BROKEN BAD

A country in the grip of meth

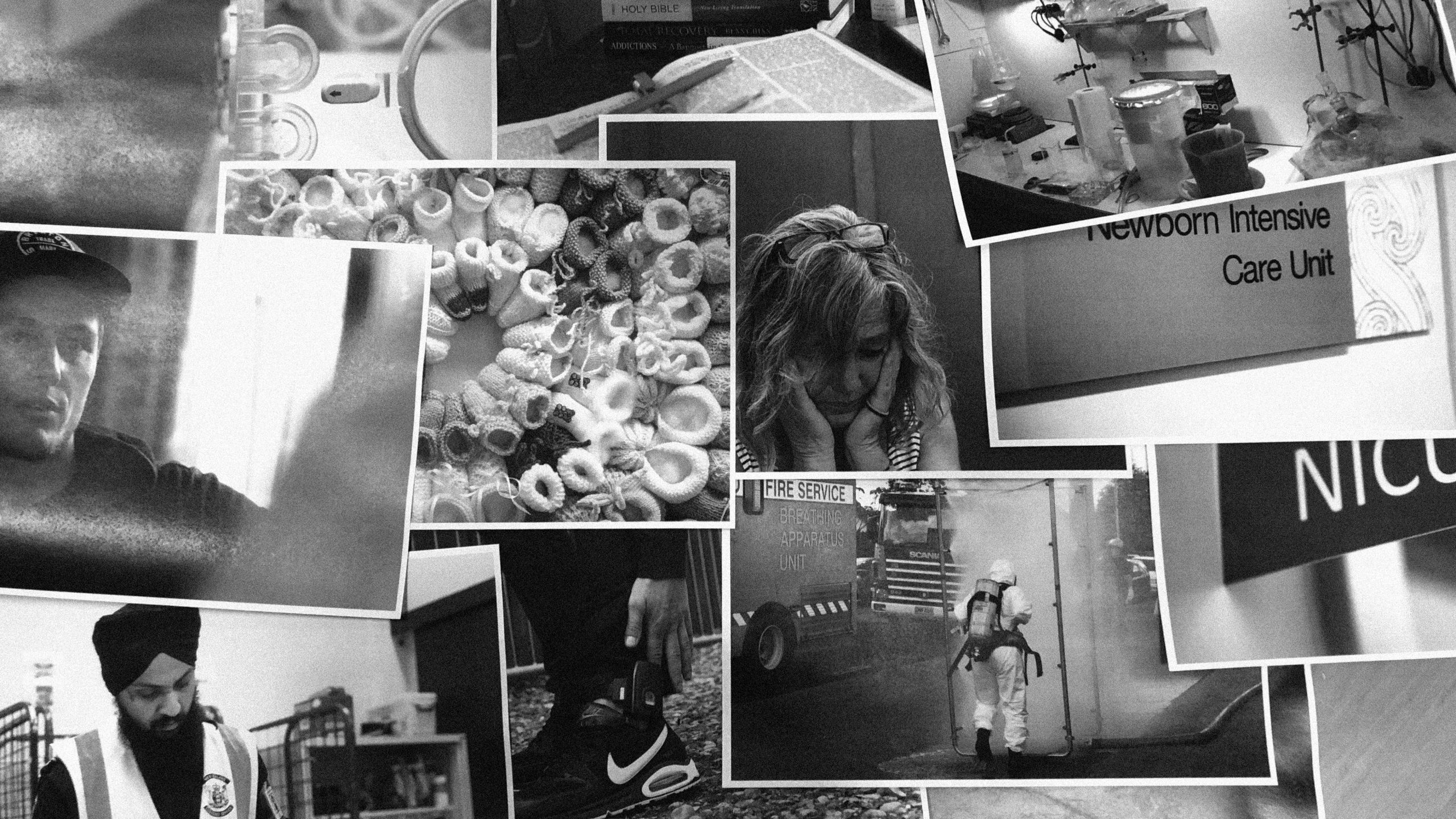

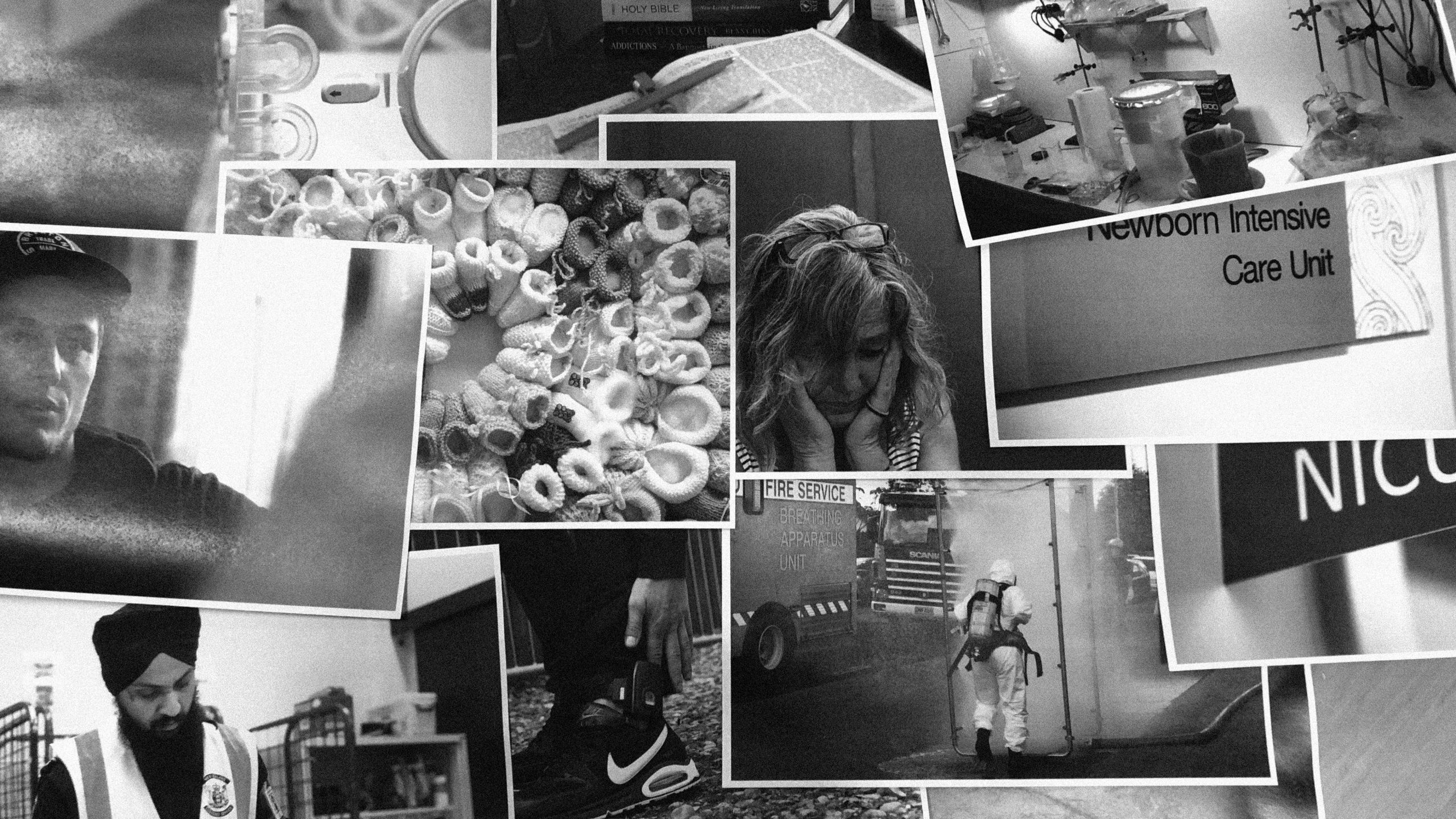

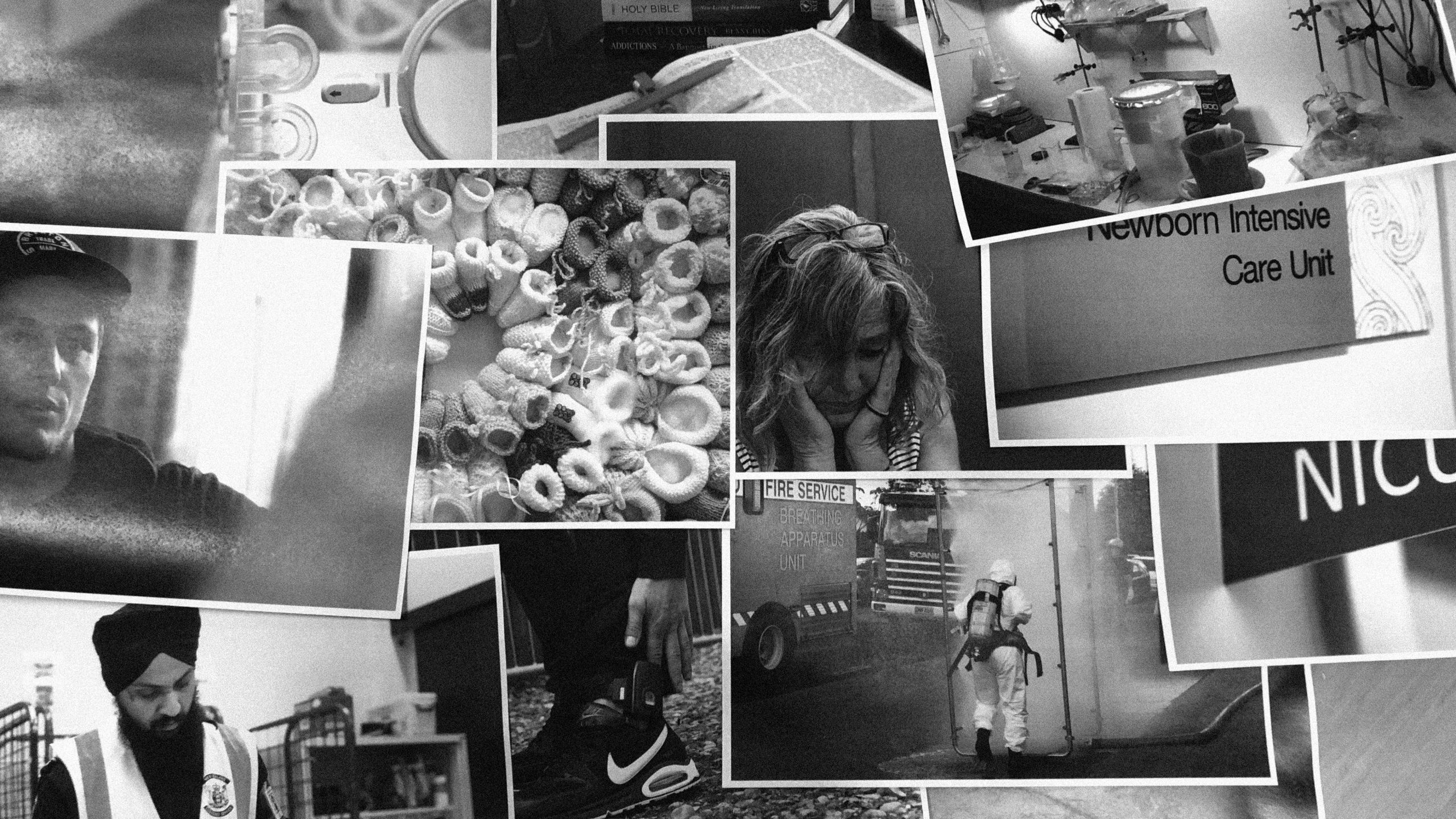

