauranga MP Brendan Horan spoke out about bullying at the time, and now says the DHB are continuing to deny what’s going on.

“A number of cases were brought to me in my office and they were really disturbing,” he says.

“There was one instance when a nurse committed suicide. Part of what contributed to that was the bullying culture at the hospital.”

Horan says a rampant bullying problem is being swept under the carpet. “The DHB were in butt-covering mode and they still are.”

“The problem is there are serious consequences for people blowing the whistle. I’ve seen it,” he says.

“The DHB need to acknowledge there’s a problem, a serious problem, that’s costing them quality staff.”

The Bay of Plenty DHB policy stipulates that “all workers have a right to a safe workplace,” and “all acts of violence, threatening behaviour, bullying and harassment will be dealt with in a consistent manner”.

Mason says the DHB has investigated all the cases uncovered by The Wireless and the recommendations "were taken seriously and were actioned, including apologies being made where appropriate".

Bullying is among the most severe sources of stress and can trigger complications like hypertension, autoimmune disorders, depression, anxiety and PTSD.

One study revealed that at 18.4 percent, the New Zealand healthcare sector has one of the highest rates of bullying in the country. Nurses are particularly affected, with researchers worldwide saying 65-80 percent have experienced or witnessed bullying with over half of incidents going unreported.

While bullying is troubling in any industry, it is particularly troubling in the health sector where it has been shown to compromise patient safety.

Haydn Olsen, a leading New Zealand researcher and consultant in workplace bullying, says he’s aware of bullying problems at the Bay of Plenty DHB. He says most district health boards in the country are struggling with bullying.

“Bullying thrives in a culture of silence where the perpetrators are deemed untouchable.”

Perpetrators get away with it all the time and that creates a “sick, toxic culture”, he says. He notes that DHBs often have complex, hierarchical structures that can muddle the process.

“Things aren’t dealt with early on. They’re left to fester and get worse. The cost of not doing anything far outweigh the cost of implementing early intervention. Instead of an ambulance at the bottom of the cliff, we need a fence at the top.”

JEREMY AVIS

The full story

When Mary Avis talks about her son, her eyes well up but she doesn’t cry. She doesn’t want to be sad anymore, she says. She wants to remember her only son, Jeremy Avis, as the person who bought her more joy than anything else in the world.

“From the moment he was born, I loved him greatly. There was a bond between him and I, I still feel it now. I just feel so lucky that I had that wonderful love that some people never experience,” says Mary.

Jim Avis, an ex-navy man with a gentle nature, doesn’t hesitate when describing his son as “too good to be true”.

“As a young boy he was quiet, he could be left to his own devices, and he was loving.”

Jeremy Avis, like his dad, was a gentle man. He was happiest when he was outdoors, paddling his kayak at Omokoroa Beach, taking long walks through Te Puna Quarry park, and riding his mountain bike on tracks in Rotorua. His parents joke that his bike collection cost as much as their car.

Avis’ suicide in 2016 shook the Tauranga medical community. Nearly two years after his death, colleagues and patients are still telling his family stories about him. His parents recently learned that he had taken leave from work to help care for a friend with cancer, and his mother beams as she explains that her son was never too important to make his patients a cup of tea.

“That was the kind of person he was,” says Mary.

But their memories of Avis are dampened knowing he felt mistreated at the Bay of Plenty DHB. They are still without answers as to why nothing was done to support and protect him at Tauranga Hospital when he was assaulted by a coworker and felt bullied by a manager.

After his death Avis’ sister, Kim Audas, requested his personnel file from the hospital, hoping to get answers. She says the family were handed a manila folder with her brother's CV inside.

“We don’t need his CV,” she says. “We do want answers and we do need to have them. We are entitled to that so we can move forward.

“I don’t want any more nurses from that hospital to commit suicide.”

When Jeremy Avis arrived home from living in the UK, his reputation preceded him.

“I had heard this awesome nurse had come from London. He’d done heart valve replacements all over Europe and in neonate for prem babies. He was very knowledgeable, a fantastic nurse,” says Tessa Pedersen, a former nurse at Tauranga Hospital.

Pedersen and Avis became close friends while working together, and kept in touch after Pedersen left the DHB. She spent five years at the hospital but was fed up with management which she says left her feeling belittled and demeaned. She’s been working as a nurse in Australia ever since.