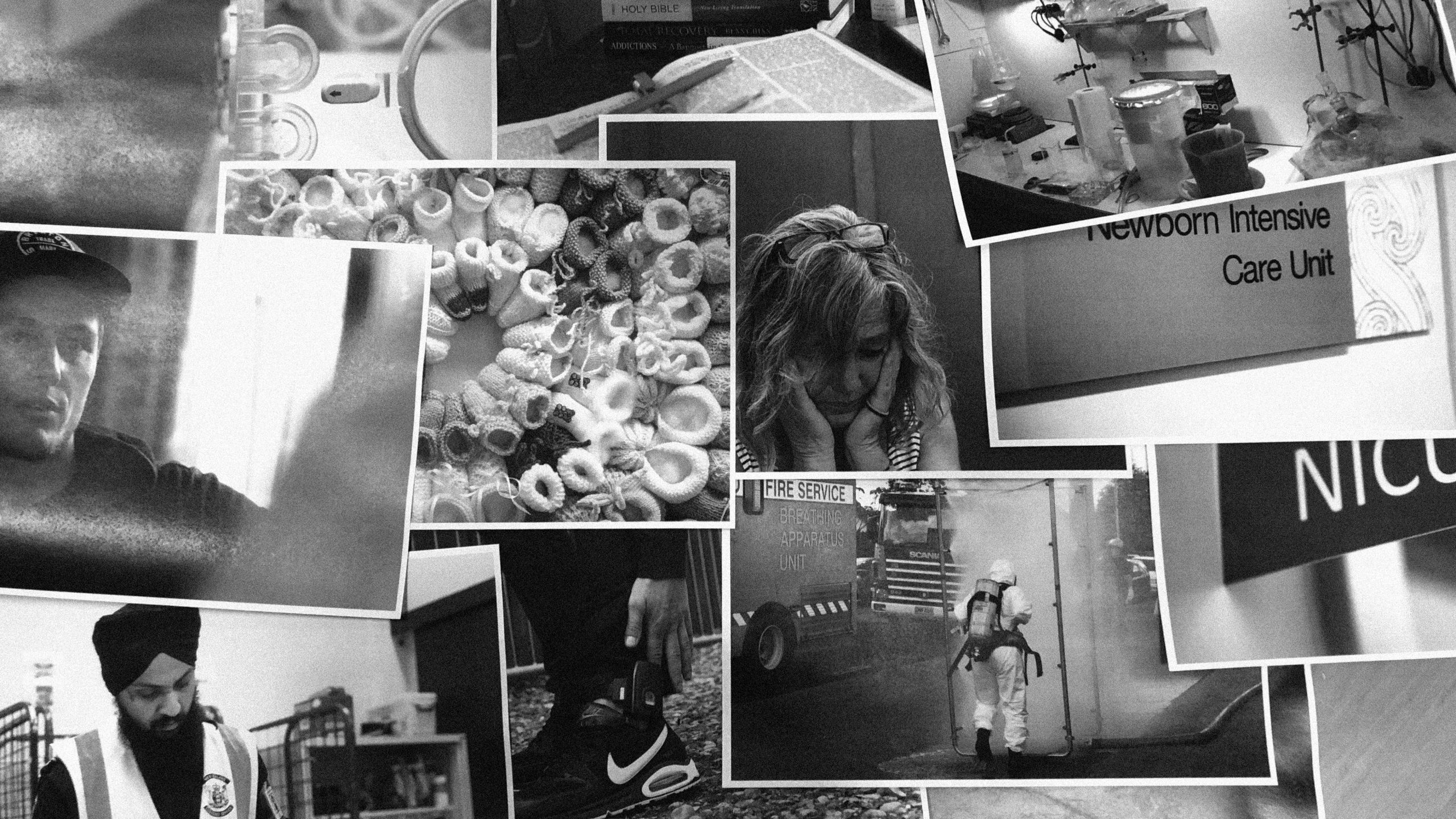

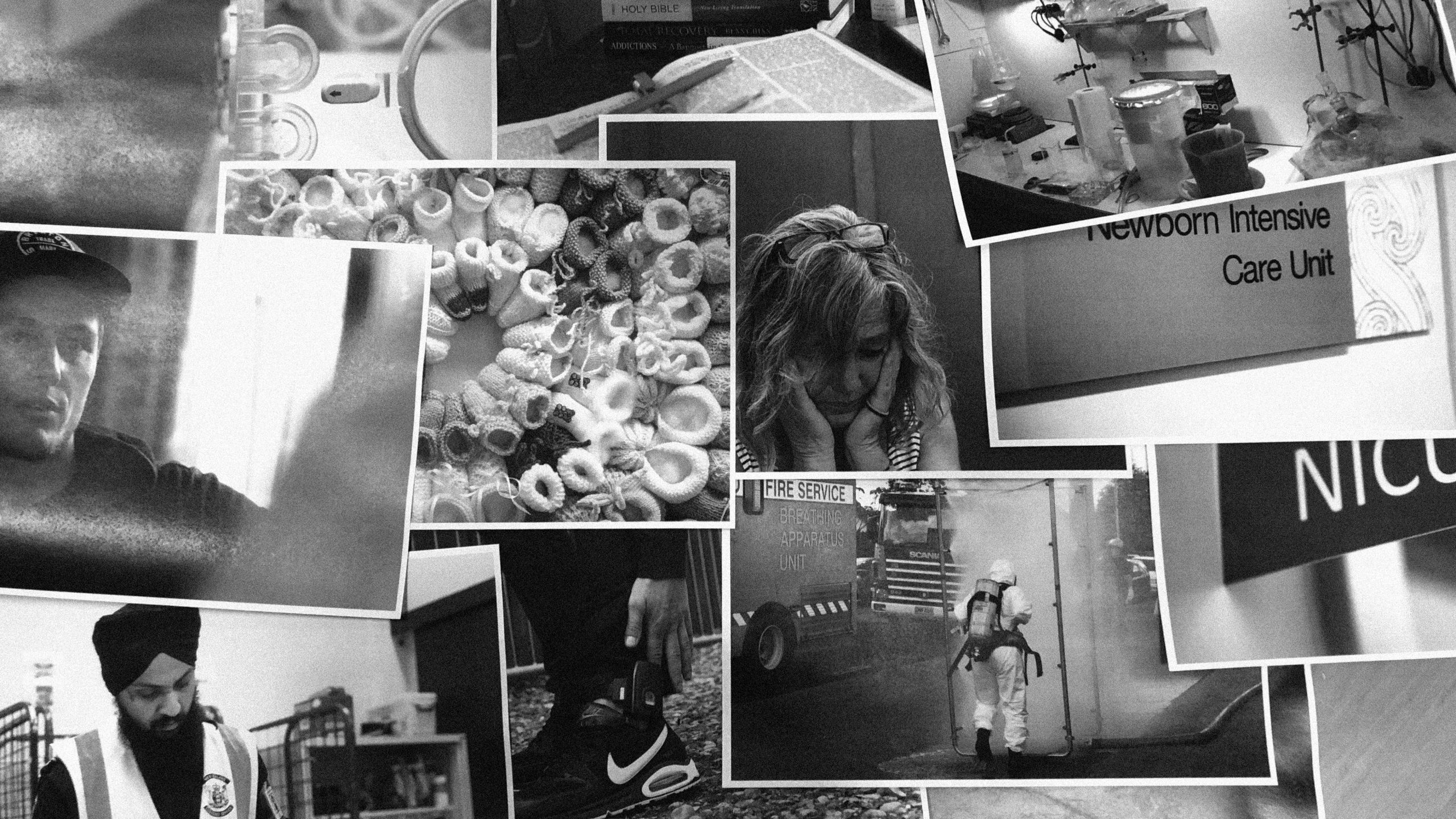

A baby survives on Milo. A woman has her teeth knocked out. A grandfather avoids his own home. RNZ sent reporters and visual journalists out across New Zealand to chronicle daily life in a country teeming with methamphetamine.

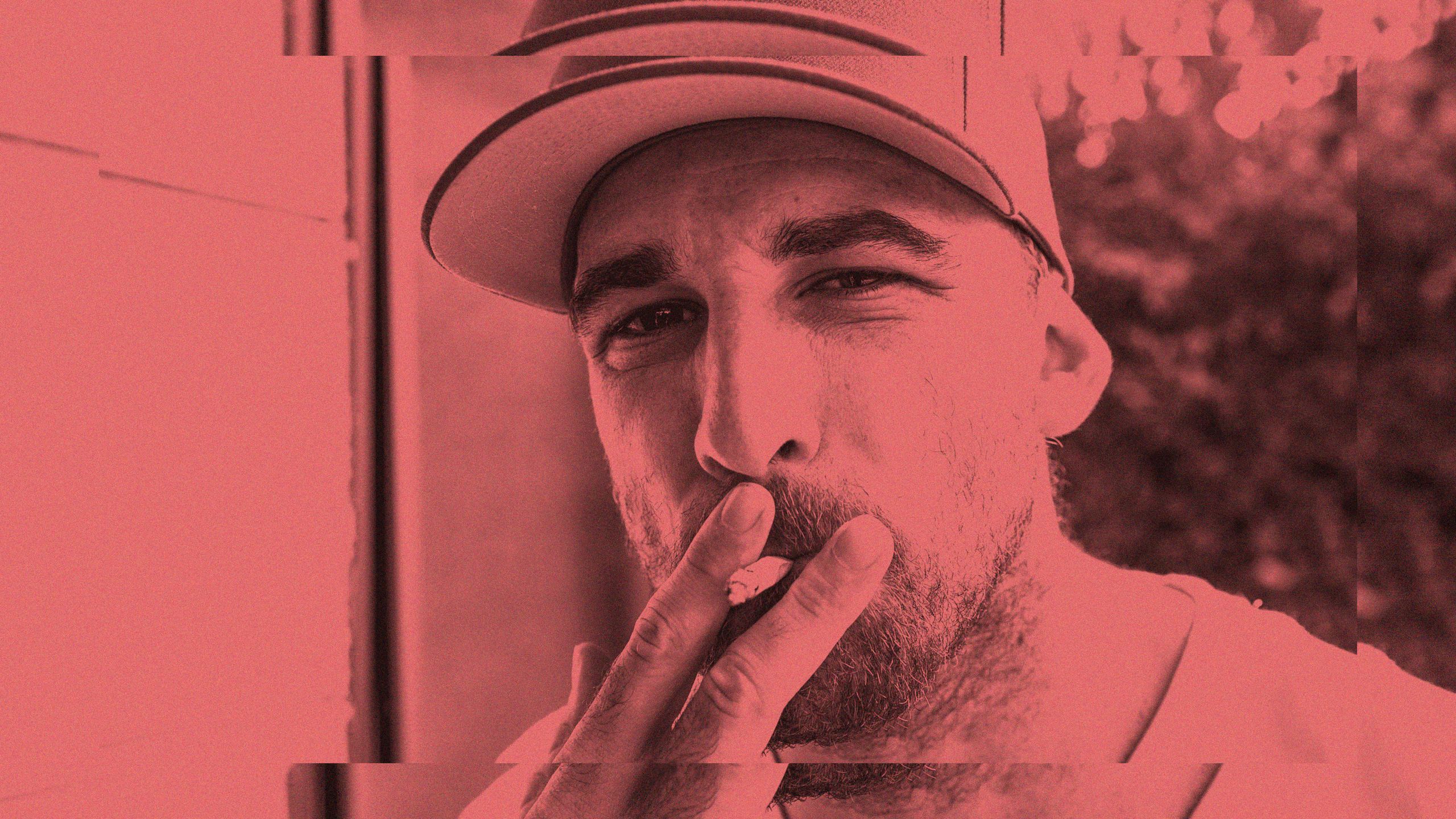

Sweat has yellowed the collar of Norm’s* white shirt. The smell of a big night wafts from the knitted sweater he wears over top as he chats to two women smoking outside the Auckland City Mission.

Beside them, curled up on a pavement pock-marked with old chewing gum, a woman dozes beneath a sleeping bag.

Norm can’t remember what he’s doing here this morning.

“I’m not sure. I’m a bit lost today,” he says.

“I ran into someone who gave me a blast last night.”

His skin is pale, his eyes, framed by the wrinkles of middle age, are wide and fix for long periods on something in the distance.

He reckons he’s okay though, because he slept last night.

“It wasn’t very strong.”

Once he was awake for a few weeks and ended up in a “very fragile state”, but that was when he was using methamphetamine (meth) every other day.

His eyes are fixed on a wall to his left.

“I’d prefer not to take it at all,” he says.

Pam, 77, winces as she lowers herself into an armchair.

"Arthritic knees," she says. They won't give her new ones until her dodgy hip's been replaced.

"I feel 100. But there was no way I was going to let CYFs take my grandson."

She hobbles around her Northland home after the 9-year-old, who suffers from ADHD.

"He's a lovely bright little boy. But he's exhausting. He doesn't walk, he runs; he's really loud; he sniffs out alcohol so I can't have it in the house; and he'd stay up till 1am if I let him.”

He was a ‘P baby’, born to Pam’s daughter, who used heavily throughout her pregnancy.

Pam brought him home from the hospital when he was a 1.8kg (4lb) newborn with a cleft palate and a cleft lip. When he wasn't asleep – which was most of the time – he screamed.

Pam's daughter was in the mental health ward and unmoved by the baby’s pitiful condition. "Shit happens," she said, according to Pam.

Tears roll from Pam’s eyes.

"There's no hope for her. She's fried her brain. You can tell from her speech. She was a beautiful, brainy young woman.”

Crates of parcels and envelopes marked with yellow “suspicious” stickers line the cramped Customs room that backs on to the mail warehouse near Auckland Airport.

Johar opens a package: football boots, a T-shirt and a bottle of gum. He throws a Customs flyer into it, tapes the package up and biffs it onto a pile of mail for delivery.

"We don't always find something but it would be hard to go a day without finding meth."

Johar’s eyes check over the mail rolling along a belt through a scanning machine.

A year ago he quit his job at a supermarket, swapping a checkout conveyor belt for this mail belt.

He’s seen a lot of meth since then, his biggest find coming just before Christmas.

"It was December 23rd, 1kg of meth hidden in toys – I still get a buzz thinking about it – I stopped that from hitting the streets."

Nearby an officer rips open computer hard drives from China full of cigarettes.

In the corner an officer, wearing a mask and gloves that stretch to his elbows, opens a white envelope bound for Christchurch and finds a small, clear bag of white powder.

He grabs a scanner the size of an eftpos machine and puts the bag up against its laser. Methamphetamine, the machine's screen reads.

"It came from the Netherlands and the name and address are typed, so this was probably ordered off the dark net," the officer says.

Johar doesn’t bother looking up. Neither do any of the other officers.

It’s too small an amount for Customs to investigate. Instead it will go to local police.

The officer drops it into a box labelled ‘Christchurch’. It teeters on top of a pile of other envelopes and packages.

PURE FACTS

Methamphetamine (meth) is a class A drug with nicknames to burn – P, pure, crystal, crack, ice, yaba, goey, crank and Tina – and can come as a powder, crystals or liquid.

The glass pipe, sometimes called a glass barbeque, has become a symbol of meth use, but the drug is not always smoked; it can be swallowed, snorted or injected.

A stimulant, meth prompts the central nervous system to release a rush of dopamine that can make users feel confident, energetic and alert. It can also increase libido and decrease appetite.

Large doses or long-term use can cause insomnia and anxiety as well as psychotic symptoms, such as agitation, delusions, hallucinations and paranoia.

Heavy users often drop large amounts of weight and suffer from ‘meth mouth’ (severe tooth decay and tooth loss) and skin sores. P can also damage the liver, kidneys and lungs and an overdose can cause heart failure.

In withdrawal, addicts are usually very fatigued, sleeping for long periods; and can suffer from nausea, depression and anxiety.

Meth is either imported in crystal form or manufactured (“cooked”) in clandestine drug laboratories, known as clan labs. Ephedrine or pseudoephedrine, found in foreign-made cold and flu medication, is needed to cook. Cooking meth is dangerous, as poisonous, explosive, corrosive, toxic and flammable chemicals are used.

“I think I should switch to chardonnay,” Clare* says.

She puts her empty beer on the courtyard table and darts inside her central Auckland office, emerging into the late afternoon sunlight with the wine in one hand and gesturing wildly with the other.

“People used to frown on it ... when it was all ‘P epidemics’ and ‘what’s-his-name with the samurai sword.’”

She plops back down in her chair and lights a cigarette.

“It got to the point that because the cocaine in New Zealand was so shit people were like, ‘Anything that’s white is all right.’”

Years ago Clare, 33, went to rehab for alcohol addiction but she works in advertising, with its fabled socialising, and that doesn’t lend itself to sustained sobriety. She started using meth so she could stay out longer at night and still work hard.

“Rather than being a sloppy drunk, it balanced me out.”

Now it’s dropping her into spirals of panic attacks, self-harm and depression. Last year she asked for help. She’s still on a waiting list.

She tops up her glass and finishes a description of a typical night out.

“All of a sudden you’re like, ‘Whoops, it’s five o’clock in the morning. Do I go to sleep or do I just charge on through?’ So you have a shower, then you have another couple of lines, then you don some clothes. Then you think, ‘F***, if I’m going to check my emails I may as well head into the office at seven.’ So you’re in there and shots for breakfast are very acceptable after a big night. Then you hit the slump at 11 and you go, ‘Well…”

She lights another cigarette.