The pair weren’t the only ones who felt bullied; another nurse felt so badly treated, says Pedersen, that she was worried about the nurse’s mental health.

“Tauranga [Hospital] says it has a zero tolerance to bullying. That’s crap. An utter load of crap,” she says.

Pedersen, as well as a hospital orderly, was in the room when Avis was struck hard across the face by a coworker.

“She marches up to him and absolutely boof! Straight across the face. I just stood there with my mouth wide open. I was in shock.”

The reasons why the coworker hit Avis are not entirely clear but according to Pedersen, it was because of a disagreement about the order of patients on a whiteboard.

“She was screaming at him, ‘did you not hear what I said!?’,” says Pedersen.

“He had a big red welt by his eye and down his face. If it was him that had hit someone, the police would’ve been called.”

Pedersen took a photo of Avis’ face on his phone and says he also complained to the head of department, who took a photo as well.

After work that day Avis went to his parents. His mother, Mary, says her son was reeling from what management had told him.

“When he came at five o’clock at night the marks were still on his face. It wasn’t just a slap,” says Mary.

Avis didn’t hear anything from the DHB about the assault so a few weeks later he approached HR, says Pedersen.

“They said, ‘oh look, she has a [medical] problem’.”

No investigation, no apology, nothing, she says.

Avis isn’t the only one. A former employee of the Bay of Plenty DHB told The Wireless she was shoved by a manager while working at Tauranga Hospital. Despite complaining, she says nothing was done.

Avis’ sister still struggles knowing the DHB did nothing about the attack on her brother.

“When you have someone come to you who has been assaulted … People need to be held accountable for their actions,” says Audas.

“As his sister, I would like her to be held accountable for her actions. I would like for it to be on her record.”

A year before his death, Avis wrote to Pedersen saying he wanted to seek help from the union but he and another colleague, who felt bullied, were worried that they would be seen as troublemakers by the DHB.

“Like me she is wary about approaching [the union]. I really need a job,” he wrote. Avis was the breadwinner for his family and his wife was pregnant with their second child.

Pedersen says Avis felt stuck. “Jeremy had nowhere to go.”

Avis’ family and Pedersen say a 2014 incident completely eroded his self-worth. He was escorting a patient, following a procedure, between departments when the patient's heart rate suddenly plummeted. According to what Jeremy told Pedersen and his parents, a junior doctor, who was present, froze so Jeremy acted quickly. He put up a bag of fluids and injected a medication.

“He saved that patient’s life,” says Pedersen.

But technically, Avis had not followed protocol, which stipulates that a doctor should administer the medication. He immediately went to his superiors to tell them what he had done.

His mother said he stopped by after work and told her what had happened. He was worried. Mary told him not to stress; while he hadn’t followed protocol, at the end of the day he’d saved someone's life.

“Wasn’t that more important?” says Mary.

“He told us the family [of the patient] just thanked him, couldn't thank him enough. They hugged him and said, ‘thank you for saving our dad’.”

However the DHB decided Avis’ actions warranted a formal investigation. He was put on six months' supervision, during which he was restricted to working in a single department and wasn’t allowed to do the nursing tasks he loved, his parents say.

“He was made to do the worst jobs,” says Mary. “They didn’t treat him as a human being, I felt, with any dignity.”

Pedersen says Avis was devastated. “That’s when I noticed a decline in his mental state,” she says.

In an email to Pedersen, Avis wrote that the hospital had recommended he leave the department after the supervision period ended. “I want to put a file together about the things that have happened to me while working in the dept,” he wrote in an email.

His sister says she believes Avis wasn’t supported by the DHB.

“That really was his demise because 20 years of nursing was challenged and he was further belittled,” says Audas.

“I don’t want his death to be in vain. He won’t be the last one.”

Avis left his job at Tauranga Hospital in early 2015. He started a job as a medical equipment sales rep but the commission-only income put huge financial pressure on his growing family.

Troubles with his neighbour were also affecting him badly. The Coroner’s report notes that Avis had been to his GP complaining of anxiety due to “significant life stresses”. He had organised a mortgage repayment holiday for six months.

Jim says Avis’ time at the DHB left him unable to cope. “He would usually have flown through those things,” he says.

A month before his death, Avis drove himself to mental health services at Tauranga Hospital and was assessed by the crisis team. He was discharged a short time later and referred back to his GP.

Avis left the sales job and accepted a position as a nurse in another department at Tauranga Hospital, but two weeks before he was due to start his wife found him dead.