“A dear friend of mine said, ‘A smart person always saves a little bit for breakfast.’”

Emergency departments, mental health units and drug treatment programmes are all recording an increase in patients with meth-related problems. The number of people referred to Auckland’s regional drug and alcohol services quadrupled between 2008 and 2017.

Simon* lies back in the prison dental chair, clasps his hands together and opens his mouth.

Where his top front left tooth should be there is a pink, concave patch of gum. Next to it is the rotting stub of another tooth.

The dentist, who visits Auckland’s Mt Eden prison twice a week, grabs a mirror, and puts her gloved hands into his mouth.

“We’ve got several of the molar teeth – literally all we’ve got left are the roots,” she says.

She pulls at the corner of his mouth and reveals more toothless stretches of gum.

“We’ve lost three or four when he broke his jaw.”

Simon is 32 and has “meth mouth” from using P for 15 years.

The dentist removes her hands from his mouth.

“It’s in the early mornings, when you can’t get your hands on painkillers – it’s pretty intense. I’m awake for hours. It’s one of the worst pains I’ve ever had,” Simon says.

Sometimes he puts paracetamol pills straight into the holes in his teeth.

“It’s not really designed that way,” the dentist says.

Simon’s grandmother has just died. She left him money to have his mouth overhauled once he’s clean.

In the next month, he’ll have most of his remaining teeth pulled out.

“I don’t like needles, let alone in your mouth,” he says.

He stares at the ceiling.

Click here for the Broken Bad investigation, Insight: Imprisoned by meth.

Two out of three imprisoned drug offenders are inside because of a meth conviction.

Frith Palmer steps up to speak. The mic stand is slightly too high so she tilts it as low as it can go and starts in a strong, determined voice.

"We've got that scourge, the P scourge running rampant. Unfortunately P, alcohol, gambling… These poor kids, they go home and there's no food. They go home, there's a punch up.”

Heads nod and a chorus of “Kia ora” rises up in the Flaxmere Community Centre, encouraging her on.

The small crowd is here lamenting the rise of unruly, unsupervised children, after a group of teenagers were arrested following the killing of local man Kelly Donner, 40.

Frith, a mother of three, moves closer to the mic as the rain beats on the roof of the hall.

"They go home and mum and dad have been on the old glass barbeque all bloody day. What have they got? Nothing.

"So they're all gathering. That's their new family. Oh, they feel mighty. But it takes one person to break them.

"If we band together, these kids, they're going to have someone. We could all take a piece of these kids and give them mana.

"Like hell am I going to let these kids run us, and run our generation out of what we love. This is our home."

Read about how schools are grappling with the rise of 'P babies'

The last of the white crystals stubbornly cling to the sides of the plastic bag. ESR scientist Aimee Lloyd pokes a little metal spatula in and starts scraping. The silver bracelets on her right wrist clink together as she coaxes them out.

“They’re sticking because they’re damp,” she says. “It’s the solvents left over from the manufacturing process.”

This is a small hitch as ESR drug technicians’ problems go. The scientists, who analyse substances for police and Customs, are up against meth smugglers’ increasingly innovative concealment methods. In recent years, they’ve had to figure out how to separate meth from the highly-flammable fluid of lava lamps and the liquid within dishwashing detergent containers so they can confirm the substance is P.

Aimee weighs the crystals – just under a gram – then carries them across the laboratory. She picks up a dropper with gloved hands and squeezes drops of a reagent into a dish.

“If it’s meth it will give an orange colour,” she says.

She lowers a crystal into the liquid. It’s like blood hitting water; rusty tentacles spread from the middle of the dish toward the edges.

Aimee looks at it. “If it’s strongly positive it goes red.”

Read more about how increasingly inventive meth smuggling is testing ESR

The prison van stops and Allan* steps out.

He looks up at the large brick house then knocks on the door.

He is dressed in the worn, blue shirt and poorly-fitting trackpants he was arrested in more than two years ago and clutches a handful of papers.

One of the Moana House counsellors hurries to the door and opens it, smiling.

“Is this the right place?” Allan asks.

Moana House is a live-in Dunedin rehab facility for male offenders. Three-quarters of the men are referred for meth problems and many of them are dumped on the doorstep with nothing.

Inside the strains of a Fijian hymn and the smell of chop suey permeate the house.

Programme director Claire Aitken looks over at Allan.

"That man has turned up in what he's wearing and that's it.

“There is a huge increase in people presenting with methamphetamine issues and generally it has been more destructive than anything else they had been using before.”

Claire heads back to her office to type another email. The house has a waiting list 142 people long and no funding past June.

“Chasing money is one of the biggest things we do,” Claire says.

“God, if I could just get on with the [rehabilitation] work it would be fantastic.”

Allan sits on a leather couch, picks up a ukulele and starts to strum.

Click here to read about Moana House’s funding crisis.

Dr Simon Rowley sits under the bright artificial lights of a sparse Auckland Hospital meeting room finishing a story: “We asked her why she wasn’t intending to breastfeed and she said because there was a P lab in her basement at home and she didn’t want to risk contamination.”

The consultant neonatal paediatrician settles forward in his chair.

That was an unusual case, he says. Mothers who use meth – usually along with other drugs and alcohol - rarely disclose their drug use.

Dr Rowley cares for one or two babies exposed to meth, usually in-utero, each month.

In some ways it would be better if he cared for more – babies often don’t start showing signs of meth’s impact until days or weeks after they’re born. By then, they’ve long since left the safety of the hospital and missed their early shot at help.

“I suspect we would see less than 10 percent [of babies exposed to meth],” Dr Rowley says.

He gets up and heads for the newborn intensive care unit. The lights are dim but cuddly cartoon animals brighten the muted walls: a tiger, a deer cuddled up with her fawn.

Click. A picture of a police officer walking through a decontamination shower. Click. Chemicals spraying up a wall. Click. Detective Sergeant Rhys Wilson hits the mouse’s left button again and up pops another scene the police national clandestine laboratory team have visited.

This time the shot shows a white bench covered in glass beakers.

“This is probably one of the more organised or professional scenes that I’ve seen from a cook,” he says.

“You can see he’s got all his lighting set up. He’s got shelves to hold all the individual equipment. [This is] someone who probably takes pride in their work, in their product.”

He smiles at his own grudging admiration, then his face falls.

“This was in the garage of a family home, with children living in the house.”

As team supervisor for the North Island, he’s seen some surprising sights – a lab set up in a cave in the countryside, an old milking shed fitted with a false floor to hide hundreds of litres of chemicals – but still, nothing shocks him more than finding children in labs.

“Sometimes one or both parents are using the garage of the family home to make the drug with no thought given to the harm that they’re doing to their children that are living there. Being exposed to that contamination, to those toxic chemicals.”

His hand moves on the mouse. Click.

A shaky video of a camper van appears, a garden hose connecting it to tank water, a hot plate lying on the passenger seat, chemicals stored in soft drink bottles.

“Obviously once the cook has finished using this vehicle in this way, he’s more than likely going to clear it out and try and sell it for money, so the poor person that ends up subsequently buying this has obviously no idea of what it’s been used for and what sort of contamination is in it.”

Stan* has just got out of the shower at work and thrown on a fresh T-shirt and pair of shorts. He almost always showers at work even though he has a decent shower at home.

He’ll eat out tonight too, like he does every night.

Any parts of his daily routine he can do away from home he does. It lessens the chance of running into his daughter, 29, who lives under his roof and dominates his mind.

His voice cracks as he talks about the five years since his daughter, who was studying in another city, came home to Tauranga for Christmas, bringing with her a boyfriend and a meth addiction.

“It’s like a huge nightmare… I get high blood pressure and need counselling.”

Her boyfriend is in jail now but she remains, along with her two children, who Stan does his best to watch out for.

She sleeps a lot but functions most of the time, he says.

At times, however, their lives spiral into turmoil.

“I’ve gone home sometimes to find the house trashed, holes punched in the walls,” he says.

“I am the only one who has time for her - no one else cares.”

Kahn Steiner stands in the Wellington church carpark chatting to people dressed in the same shirt as him, 'Anti-P Ministry' emblazoned across the front.

Laughter erupts as the group enjoy their break from an anti-meth training workshop talk. Kahn has a cheeky smile but when he casts his mind back to his childhood his face is stern.

"I was raised in a meth lab, I was a 6-year-old kid selling meth with my dad, while my mum worked as a prostitute in the clubs.

“By about the age of 15 or 16 I had become fully addicted to methamphetamine; I had learnt how to cook methamphetamine by the time I was 16," he says.

He looks at the ground.

"When I was on meth, I was robbing everyone or anyone, I didn't care who you were, all I cared about was getting fried."

Three years ago he quit and joined the anti-meth movement, but he hasn’t left P behind, he says.

"You never get out, you're either in the game or you're fighting against the game, the only way you ever get out is when you die."

He shrugs his shoulders.

Lindsey Foster sits on a worn, brown couch wondering what to watch on Netflix now that he’s burned through every season of Shameless and Weeds.

On his right ankle, between tattoos, is an ankle monitoring bracelet.

He’s been on bail, confined to this poky Whangaparaoa house, for more than a month.

“All my charges are due to my meth addiction,” he says.

Next week the 26-year-old heads to rehab, but after that he may be sentenced to jail. It will be his eighth time inside.

A tiny pink umbrella hangs on the open front door.

“My daughter thinks I go to work,” he says with a hollow laugh.

In the afternoons, he takes her to the park. Her school is next door, the playground right over the fence. He waves towards the back garden.

“I stand out there and watch her,” he says.

“I treat her like my little princess.”

Other than his 6-year-old and her mother – who has allowed him to be bailed to her home – he sees one person.

“She’s my only friend.”

He can’t see anyone else, he says.

“They don’t understand what I’m going through and how I’m trying to change my life. They’re just going to offer me drugs and I’m probably going to be weak and just take it.”

LINDSEY

“My mum’s just about cut me off”

Here’s Lindsey Foster’s meth addiction in numbers: eleven of his 26 years spent using; seven stints in prison; a five-page-long criminal record; $200 a day spent on meth; 15 cars seized, lost or sold to fund his habit; three weeks awake in one stretch; access to one of his four children.

When he first tried meth as a 15-year-old on Auckland’s North Shore it made him feel invincible.

“It was pretty amazing really, like nothing else mattered,” he says.

It was the perfect feeling for a teenager who had just been kicked out of high school, become a father and watched his parents split up.

“All the emotional stuff I was feeling, I just buried it.”

His problems grew – an acrimonious access dispute erupted over his children – and so did his meth use, building from a smoke once or twice a week to injecting every day.

It gave him sweet but short relief, then created new problems. He needed money to fuel his addiction and begged, borrowed, burgled, lied, stole and cheated to get it. He gained a criminal record and lost friends.

His sister stood by him, his father offered him chance after chance at his mechanic’s workshop (“I kept screwing it up”) and his mother gave him help until it nearly ruined her.

“My mum’s just about cut me off. She’s got multiple sclerosis and all the stress I’ve caused her over 11 years has made her sicker.”

Any anger they felt couldn’t match his own, though. He was lost in fury at being separated from his children and lost in the addiction he denied he had but that was ruling his life.

He didn’t want to take his anger out on his girlfriend so he attacked himself, smashed in his own face, gave himself black eyes.

Addiction melded with depression. He attempted suicide. He was found before he died and life went on much as it had before.

He went to jail, got out, went to jail, got out. He got clean, slipped back into addiction, got clean, slipped back again.

For a while he was homeless, living on the streets of central Auckland.

It’s only now, 11 years after that first smoke, that he can see how meth pillaged his life.

“You don’t know that it’s ruining your life until it’s too late.”

He’s been clean two months and wants to stay that way, but he’s afraid the grip meth has on him won’t ease even after he’s completed rehab.

“I’m going to move out of Auckland. I have to … because if I stay here, I’ll be back at it,” he says.

“I just want to get a job and live a normal life and make my daughter proud.

“I’m sick of it – 11 years of an addiction and I’ve got nothing to show. I’ve only got a little bit of clothes, a few shoes.”

Kathryn Leafe opens the van and sunlight bounces off a collection of yellow bins, plastered with ‘infectious substance’ labels.

She clambers in among them.

Every fortnight the van, operated by the New Zealand Needle Exchange that Kathryn heads, leaves Christchurch and heads for the West Coast to discreetly deliver clean needles and health advice to drug users, and to collect their used syringes.

Kathryn talks quickly in an East London accent – she was born on the West Coast but spent her formative years in the UK – about how rural communities have the same sort of drug problems as any city or town but users have to work harder to hide their problems.

She points to the outside of van – no signwriting, no stickers.

“I live on the West Coast, people know who you are, they know what you do. They often know what you've done before you've done it. So you don't want people knowing your business.”

She leads the way to the exchange’s warehouse. Boxes of syringes fill shelf after shelf, different colours for different needle types – larger syringes for opioid users, smaller ones for P.

Meth users move to injecting when smoking it no longer gives them the high they’re after, she says.

Once the exchange’s needles went almost exclusively to opioid users.

Nowadays, it’s thought about half those that go to the North Island enter the veins of meth users, while in the South Island it’s about 15 percent.

“Are our rural communities awash with methamphetamine? I don’t know... But there is an increasing amount.”

Norman Tavave is in the dock of courtroom five waiting, shifting his weight from side to side.

Outside, his dad is struggling to find a park in the streets of Auckland’s CBD.

The judge – generously – waits, Norman’s lawyer waits, a few drink drivers wait, their own fates hanging in the balance.

Four months ago police searched the 25-year-old’s home and found two shotguns, a .22 rifle, ammunition, a stolen Subaru and five grams of meth. He told police he had the guns because he feared people may have been envious of his meth.

His father arrives and Norman’s lawyer stands. Her white hair is cut in a severe bob but when she speaks about Norman her voice is motherly.

Norman has been off meth and in Mt Eden Prison, where he worked in the laundry, for four months. He’s calmer, can maintain eye contact now and is even happy, she says.

Judge David Sharp turns to Norman, whose large frame fills the dock.

"You present today looking very different - you probably feel very different."

Norman’s lawyer hands over a letter he’s written acknowledging he has a drug problem and that he wants to do something about it.

It helps. The judge sends him to jail for 23 months, but leaves the door open to home detention if he can find a suitable place to stay.