“I know, deep down in my heart, it was the DHB that sparked this. It all started with the DHB. The last lot just tipped him over,” says Pedersen.

Avis’ funeral was themed as a party for his daughters so they wouldn't grow up remembering it as a sad event. His first-born was about 2 years old and his youngest was only 8 months old. There were pink helium balloons on his coffin, pink table cloths, and flower arrangements on all the tables.

“There were presents for his girls, wrapped with big pink bows, in celebration of their daddy’s party,” says Mary. “She’ll always remember her dad’s funeral, not as a sad thing, but as a party.”

The church was packed and some guests who arrived late had to stand outside. Pedersen was on her way to New Zealand when she got the news of Avis’ death. She missed his funeral by two hours.

Kim Audas is still desperate for answers. She sits in the lounge of her Ngongotaha home and reads her brother’s Coroner’s report for the first time.

“I feel let down. It is totally unprofessional and unjust to let a suicide go when we know he was bullied.

“The DHB really had a responsibility to my brother … What is there for nurses who are being bullied? What support is out there?”

Pedersen is speaking out not only for Jeremy, but other nurses who feel bullied. She says using her full name might mean she never gets a job in nursing in New Zealand again but she doesn’t care.

“I don’t want his death to be in vain. He won’t be the last one.”

Allan Halse, director of CultureSafe New Zealand, says the number of people coming to him with stories of workplace bullying is growing astronomically.

“The number of clients we represent has doubled every year since 2014 to the point that we are dealing with between 200 and 300, mostly bottom-of-the-cliff, cases each year.”

He says about 25 percent of his clients have considered or attempted suicide. “Seventy five percent of our clients have been prescribed antidepressants, sleeping tablets, or other medication. Fifty percent have been diagnosed with depression, anxiety or PTSD,” he says.

“Neither the DHBs or government understand what workplace bullying is or the serious emotional, psychological and physiological harm that it causes.”

A former Bay of Plenty DHB employee who worked closely with managers says poor management, not bullying, is the biggest issue.

“There are some great managers but also many that lack the knowledge, skills and temperament to manage competently.

“Due to the lack of skill in handling complex employment problems, managers can often feel like getting rid of the person so the problem will go away. I saw that issue a lot. A significant amount.”

The former staffer says people who are moved into managerial roles are often not given enough training to be effective, making it difficult to ascertain whether bullying or poor management is the real problem.

“It was very rare therefore, in my opinion, that there was targeted bullying [at Bay of Plenty DHB]; someone intentionally pulling an employee down deliberately and on an ongoing basis.”

When a staff member uses the world “bully”, a line in the sand is drawn and managers get defensive. Without the necessary skills to deal with the claims of bullying and managing, general managers can severely botch up the process - even when the complaint may not be true, says the former staffer.

“Staff confidence, morale and therefore their effectiveness in their roles can be undermined, both individually and collectively, or in some cases be destroyed by a manager who just didn't know how to manage.”

Allan Halse from CultureSafe agrees that ineffective managers are part of the problem but that’s not necessarily different from bullying, he says.

“What is being confused here is an issue of intent. Yes, the manager might be incompetent and not intend to bully, but they do. Their behaviours are still bullying behaviours.

“We have a perception that bullies are outspoken, loud and obvious in their bullying tactics. Probably worse is a bully who carries out covert behaviours because it’s ongoing, subtle, and often there are no witnesses to it.”

He says managers who allow the behaviour to continue are culpable in any deaths of their employees. “You've got employers who are condoning behaviours that are leading to people killing themselves.”

“New Zealand is extremely unsophisticated when it comes to dealing with workplace bullying and it is time that the government and the DHBs stepped up.”

*Not her real name.

This story previously included a line that said the "Bay of Plenty DHB has repeatedly denied the organisation has a bullying problem". This was inaccurate and has been changed to "The DHB has previously denied allegations that it condones bullying".

Reporting by Mava Enoka

Edited by Veronica Schmidt

Videography by Luke McPake

Photography by Luke McPake and Rebekah Parsons-King

Design by Rebekah Parsons-King

Art direction by Dave Wright

Development by Van Veñegas

Where to get help:

Lifeline: 0800 543 354

Suicide Crisis Helpline: 0508 828 865 / 0508 TAUTOKO (24/7)

Depression Helpline – 0800 111 757 or free text 4202