Norman shuffles from the dock behind a security guard. He waves to his dad and the rest of his family.

Drug charges and convictions have been steadily declining over the last decade, but meth offending has bucked the trend. Annual meth convictions have nearly tripled since 2008, to the point where they now account for two out of every five drug convictions.

In a sunlit Whangarei park, Wiremu watches his two little girls, dressed in pink, clamber up the slide.

Last March he lost them to foster care when someone complained they weren't being looked after. They were right.

Wiremu had already lost his job and his house.

"I was on a benefit and I was spending $200 a week on meth. I used to lie about having food in the house for the kids.”

After 15 years on meth, the house of cards finally came crashing down.

Wiremu's hands shake a little as he lights a cigarette.

"It's the worst feeling in the world - having your kids snatched from your arms. I never felt so hurt and alone.”

Losing the kids and then the death of his mum prompted him to go to the Salvation Army for help. The move saved his life, he reckons.

"It was hard to quit: I had the shakes, I had the spews, woke up 50 times a night but I got off it. We got the kids back just before Christmas and I couldn't be happier."

His 2-year-old clutches at his knee. Dad will come and play in a minute, he says.

"We never used to do this sort of thing, go the park with kids, go to the beach – just have fun. It was all about the meth – we were just always tired and arguing about whose turn it was to get up."

Wiremu and his wife have jobs again and they're living with the children in emergency housing. Starting from scratch at 35.

Jim* pulls his last cigarette from a pocket of his muddy jeans.

“Boom!” he says, throwing his hands in the air.

He’s describing the shock of feeling a fist crunch into his nose without warning.

It’s 10.30am and he’s stopped outside the Auckland City Mission on his way from a drinking session at a friend’s place.

He’s an alcoholic but it’s methamphetamine that delivered the fist to his face.

Three days ago, his girlfriend attacked him as she plummeted from a meth high, he says.

“She punched me in the nose, nearly broke it.”

She’s lost in a cycle of selling sex to pay for meth and using meth to cope with selling sex, he says.

The punch was the latest attack in a relationship peppered with violence.

Jim is on a sickness benefit. He has lung cancer and has also lost his left kidney, he says. He lifts his T-shirt: a pink scar cuts a jarring line from his left hip up toward his sternum.

Joanne Stevenson has just got back from a walk around Auckland’s eastern bays. She grabs herself a glass of water in the kitchen. The gleaming benches are clear except for a few breakfast dishes. The lounge beyond is immaculate and the landscaped lawn recently mown.

“It’s not usually like this at all,” she says.

The phone could ring at any time, Joanne could say “yes,” and by tomorrow the floors could be littered with colourful toys and the benches covered in bottles.

Joanne fosters babies through Barnardos. Of the 15 or so babies she has cared for over the past eight years, two had been exposed to meth and she suspects many of the others had too.

Her hand flutters up to her throat.

“One baby had to have a special bottle because he had to strengthen his throat, so feeding baby would take a long time. You’d have to just be very still,” she says.

She digs through a pile of papers and pulls out one written by US experts on drug and alcohol-exposed babies. She is on a mission to find out how to give the best care to her tiny house visitors, she says.

“Meth-affected babies need a lot of sleep, they need very little stimulation, even from people holding them, people breathing next to them, colours, noise,” she says.

The phone rings. The answer phone picks up. It’s not the call - but that will be coming.

P babies

“He was malnourished, he had scabies”

When Joanne Stevenson began fostering children eight years ago, she was surprised to find herself caring for a number of very “easy babies”. They rarely cried and were great sleepers.

Her naivety didn’t last long. She discovered babies exposed to meth often behaved this way and while they could be easy to care for, their lives had been anything but.

One 6-month-old arrived covered in faeces. He had been left lying on the floor for long periods by his meth-addicted mother.

“His siblings were around 3 and 5 and they were caring for baby because mum wasn’t at home, so they were feeding him Milo. He was malnourished, he had scabies and also he was just a very, very easy, quiet baby. He didn’t cry because he knew that if he cried there was no point.”

In the newborn intensive care unit at Auckland Hospital consultant neonatal paediatrician Dr Simon Rowley says babies exposed to meth in the womb – usually along with a cocktail of other drugs and alcohol – often have sleeping and feeding issues.

“They might feed poorly and be particularly disorganised in their feeding pattern. They’re difficult to rouse and they’re also difficult to settle and their behaviours are just disorganised and chaotic.”

But if those are the only problems, the babies are in comparatively good shape. Taking methamphetamine while pregnant can cause miscarriage, placental abruption (where the placenta pulls away from the uterus) and lower birth weight, Dr Rowley says. Some studies suggest babies can also be born with smaller heads and congenital malformations, including gastroschisis, where the intestines sit outside of the baby’s body.

If babies exposed to meth are born healthy they can still end up with medical problems because of the care – or lack of care – addicts are capable of providing, he says.

Joanne Stevenson can attest to that. Just ask her what happened to that malnourished 6-month-old.

“Once he knew that he was getting a bottle regularly you could just see him transform in front of your eyes. When the social workers brought him he looked very frail and by the time they picked him up, they actually walked right past him – they didn’t realise he was the same baby.”

Carl* is perched at the breakfast bar beside a neat stack of books: Total Recovery, Addictions, The Bible.

Beneath his baggy jeans is an electronic ankle bracelet shackling him to the small Nelson flat he shares with his mum, Stacey*.

Since trying meth at 17, Carl, now 27, has cooked the drug and been in and out of jail for burglary, theft and violent crimes.

He was inside when his brother was fatally shot in the chest at a picnic spot. He wasn’t allowed out for the funeral. Later, he broke the noses of two women in retaliation over a comment about his dead brother.

Stacey, her strawberry blonde hair shot through with grey, has had her own struggles with drugs. Not meth though. Nothing like meth.

“It’s a demonic drug, it’s the most evil drug I’ve ever come across,” she says.

“I can’t stand the person it makes my son.”

Carl removes his black cap and pushes back the hoodie as he speaks about how Stacey’s drug problems shaped his own.

“Her background came into our parenting - stuff she never dealt with."

He picks his words carefully but tears still spring to Stacey’s eyes.

In the living room, a tribe of young children tumbles over a huge brown sofa.

"I want to raise my kids different and break the cycle of dysfunction in our bloodline,” Carl says. “I have an 8-year-old son who grew up in my hardest years.”

"My biggest wish is that he stays on track, and the falling off becomes less frequent,” Stacey says.

"When he's like this he's amazing and I love him.”

Tai Fakauka is yet to have breakfast but she’s drained a plunger of coffee and is ready for the morning’s next call.

“Kia ora, thanks for calling the Alcohol Drug Helpline.”

A monitor hangs high in the corner of the office and displays rows of figures – the number of callers waiting, the number of calls taken today, the percent that have been answered within the goal time of 20 seconds (66 percent this morning).

The largest number of calls to the line, run by the National Telehealth Service, are about alcohol but after that it’s meth.

Some callers are agitated, some are crying, some are using meth every day but are still functioning and speak calmly. Some are rich, some poor, some urban dwellers, some rural. But there are similarities, Tai says.

“There’s a common theme of trauma – something has happened in their life and coincidentally they’ve met up with meth and meth has been that numbing strategy to handle the emotional, dark stuff.

“It’s so easy to get, it’s everywhere,” Tai says.

The numbers on the monitor tick over.

Read more about the increasing availability and decreasing cost of meth

Before Carla* starts her shift at the agency in a few hours she will take herself off to a clean, quiet, private space, pull a tourniquet tight around her arm, swab the top side of her left hand with antiseptic and shoot meth into her vein.

She’s 45. She’s been a sex worker since she was 18 and she’s used meth intravenously almost daily for 20 years.

She sits at a wooden picnic table outside the New Zealand Prostitutes’ Collective branch she visits each week to collect clean needles. In her left hand she holds a roll-your-own cigarette. In her right is a blue Bic lighter. She uses the lighter like punctuation, banging it on the table to emphasise each syllable.

“Ne-ver-use-the-same-site-twice. Al-ways-use-a-new-nee-dle.”

Tiny scars run over her hands where veins have been damaged. Thick foundation almost hides the broken skin on her nose and cheeks.

She blasts meth because it’s better for her body than smoking it, and it’s more economical, she says. It costs her $50 for the hit that will get her through a night of work.

It’s not that she couldn’t do it without the drug - she’s not addicted, she says - she just doesn’t want to stop.

“I don’t want to go to work straight. F*** that. I gotta deal with men. Men piss me off. So to deal with them and to be sparkly-eyed and bright and bubbly, it costs me $50.”

She slams the lighter into the table.

CARLA

“I’ll do this till the day I die”

Carla’s never not used meth. Well, not since it came to New Zealand about 20 years ago, anyway.

Back then, it was brown, like heroin.

“It actually looked like brown sugar. I was sitting at home one day and a friend turned up with a tray of it. It was smoked - we didn’t know too much about it back then. Pipes weren’t around, so it was smoked on tinfoil.”

In 1999, she visited the US and found people smoking meth with glass pipes. She gave it a go, liked it, and bought an ounce for US$280.

“It was the size of a tennis ball, and solid. For three weeks I had about 18 hours’ sleep. In the end I gave it away.”

At first, it wasn’t gangs cooking meth in New Zealand, Carla says. They didn’t know how to.

Her friends did though and they taught her. They all lived in the bush, up a dirt road. They cooked the meth and sold it to gangs in Wellington. They never sold to local people. “Because local people talk. And that’s how you get caught.”

Sometimes she feels bad about supplying the drug that’s caused so much damage.

“I saw families, I saw people lose everything within a year, and I felt like, ‘Oh my god. I did that,’ because we introduced them to it.

“But then, if you couldn’t handle it... You gotta use the drug, not let the drug use you. I’m strong. I’ve always been strong with it.”

Carla hasn’t smoked meth for a long time. “I don’t like smoking it. I don’t like what it does to my head,” she says.

It was when her friends first started cooking that she began injecting.

“I hated the fact that on the pipe everyone would sit around for five, six, seven hours and just talk about shit. That’s why I blasted. I started having a hit in the morning and that would take me through all day and I would go to sleep at midnight.”

Nowadays she only uses it for one reason: work. Sex work. Meth keeps her awake. It makes her eyes sparkle, keeps her bright and bubbly, enables her to deal with the men who are her clients. She doesn’t really like them otherwise, she says.

If she decided to stop one day, could she?

“Yep. But I don’t want to. Why? I’ll do this till the day I die.”

She doesn’t need to stop, she says. She doesn’t have a problem, she says.

“I could go weeks, months without it. But if I want to have it, I’ll have it. If I don’t, I don’t. I don’t wake up in the morning and feel like I need it.”

Some people drink wine every day, she says. “I know people that do that. Two bottles. I think what I do is probably way less harm on my system.”

But she knows she’s living on a knife edge. She calls meth the devil’s drug. If you are not strong, she says, you will fall. Hard.

While the amount of precursor material being seized by police and Customs has dropped, from 874kg in 2008 to 576kg in 2017, the amount of finished methamphetamine seized has dramatically increased, from 19kg in 2008 to 404kg in 2017.

Brendon Warne is where he is every Friday: sitting at a fold-out table on the main street of Dannevirke, a cap pulled backwards on his head, his anti-P message stamped in bright yellow on his T-shirt.

A packet of Cameo Cremes lies open on the table and a sticky tape holder stops a pile of anti-meth stickers from flying away on the brisk morning breeze.

A man in stained white gumboots wanders past. The pair grip hands in greeting and Brendon sticks an anti-meth sticker to the man's shirt.

“We’ve had over 200 people through here in six months and two others have graduated rehab,” Brendon says, the corners of his mouth turning up with pride.

A gang president and meth addict turned ordained minister, Brendon founded the Anti-P Ministry to get ex-addicts helping those still struggling with the drug.

"People can trust me, they know I can help them with whatever they go through. I've been through the psychotic episodes, I've been charged with methamphetamine possession," he says.

The Ministry has trained two people in social work – one, Fiona Watson, sits at the table with Brendon, alongside Brendon’s brother, a grandmother, and Brendon’s child, who plays on his tablet.

“He’s always trying to give people my T-shirts,” Brendon laughs about his son.

They’d like to get off the pavement and find a home for the weekly drop-in, says Fiona, but the community halls aren’t keen to give space to a group involved with meth users.

“I’m quite amazed because there’s quite a lot of empty buildings, we’ve approached a few people who say they can’t do that.

“It’s only two hours a week for goodness sake!”

Read more about the Anti-P Ministry's work in Dannevirke

Bex Mabley smiles cautiously trying not to reveal too many of her teeth. Or what's left of them.

Those that haven't been kicked or punched out by her former abusive meth-addicted partner are broken and decayed after a decade of almost daily meth use.

"He would give me the option, 'You've got 30 minutes to get me high or you're getting a hiding," she says.

Right now she’s on her lunch break from rehab, sitting in a shady park to escape the Hawke’s Bay heat.

Bex started using methamphetamine at 17 but it was when she began injecting that life tilted into chaos.

She lost her three kids and so much weight that her bones rubbed up against her skin. Most of her family lost their patience.

The beginning of the end came when she tried to run from her abusive partner and her addiction.

She headed to Auckland but within a week she was using again, stealing and defrauding to fund her habit.

Her bid for freedom ended in a jail cell. She went into withdrawal and slept for the first two of her eight months inside, emerging to find letters and pictures from her children and a new determination to stay clean.

"For a long time I convinced myself that I didn't want that fairy tale ending. But I do,” she says.

The afternoon rehab session is about to start and Bex is eager to be on time.

She gets up, squinting in the bright sun as she heads across the park.

*Names have been changed.

Data sourced from the Ministry of Justice, district health boards, Customs and police

Edited by Veronica Schmidt

Reporting by Veronica Schmidt, Anusha Bradley, Kate Newton, Lois Williams, Susan Strongman, Teresa Cowie, Tim Brown, Edward Gay, Sally Murphy, Andrew McRae, Charlie Dreaver, Alex Behan, Conan Young.

Videography and photography by Dan Cook, Claire Eastham-Farrelly, Rebekah Parsons-King, Anusha Bradley, Tim Brown, Conan Young and Charlie Anderson.

Art direction and design by Dave Wright

Development by Van Veñegas

Data Visualisation by Harkanwal Singh

Where to get help:

Alcohol Drug Helpline 0800 787 797

Lifeline: 0800 543 354

Suicide Crisis Helpline: 0508 828 865 / 0508 TAUTOKO (24/7)